Hong Kong’s new museum of visual culture, M+, has decided to exclude a number of my artistic photographs from its opening exhibition. The problem? One photo in my Study of Perspective (1995–) series shows me giving the middle finger to Beijing’s Tiananmen. Others show me doing the same to a number of other politically or culturally hallowed structures around the world; in Hong Kong, though, the “national security law” that China’s central government passed last year has ruined the local political environment almost overnight, and has left the Chinese government’s promise of “one country, two systems” as mere waste paper.

Influenced by the national security law, M+’s decision to exclude my work deviates from art collector and Swiss former ambassador to China Uli Sigg’s original intention when he decided to donate his collection (including twenty-four works by me) to the city’s spanking new museum. It seems hard to believe that my work, which originated in Tiananmen Square 26 years ago, has again become a flashpoint at a major historical turning point, and is a piquant footnote to the story of China’s political censorship of culture and art. In 1989, just six years before I raised that middle finger, government tanks and armed soldiers had invaded the square to drive out peacefully protesting students. A single contemptuous gesture by me was never a match for an armed assault, of course; but it does breathe life into a durable item of faith—that the value of art in politics cannot just be erased.

The fate of the M+ Museum that we are witnessing today brings to mind how certain other Western museums—the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Victoria & Albert Museum and Tate Modern in London—recently have rushed to cozy up to China, bowing and scraping before the great rising authoritarian power, bubbling with flattery at every turn.

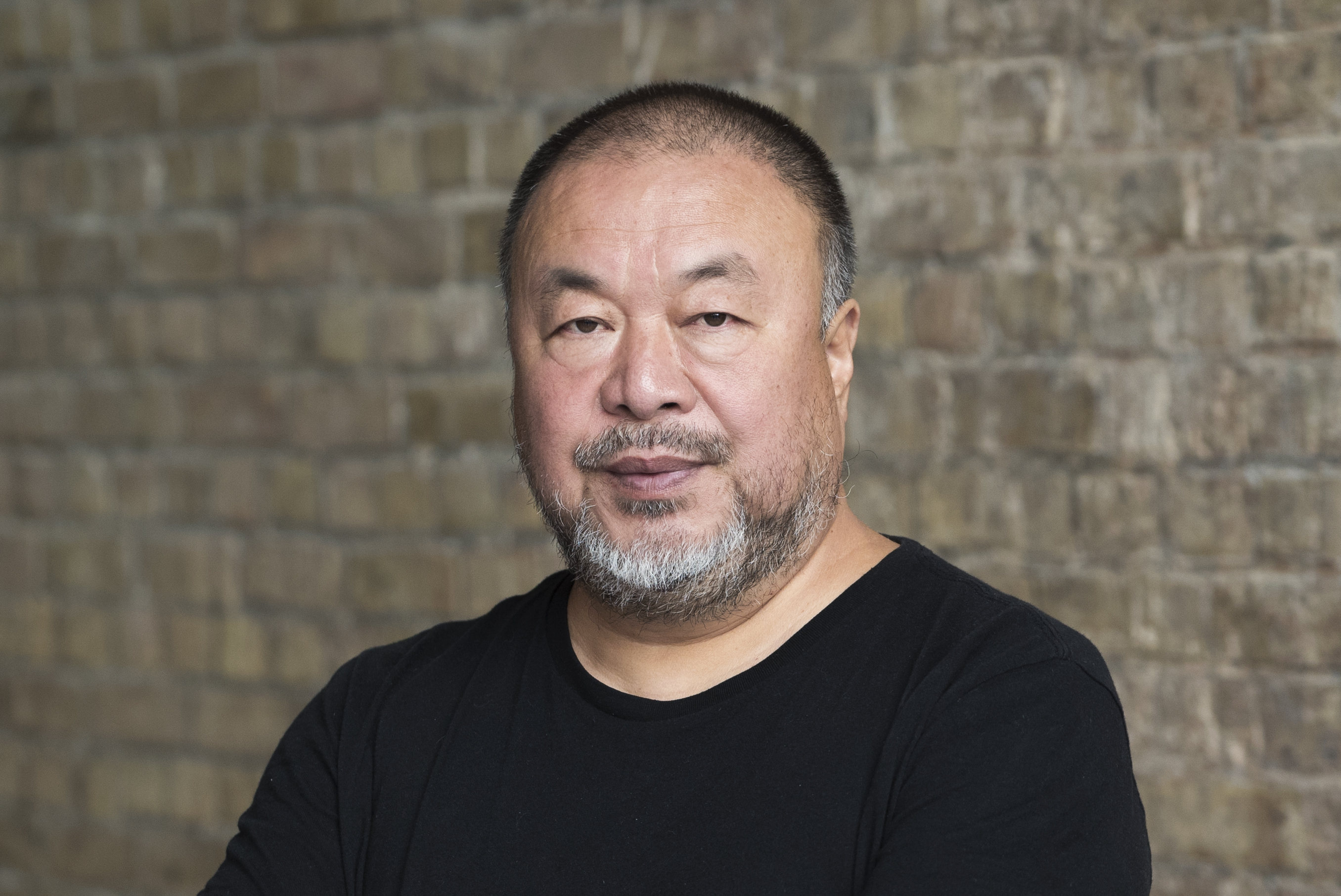

Study of Perspective (1995-). Photo courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

In spring 2021, I received a surprising notice from another kind of Western institution, Credit Suisse. The bank informed me that it was terminating my account in Switzerland. They did this, they wrote, in accordance with a new policy of closing all accounts with people who have had criminal records. They believed (or pretended to believe?) that I had been convicted of a crime in China. Just a bit of homework could have shown them that I was never formally charged, let alone convicted of a crime. When the Beijing regime detained me and smeared my name, it was only applying its normal techniques of persecuting political opponents.

So why was Credit Suisse using my “crime” as its reason to terminate my bank account? Not long ago the institution announced that it was accelerating its recruitment of employees in China. It wanted to triple their numbers in five years. At the same time, it would be seeking to take majority control of its joint ventures in the securities market and to apply for a license that would allow it to expand its business in both personal and investment banking.

Credit Suisse was already well aware of a magical strategy in China; hire “princelings”—offspring of top Communists—in order to pave the way to success in business. In 2018, the bank was obliged to pay $77 million to settle a charge by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that employment of “friends and family” of senior Chinese officials in its joint ventures violated the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

In China and elsewhere, political connections are the fuel of the economic colonialism that occupies the core of today’s surging globalization. In China’s state capitalism, high officials enjoy unchecked power and wield it in an environment totally empty of democratic supervision. As a consequence, behind the strong organizational structure of the Communist Party of China, there has arisen an immensely complex web of private interests of the highest-ranking Party families and their minions in the bureaucracies. No item of business with a foreign country can possibly go forward without involvement with this web. Shared corruption is the name of the game, and the pattern is so common as to be accepted as commonplace.

In globalization, countries or regions find themselves in relationships where each side is pursuing its own political and economic goals; at the same time, the two sides often look for people within the other side to be its agents. The Communist Party of China, in pursuit of its political ambitions and ultimately its dream to be a superpower, has been doing precisely this in the West for some time now. A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson recently declared the arrival of a happy world in which “we are inside you and you are inside us.”

The Chinese regime’s goal, in this happy world to come, is to establish that its way of doing things is normal and legitimate. Its leaders are well aware that spread of its culture will enhance the allure of its political system. What Western museums and other art institutions want is to attract Chinese financial backing. At a personal level, movers and shakers in the Western art world are also looking for political and economic advantages inside China. Every museum in China, whether run by Chinese or Westerners, wants a special relationship with that one government, that one Party, whose favor is essential for success. This marks the final triumph of cultural globalization. We think of war as invasive and bloody, but cultural invasion and war, fought with invisible gunpowder and producing odorless gore, is in fact just as cruel and unscrupulous.

Study of Perspective (1995-). Photo courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

As for Credit Suisse, it turns out to be no stranger to foul commerce, indeed it might be called an old hand at it. In 1996, Holocaust survivors and families of its victims filed a class-action lawsuit against Credit Suisse and the United Bank of Switzerland, accusing the banks of intentionally hiding assets that originally had belonged to Holocaust victims. Last year the Simon Wiesenthal Center announced the discovery in Argentina of a list of 12,000 Nazi persons or organizations that had used Credit Suisse accounts to hold purloined funds. Credit Suisse’s clientele also included IG Farben, the company that produced the Zyklon-B gas that killed 1.1 million Jews.

Switzerland has long enjoyed privileges on the world stage that derive from its reputation for neutrality. In practice, however, its banks have used “neutrality” as a label under which to nestle as they quietly side with the powerful and reap indecent benefits. It is no secret in China that high-level officials maintain covert bank accounts with Credit Suisse. That fact alone should dispel any doubts about its “neutral position.”

On June 24, 2021, the management of Credit Suisse called to inform us of their decision to close our bank account as soon as possible, explicitly stating a recent interview I did with the Swiss daily 20-Minuten as the reason. This interview, in which I criticized the Swiss people for voting in ever more anti-immigrant policies, has had repercussions across the social spectrum in Switzerland. Ex-colonel and FDP member Roger E. Schärer summarized the response in a follow-up interview with the paper: “He must not defame Switzerland so much, as the country showed him so much hospitality,” he said. “Here he finds all the freedom that was denied him in China.”

According to the news article, Schärer believes my testimony constitutes a criminal offense, and wants to file a criminal complaint against me for violating Switzerland’s Rassismusstrafnorm, an anti-racism law, unless I apologize.

The bank account at issue here is that of my Fart Foundation, which I started 2016 as a way to promote free speech. The foundation has recently supported the creation and distribution of a number of documentary films on China. One looked at the outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan, and another on how the people of Hong Kong rose in unison to resist an extradition law imposed by Beijing. That I have won a bit part in the “China Dream” of certain giant multinational corporations and their associated cultural predators makes me feel… well… honored!

Ai Weiwei is a Chinese conceptual artist, sculptor, and curator. This article has been translated by Perry Link.