Art & Exhibitions

Sculptor Heide Fasnacht on the Ephemerality of Our Built Environment

Recent work includes a sinkhole in Brooklyn's Socrates Sculpture Park.

Recent work includes a sinkhole in Brooklyn's Socrates Sculpture Park.

Born and raised in New York, Heide Fasnacht has been witness to many changes the city has undergone in the past years. From natural disasters, such as Hurricane Sandy, to the September 11 attacks, shifting landscapes and cultures are reflected in both the subject matter and execution of her works. An excellent example can be found in Fasnacht’s current exhibition, entitled “Suspect Terrain,” in Socrates Sculpture Park. On view until August 30, the work depicts a sinkhole, and explores the transitional states of destruction and regrowth in our built environment.

You’ve worked in a lot of media, such as works on paper, Styrofoam, and plywood. Are there any media you still want to explore?

Currently, I am very interested in using vinyl as a material for sculpture and, in particular, ink jet prints on vinyl.

What inspires you?

For many years I’ve been interested in very unstable, ephemeral situations that change over time. I do not use sculpture to depict a concrete, fixed entity, but as something that is subject to movement. An example is my work Suspect Terrain, in Socrates Sculpture Park. I had made a piece about a sinkhole in my studio and was invited to make it on a larger scale outdoors. My interest in sinkholes was precipitated by the destruction of buildings and art through various means, such as weather, war, and iconoclasm, and I decided to start looking at the aftermath of those events.

Heide Fasnacht, Suspect Terrain (2015). Wood and paint, 7 x 50 x 45 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

If you were not an artist, what would you be doing?

I love fiction and I read a lot. My fantasy is to be a writer, but I’m really not a good writer. I’m very interested in crossover genres, such as fiction and memoir, or fiction and nonfiction. I like that the writers are working consciously in both of those categories and you can’t quite place where it belongs.

Does what you read ever influence your work?

Oh, yes. Most recently I read John McPhee, In Suspect Terrain, which is the name of my current work. The author writes about the formation of Brooklyn by the glaciers, and their journey over the site of Socrates Sculpture Park. Throughout Brooklyn, there are many areas that are broken from the glaciers. In fact, Brooklyn actually means “broken land.” Another book that has influenced me is Delirious New York by Rem Koolhaus. If you live in New York you have to read this book.

How do you title your works?

Sometimes they just come to me, sometimes they’re really painful to name, and sometimes I regret them. I think pieces title themselves, too. For example, people do not call my piece Suspect Terrain, but instead refer to it as “The Sinkhole.”

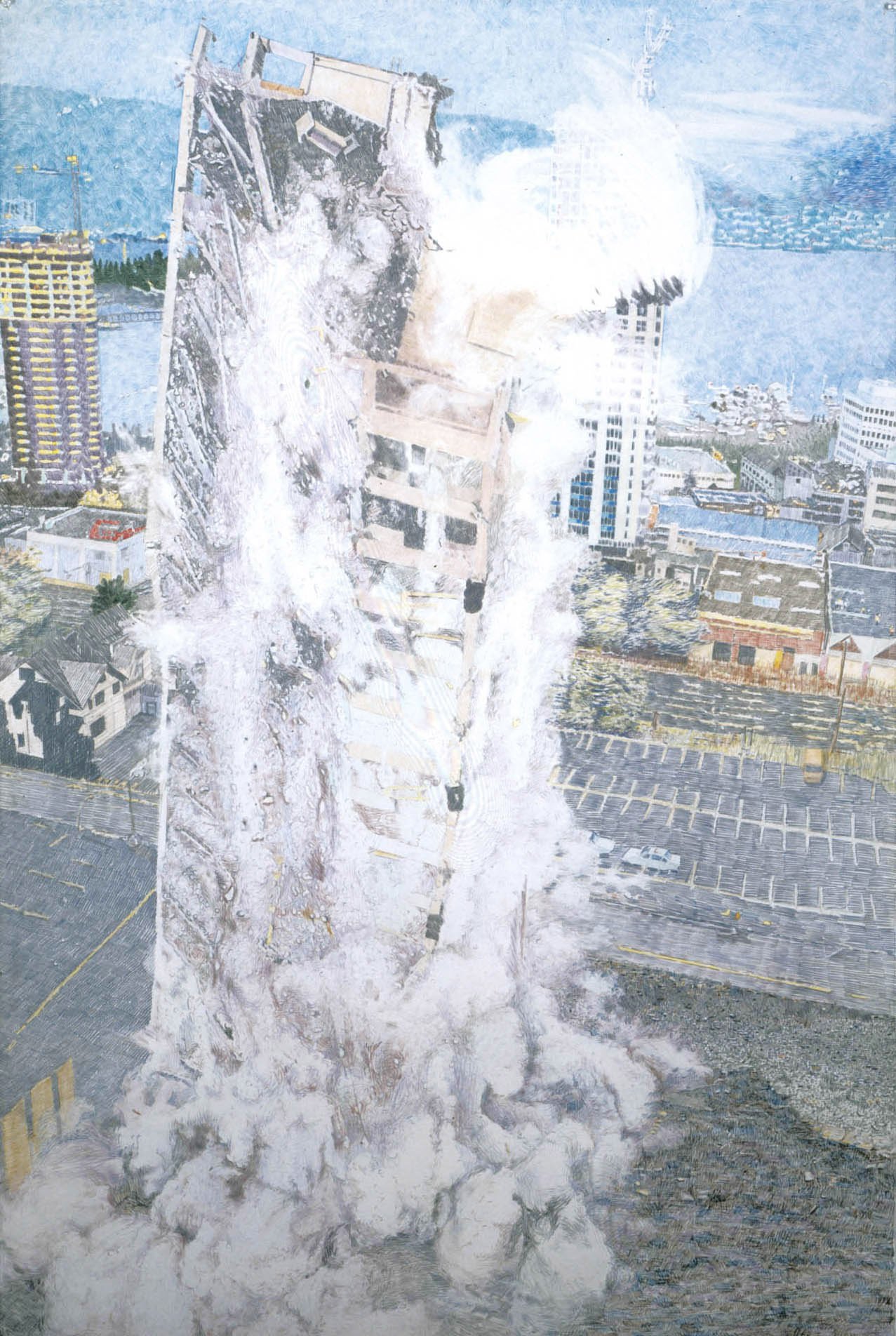

Tell us about your other piece, New Frontier, that was recently on view at Kent Fine Art.

The work is titled after the casino from which the debris was taken. Las Vegas changes very rapidly—things are built and demolished often. I am interested in shaky structures, such as the economy, cultures, and architecture, and their transformation into materials of transitional states, like collapse. If you’re looking at a pile of debris, you know that something is going to grow there. It’s cyclical, not a sad end. I’d like to continue to explore boom architecture that comes to an end and then gets rebuilt. I don’t really like Las Vegas, but I do have a morbid fascination with the city. I’m intrigued by paradox, so I like when something is both wonderful and awful at the same time.

Heide Fasnacht, New Frontier (2015). Vinyl and mixed media, 9 x 14 x 7 in.

The aftermath of the implosion of the “New Frontier” casino, Las Vegas. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Do you ever experience artist’s block?

Yes, for long periods sometimes. I had a couple of years that were really hard, but I worked anyways and made a lot of works I ended up tossing. It was actually after 9/11 that I found it difficult to create art. I couldn’t understand the explosions and it took some time to come to grips with that.

In 2001, I saw two large tanks implode in New York, and for the event, a local Italian bakery made two cakes in the shape of the structures. When I got home I hung my camera on the doorknob and forgot about it. A few weeks later, the World Trade Center blew up. I grabbed my camera and took pictures, but it took about six months before I had the nerve to develop the film. When I finally did, I thought, “Oh god, I’m going to have to look at the Trade Center,” but then there were also the two cakes.

Did people react to your works differently after 9/11?

Yes, a lot of people don’t look at the dates, so they thought I was ripping off the 9/11 event.

Heide Fasnacht, Demo (2000–2001). Polychromed Neoprene and Styrofoam, 112 x 125 x 120 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

What does an average day in the studio look like for you?

I work on and off all day, every day in my home studio. I start out with image research, or I will read something, such as Learning from Las Vegas, and usually within 15 minutes I will start working.

How do you evaluate success as an artist?

I think being able to work in the studio every day is real success. You have to think that way. There are two sides to being an artist; there is the private side and the public side, and they are always in tension with one another. We really want to be left alone more than anything, but we also don’t want to be forgotten. The private side is the side you can control, and you try to make that as rich and varied as you can. As for the public side, you can work really hard at it, but given certain demographics, artistic style changes, and changes in the economy, it can be really difficult.

How has your art evolved in relation to the art world?

I’m always trying to push my own boundaries, not the boundaries of the art world. A lot of the people pushing the boundaries aren’t necessarily interesting. I think the question of what is groundbreaking or what is new can sometimes be a very tiny increment, not necessarily a big, spectacular change. Sometimes a small variation can make you understand something much larger.

If you could own any artwork, what would it be and why?

I’d have to own a whole city. The work is called Cretto di Burri in the town of Gibellina, which was destroyed by a volcano. It’s the most incredible piece. The artist Alberto Burri left the roads empty, but used concrete to fill in where the houses would be located, so it’s the entire town. Another favorite is Medusa’s Head by Chris Burden.

If you could have dinner with anyone—living or dead, real or fictional—who would it be and why?

W.G. Sebald.

Heide Fasnacht, Three Buildings (2000–2001). Colored pencil on paper, 59 ¾ x 40 7/8 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.