THE DAILY PIC (#1585): “Dadaglobe Reconstructed” is precisely the kind of show that the Museum of Modern Art should be doing, and very often has done of late. Memories of “Bjork” have pretty much been erased by an absurdly full roster of utterly unpandering projects.

For “Dadaglobe,” curators have labored to unearth a vast trove of material once intended for what was supposed to have been the ultimate anthology of the Dada movement. The book was planned in detail by the Romanian avant-gardist Tristan Tzara, in Paris around 1921, but a lack of funds torpedoed it late in the process. All that remains are Tzara’s detailed records and the art works themselves that he’d meant to include, which MoMA has tracked down in surprisingly large numbers.

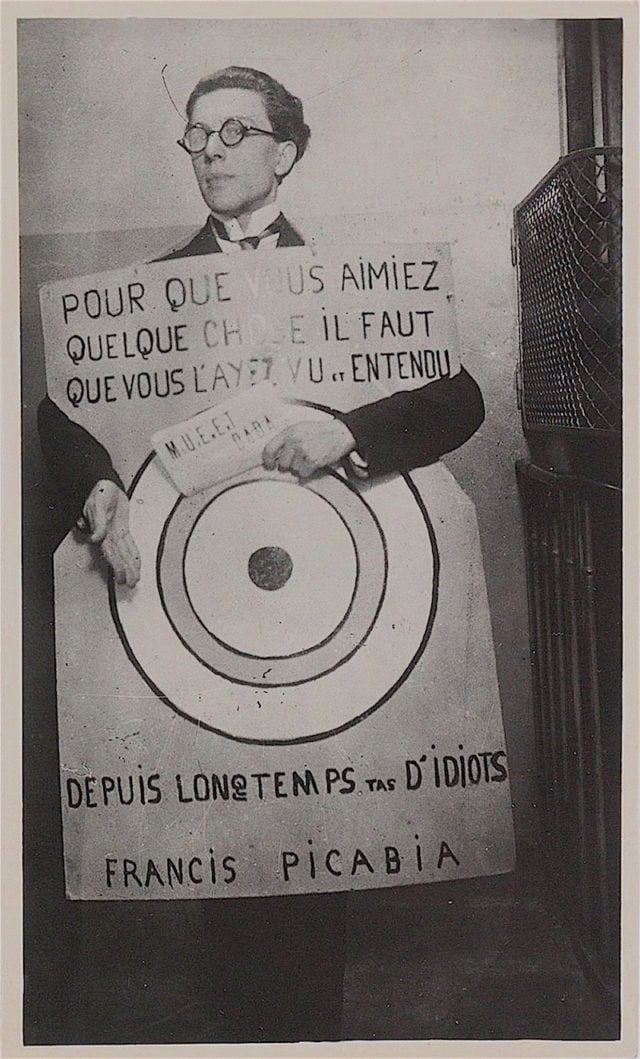

Today’s Pic is one of my favorite objects from the Tzara project, and from the MoMA show, because it does such a perfect job of summing up modern art’s love of the new, and its disdain for those who resist it. An unknown photographer has captured a dandified André Breton, not long before he helped found the Surrealist movement, at the great Dada festival in Paris in 1920. For the occasion, Breton has put on a placard designed by Francis Picabia, bearing a target-like abstraction and the words “For you to like something, you have to have already seen and heard it for ages, you bunch of morons.”

Among other things, the placard’s concentric circles make an important point that we’ve lost sight of: Abstraction, in its first years, always came with an edge of Dada absurdity to it – and maybe still ought to, if it’s to keep its original heft. Jasper Johns, another target-maker, knew this; Kenneth Noland should have. Perhaps the utter sobriety of early pro-abstract manifestos was meant to counteract any remaining odor of Dada.

I can’t help feeling that Breton is quite literally and deliberately making himself a target of jokes, with the text that he bears as the disdainful rebuttal of a voiceless martyr. (The sacrificial effect is helped by the fact that he has centered the target on his gonads.)

Breton’s silence makes sense of another element in the photo, and in Tzara’s entire book project, that I’m not sure has been much noticed.

He is holding a copy of the very letter that Tzara sent out to solicit contributions to his Dadaglobe anthology. The sheet bears a carefully designed letterhead that reads MoUvEmEnT DADA, with the alternating large-and-small type that I’ve echoed here. The thing is, for any native French speaker who looks at this photo, or even at the Dada letterhead itself, the large capitals, along with the disappearingly small letters between them, can only make that mouvement read as muet – “silent” or “mute.”

Dada was a noisy movement, for sure, and its artists enjoyed making a ruckus. But for all its deliberate absurdity, it had a space of focus and concentration at its core – as witnessed by the close-mouthed withdrawal of Breton in this portrait.

Dada pretended to be all about anti-art, but its artists knew perfectly well that in the process they were engaged in making great art, in the same lineage as Leonardo and Rembrandt and other makers of the telling and silent tableau.

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.