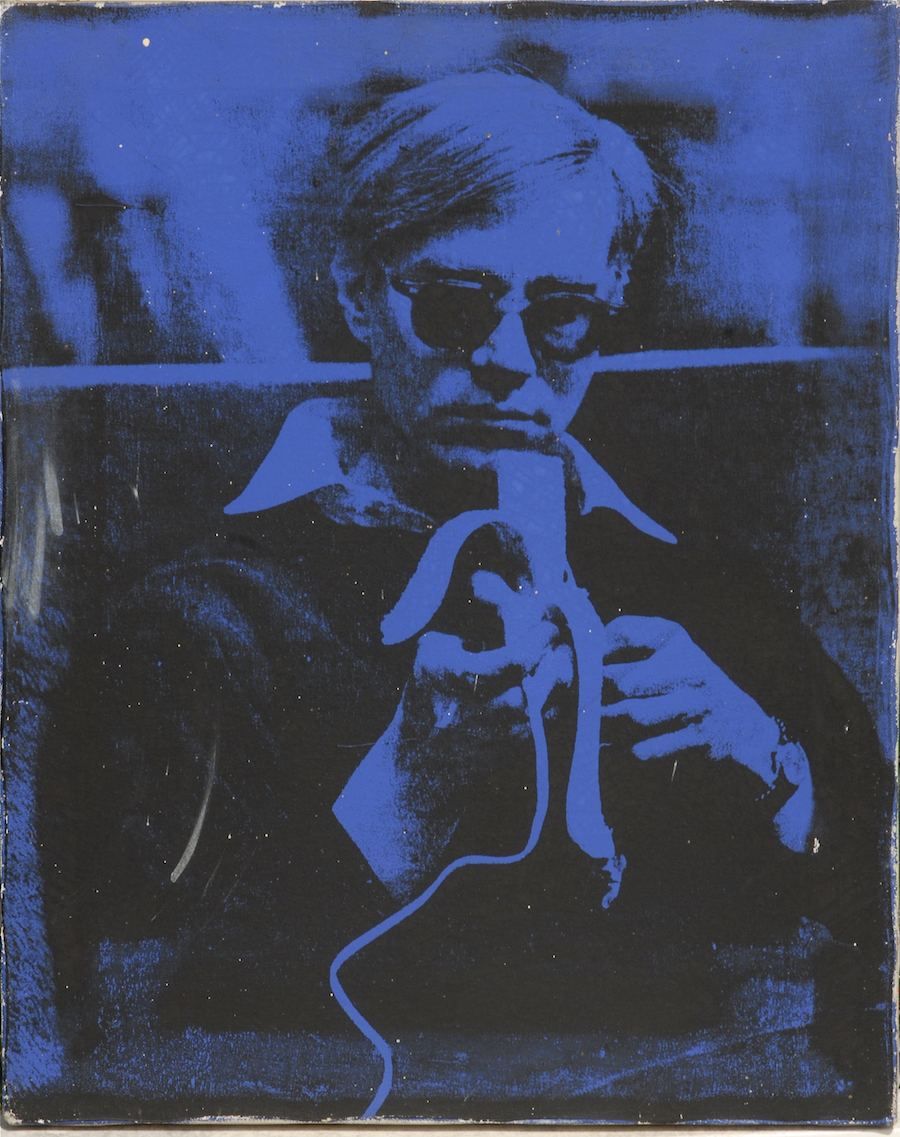

THE DAILY PIC (#1607): Tomorrow would be Andy Warhol’s 88th birthday, if only he were still alive. In honor of the anniversary, I’m posting this striking self-portrait of Warhol that is not by him – the kind of paradox that is at the heart of all his best art. Produced early in 1965, it is almost utterly unknown but also deeply illuminating about what he was all about as an artist.

This image counts as a self-portrait of the artist because he composed himself for the image and pressed the camera’s shutter, at long distance via the bulb release he’s got clutched in his hand. On an unlikely assignment for the conservative Saturday Evening Post, the writer Roger Vaughan and photographer Larry Fried had shown up at The Factory to gather material for a profile and to take Warhol’s picture, with the idea that the image would then be silkscreened and “Warholized” for play in the magazine.

They came up with the idea of getting the artist to take his own portrait with their camera, and Warhol jumped at the chance, shooting roll after roll of his own face. He was fascinated, Vaughan told me, by the device that made it possible: “Wouldn’t this be fantastic? You could take a picture of your own death,” Warhol said. (I guarantee he was only pretending to be new to the remote shutter release: He’d been close friends with a number of star photographers in the 1950s and had been taking his own photos since he was a kid – he would have known all the standard photo equipment.)

After the shoot, however, when it came time to make the silkscreen, Warhol demanded a full $5,000 to do it – an impossibly vast sum for a magazine image at the time. The Post’s editors promptly killed the story, no doubt with some relief. Warhol, the gay avant-gardist (notice his trademark banana) wasn’t exactly admired by their mainstream readers or owners; he may have returned the compliment by trying to bust the magazine’s budget.

Vaughan wasn’t quite ready to abandon his project, however. He sold his profile to the Herald Tribune’s Sunday magazine, and he had Warhol’s “self-portrait” photo turned into a high-contrast, Warhol-style serigraphy screen, which he himself printed “just for fun,” he told me, onto a series of canvases painted red, yellow and blue – one of which, shown in today’s Pic, has lived in his home ever since, sometimes out on the porch. I’ve tracked down a few others that survived when an employee at the Saturday Evening Post picked them out of the trash after a spring cleaning there. (One has always lived in a bathroom – “and it still looks great,” the owner told me.)

There’s no doubt that the object owned by Vaughan is not by Warhol, in the sense used by connoisseurs and the art market: Its back was in fact stamped “DENIED” by the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board when that body still existed, and it is most definitely not in the catalogue raisonné of his work. But I believe that the gesture involved in making the piece is totally Warholian – part of his lifelong and very deliberate performance as an artist, a self-fashioning that could never be contained within the covers of any catalog or sold-off at auction.

Warhol chose to take his own picture knowing perfectly well it would cause confusion about what counted as a Warhol self-portrait, of which he’d just completed a series. He even chose to leave clear evidence that he had shot the picture himself, in the form of a bulb release he could have easily kept out of the frame.

Warhol, well trained in the tricks and deceptions of radical modern art, reveled in disturbing our sense of what genre a picture belonged to (portrait or self-portrait; commercial or fine art) and who its true author might be (since his college days, the vast majority of his works had begun as photos by someone else.) The very idea of dubbing his studio a “factory” – which it never actually was – invoked the idea that the artist’s hand or even presence might not be involved in the making of a piece. Within months of the Vaughan (self)-portrait, Warhol happily lent the screen he’d used for a well-known flower painting to the appropriation artist Elaine Sturtevant, knowing perfectly well that, with his help, she was attacking conventional notions of authorship.

Vaughan’s picture is certainly a weapon in that attack. Though clearly not an art work by Andy Warhol, it was a great prop in his act as an artist. (Image courtesy Roger Vaughan)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.