Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, a reminder that logic often depends on your frame of reference…

A STUDY IN CONTRASTS

On Friday, the Guardian interviewed Rijksmuseum director Taco Dibbits to gain insight into the long-planned, just-begun (as of my writing) restoration of The Night Watch (1642), arguably Rembrandt’s most celebrated painting. The pomp and circumstance surrounding the job offers valuable insight into the art market—but only if it’s considered in the context of the drastically different standards informing condition issues in another specialty market.

As background, the Rijksmuseum announced the restoration last fall. The Night Watch, a group portrait of Amsterdam’s civic guard in motion, has been exhibited as its main attraction since 1808. Recent estimates suggest the work is viewed by about 2.2 million visitors annually. Yet as is so often the case, stardom has wrought its fair share of damage, too.

The Night Watch has been assaulted three times in the last 120 years. According to Time, the first incident took place in the early 1900s, when an “an unemployed navy cook attempted to slash it with a knife—for no apparent reason.” Then, in 1975, a Dutch teacher cut several zig-zags into the canvas, allegedly as revenge for being told he’d arrived a few minutes too late to enter the museum the night before. And most recently, in 1990, a German man with a mental illness and a track record of targeting artworks doused the painting with acid, although museum staff were able to stop the corrosion before it ate anything more than part of the varnish layer.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, Known as the ‘Night Watch’, (1642). On loan from the City of Amsterdam.

While contained restorations were performed after the last two of these episodes—the unemployed navy cook somehow failed to actually penetrate the painting with his blade of choice, which probably says something about why he was out of work in the first place—major treatment has been a long time coming for The Night Watch. What began Sunday night certainly fits that description.

The undertaking begins with an estimated 10-month analysis and documentation of the painting’s underlayers using advanced technology. Informed by the new lessons learned about its makeup, the actual restoration will follow, with specialists working inside a custom-designed glass enclosure that will put the process on view IRL for museum visitors and online via live-stream for the rest of the world. Museum officials anticipate the undertaking will require multiple years and millions of euros to complete.

The art world can justifiably apply a whole host of adjectives to “Operation Night Watch,” as it’s been playfully dubbed. “Intricate,” “heartening,” and “impressive” are three that spring to mind for me. But based on what I just recently learned, if a similar process were to be undertaken for a revered object in another high-end collectibles market, here are three very different adjectives that would justifiably apply.

“Appalling.”

“Sacrilegious.”

“Criminal.”

That other high-end collectibles market, you ask? The one for… baseball cards.

William Klein, Baseball Cards (1955). Photo: artnet.

STANDARD DEVIATION

Now, there are numerous similarities between the markets for art and baseball cards. The most important is that both would be classified by economists as positional goods: objects that can only be valued in relation to other objects of their own type because they lack any objective, intrinsic worth. We can only appraise a Helen Frankenthaler painting by comparing it to prices realized for other Abstract Expressionist works of the same period, and we can only appraise a 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle card by comparing it to prices realized for other golden-age cards commemorating Mantle’s Hall of Fame contemporaries.

But as noted in a recent New York Times piece by Bill Sullivan, the two markets diverge violently when it comes to the concept of restoration. To be clear, baseball cards in pristine condition are still worth more—often, much more—than, say, cards that look like they were rescued from the depths of an Old West spittoon. The difference, however, is that restoration actually lowers the value of a vintage baseball card, even if the treatment consists of nothing more than removing stains or trimming a few millimeters from the edges to eliminate wear.

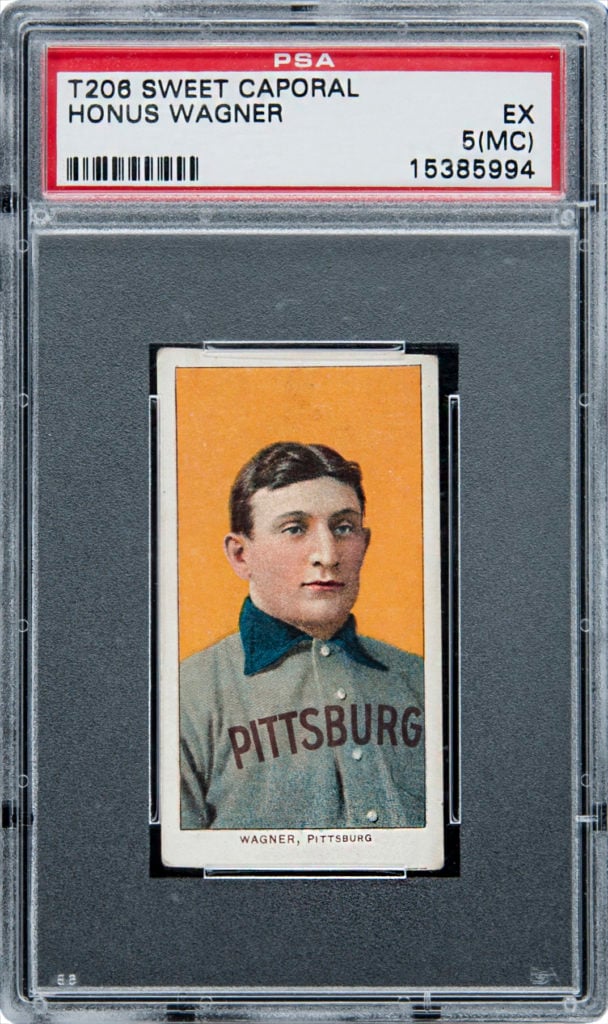

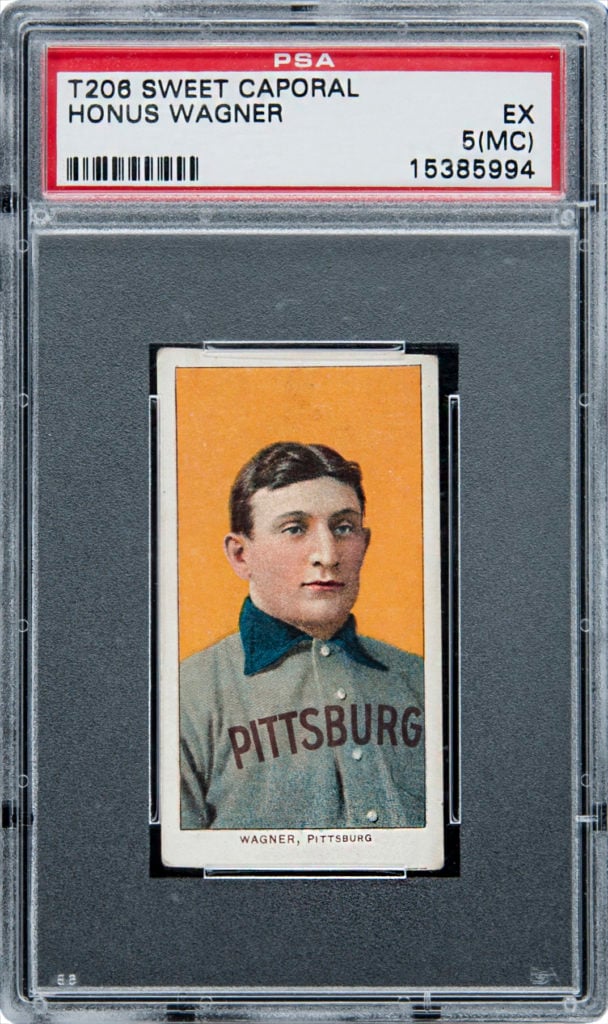

In fact, card sellers can be walloped by heavy penalties if they undertake restorations without disclosing them to potential buyers. As proof, Sullivan cites the case of Bill Mastro, who he calls “the king of card sales” throughout the 1980s. In 2013, Mastro was sentenced to up to five years in federal prison after copping to multiple instances of memorabilia malfeasance, headlined by the admission that he secretly shaved the edges of what was then the highest-priced baseball card ever: a 1909 T206 Honus Wagner, which Mastro had sold six years earlier for $2.8 million.

This T206 Honus Wagner (which is not the one fraudulently trimmed by Bill Mastro) set a new world record price for a baseball card, selling for $3.12 million at Goldin Auctions, in 2016. Photo courtesy of Goldin Auctions.

Let’s just take a moment to absorb this, shall we? The card in question was the genuine article, not a forgery. But the standards of the market dictated that skillfully trimming the real thing a nearly imperceptible amount to make it look better qualified as a con job deserving of prison time. In comparison, the years-long restoration of one of the world’s most famous paintings is now being live-streamed like a high-profile spectator sport—and celebrated as a gift to art lovers everywhere. (Furthermore, while the extensive restoration of Salvator Mundi brought out its fair share of critics and doubters, few would argue its pristine surface did not play a role in helping the painting become the most expensive ever sold at auction.)

The point is this: specialty markets have a tendency to create their own rules, and those rules don’t always make a whole hell of a lot of sense to anyone outside their boundaries. Nevertheless, they also tend to be extremely durable among the initiated.

Case in point: just as the baseball-card market has spent decades railing against restoration (which seemed absurd to me at first), the art market has spent decades prioritizing profits over careful “placement” of artists’ works. If you think our rules make more sense than their rules, try explaining to someone outside the art world why a gallery would prefer to sell a painting to the Museum of Modern Art for $75,000 instead of to an unfamiliar billionaire for $250,000.

Trust me, it’s hilarious. There is a good chance they will either look at you like a shaman describing your travels in the spirit realm, or they will become so convinced that you’re lying to them that they will try to fight you.

So the takeaway here is that, if your livelihood depends on selling a positional good like art or baseball cards, you might as well get intimately familiar with the conventions of your particular niche. Chances are, they’re not going anywhere. And if they do, it will only be because contrarian thinkers dismantled them from the inside. As the old saying goes, learn the rules well so you can break them effectively.

[The Guardian | The New York Times]

That’s all for this week. One programming note: the Gray Market will be on hiatus for at least the next week, and potentially the next two. It’ll be back before the calendar flips to August, though.

‘Til then, remember: beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but fair play is in the eyes of the market.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.