Even in its revised, more carefully worded form, President Donald Trump’s executive order on immigration has been widely perceived worldwide as a “Muslim ban” by another name, more a way of keeping a xenophobic campaign promise than a national security requirement. Yet while its target may be racially coded, reports have streamed in from all sorts of people of unnerving scrutiny at the border.

Consider the case of artist Aaron Gach.

As a white American and a U.S. citizen, Gach is not a candidate for racial profiling. Yet he claims that he faced unexpected and invasive 90-minute questioning by Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) while returning from an exhibition in Belgium recently (Gach published his account of what happened in a detailed Google document, as a reference point for others).

His account made it into a digest put out by the PEN America of artists and writers who have experienced newly “aggressive interrogation” at the border. But just how unusual was Gach’s experience?

artnet News contacted three separate immigration lawyers who commonly work with artists to ask. After reviewing Gach’s account of his questioning, they used words like “weird,” “troubling,” and “overreaching.” The sense of unusual scrutiny, they said, was not at all in his head.

Gach’s Account

Gach was returning to San Francisco after attending the opening of the show “Artefact: The Act of Magic,” at STUK House for Dance, Image & Sound, in Leuven, Belgium. On touchdown, he found himself diverted into secondary questioning.

There, he says, he was repeatedly asked questions ranging from how to spell his name to who invited him to Belgium, whom he met while he was there, and whether he could provide their contact information. The agent often asked the same questions multiple times, even when the information they were asking for was in front of them, in writing.

Gach also claims he was asked to surrender his phone, which was taken out of his sight for several minutes. “It would be foolish to assume they didn’t download the information on the device,” said attorney Reza Mazaheri in a phone interview with artnet News.

The artist says it’s still a mystery to him why he was stopped and questioned by the agents, who would say only that the information they were requesting was in furtherance of an investigation.

Interpreting What Happened

After reading Gach’s experience, attorney Eric Shaub had some questions, which artnet News relayed to Gach: Had he traveled to the Middle East? Had he ever been detained in this way before? Does he know of any bad actors with the same name as him? Gach replied “no” to all, adding that he has no arrest record and is under no investigation that he’s aware of.

“This is very unusual,” concluded Shaub in a phone interview.

Immigration lawyer Pierre Georges Bonnefil was startled after reading Gach’s account, which included a long list of the questions asked to the artist. “The sheer number of questions they asked is outstanding to me,” he said in a phone interview. “The questions were just amazing.”

Bonnefil described the lines of questioning as “invasive.”

While declining to comment on Gach’s experience, a public affairs officer for Customs and Border Patrol said that agents “strive to treat all people arriving in the country with dignity and respect” and pointed out that “unless exempt by diplomatic status, all persons entering the United States, including U.S. citizens, are subject to examination and search by CBP officers.”

Mazaheri, the immigration lawyer, had a different interpretation. “It’s not about security,” he said. “It’s about intimidation and just gathering information on people.”

Possible Explanations

Might the authorities have stopped him because he was in Belgium, site of a terrorist attack last year that killed 31 and injured 300, I asked Gach?

“That’s by far the most interesting question but also the most problematic, and ultimately it’s all supposition,” Gach said. “There’s a problem with asking the person who was singled out why he was singled out—less so for me, more so for others in more vulnerable populations.”

A more disturbing possibility is that Gach’s art practice, which has been critical of law enforcement and US policy in the past, made him a target.

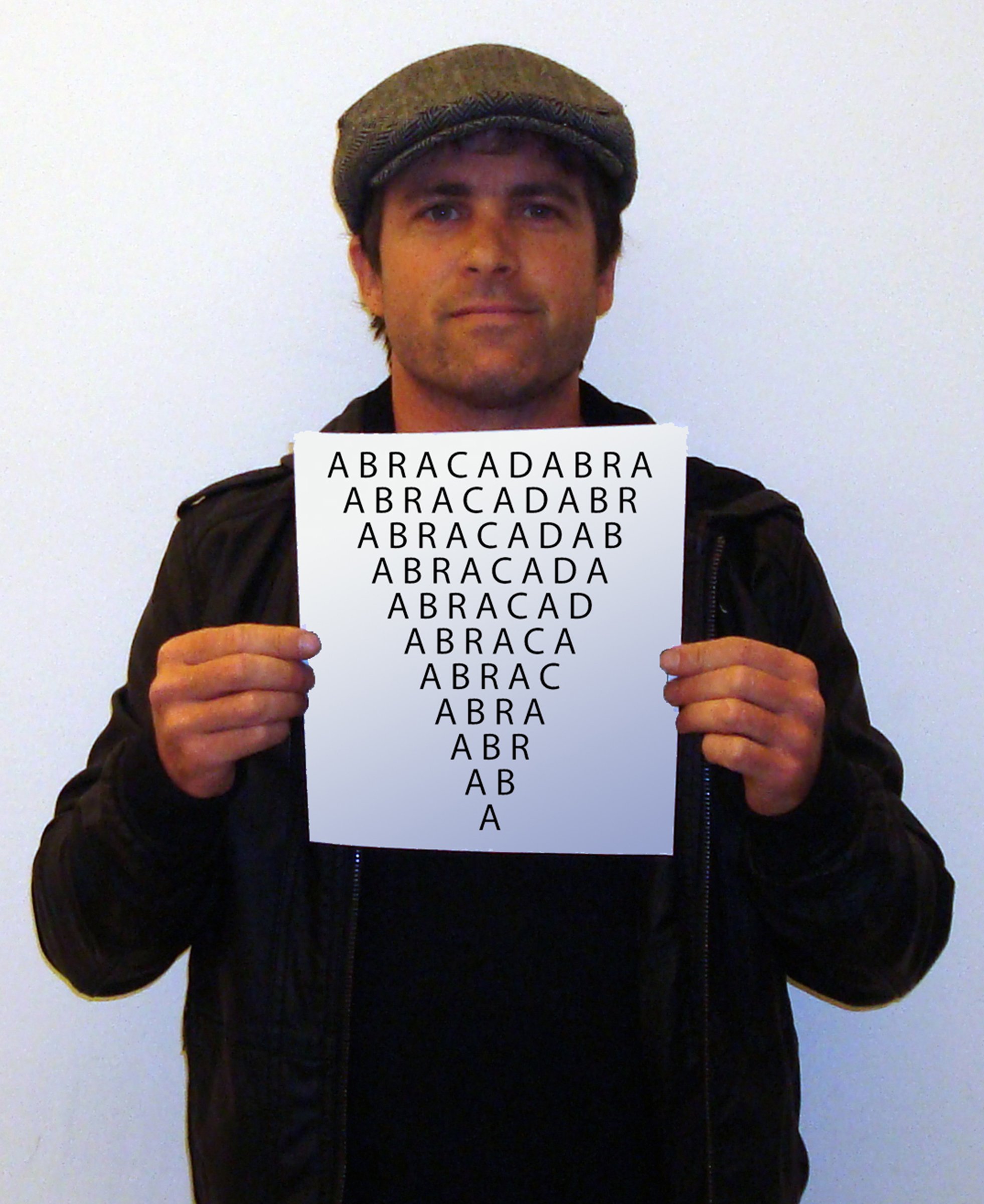

Center for Tactical Magic, Witches Cradles (2009). Courtesy Aaron Gach.

Gach operates under the name the Center for Tactical Magic. His work often consists of détournements like the Tactical Ice Cream Unit, an ice cream truck that harbors surveillance systems that might allow citizens to monitor police activities. It also can provide refreshments and supplies for protests.

Another piece, dubbed Bank Heist Contest, offered a cash reward for the best scenario on how to rob a bank as a form of social commentary: “As many people battle rising unemployment, increasing food costs, exorbitant health care fees, and bank foreclosures, the ‘get rich quick’ narrative comes head-to-head with the ‘make ends meet’ social conditions that have cultivated the legendary heists of the past.”

Gach pointed out that he was included in the 2004–05 show “The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere,” at MASS MoCA, in North Adams, Massachusetts. Also in that show was Critical Art Ensemble, whose co-founder, Steve Kurtz, was then under investigation on suspicion of bioterrorism because of some biological specimens he was cultivating in his home as part of an artwork. (A grand jury refused to bring charges.)

“Federal agents showed up at the opening, and probably every artist in that show was scrutinized,” Gach said. “It would be naïve to think the authorities just throw those lists away. Is that the one they used to identify me coming off the flight? If it is, if this is a conscious attack on anti-establishment artists, it’s a very real problem.”

Considering that his nom d’artiste includes the word “magic,” I jokingly asked whether CBP’s questioning constituted a literal witch hunt. Ironies abound, he pointed out: one of the works included in the Brussels show, Witches Cradles (2009), actually does reference the history of witch hunts.

CBP agents have total discretion, all three lawyers pointed out, and don’t have to reveal their reasons for stopping travelers—not even to their supervisors, according to Mazaheri.

That is part of the reason, Gach says, that he felt he should make his experience public. “If their power is in secrecy, then mine is in visibility.”

Preparing for the Worst

Gach and the immigration attorneys contacted by artnet News outlined some suggestions as to how both American citizens and visa holders can minimize their troubles when dealing with CBP agents—though all, including Gach himself, acknowledged that he was treated with a politeness that non-citizens and people of color might not be treated, and admitted that their suggestions only go so far.

“You should really dress up for travel,” said Shaub, especially if you’re not a citizen. “If you look serious, if you’re in a suit, it helps. It just does. If your visa says you’re an art dealer traveling to an art fair, don’t wear sweatpants on the plane.”

“If you don’t need to bring it with you, don’t bring it with you,” said Bonnefil, especially in terms of electronic devices. “If you don’t have it in your hands, they can’t ask you to turn it over. Have nothing with you that could open any doors an agent might want to go through. I’ve been told that people have FedExed computers and phones to their destination.”

As he explained in his account Gach hypothesizes that his faux-cheerful attitude, mirroring that of the Border Patrol agents, might have helped to set them at ease. He’s also accustomed to dealing with authorities, he said, and so was able to keep his cool.

Just the same, what would Gach have done differently had he known what was coming?

“I would have brought an older phone, taken out the SIM card when I landed, and scrubbed it and reset it to factory settings. Then I could have let it go if they asked for it. Because if you decline to cooperate, they can detain your phone and, along with it, everything else.”

All the lawyers agreed: Be honest. Take your time answering questions to make sure you get the answers right. If you don’t know the answer to a question, say so, because if you’re caught in what may look like a lie, you can be permanently barred from the US. Choose your words carefully. Gach’s experience of being asked the same questions repeatedly was likely, as he surmised in his account of his experience, in order to see if his answers varied.

“Is this the new world order?” asked Bonnefil. “I don’t know.”