“Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World,” a retrospective of Durham’s work that I curated for the Hammer Museum, has generated a great deal of criticism in recent weeks since opening in Minneapolis at the Walker Art Center.

The criticism, first voiced in an open letter to Indian Country, touches on important issues related to identity and tribal enrollment—indeed, these issues are taken up by the artist himself in some of his early works. Yet, a great deal of context has been left out of what has been written thus far, while some aspects of Durham’s art and the work that went into producing “At the Center of the World” have been mischaracterized or misrepresented. In the spirit of open dialogue, it is important to offer some alternative perspectives and to set the record straight on specific claims.

Durham as the American Indian Representative

First, I’d like to clarify that the Hammer Museum’s decision to mount a retrospective of Durham’s work is based on the opinion that he is one of the most important American artists of his generation. Our intention was never to position him exclusively as a Native artist, since Durham has long been opposed to such categories for artists.

To suggest that Durham has positioned “himself as the representative of all things American Indian,” as the letter in Indian Country Today reads, is to deliberately misinterpret, or egregiously misunderstand, a fundamental premise of his work.

He is not “representing” Indigenous culture in his works, but investigating how American Indian history and culture have been misrepresented by others. A number of works from the 1980s deliberately set out to dismantle stereotypes of American Indians that have been widely accepted and disseminated in American popular culture.

As Durham stated in a 2011 interview, “I’m accused, constantly, of making art about my own identity. I never have. I make art about the settler’s identity when I make political art. It’s not about my identity, it’s about the Americans’ identity.”1

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World (2017) by Anne Ellegood. Courtesy of Prestel Books.

Moreover, given Durham’s staunch resistance to categorization, he is ideologically opposed to the very notion of being the representative of anything. He has said repeatedly since the beginning of his career that he does not consider himself to be a “Native artist.” He could not be more clear on this point; he stated in 1991, “I am not an ‘Indian artist,’ in any sense. I am Cherokee but my work is simply contemporary art. My work does not speak for, about, or even to Indian people.”2

Durham has called into question the category of “Native artist” on the grounds that artists should not be put into groups based on their race, ethnicity, or gender, as it often leads to the further marginalization of those artists and over-determines the reading of their work. He has long argued that Native artists should be free to make whatever work they choose and their work interpreted and discussed within the discourses of contemporary art practice.

The Context for Durham’s Art

Durham’s career has been rooted in the contemporary art field, not the Native Arts field, and strategies he employs come out of that context and experience.

His suspicion of ethnic labels stems from his experiences as an artist in New York City in the 1980s, during a period of increased calls for multiculturalism. While efforts toward giving more opportunities to artists of color were well-intentioned, they also successfully maintained the essential framework of difference.

Durham emerged onto the contemporary art scene during a period in which entrenched ideas about authorship, authenticity, and the role of art were being challenged within postmodern discourse. At that time, critical strategies such as appropriation were levied to underscore how meaning is inextricably linked to context.

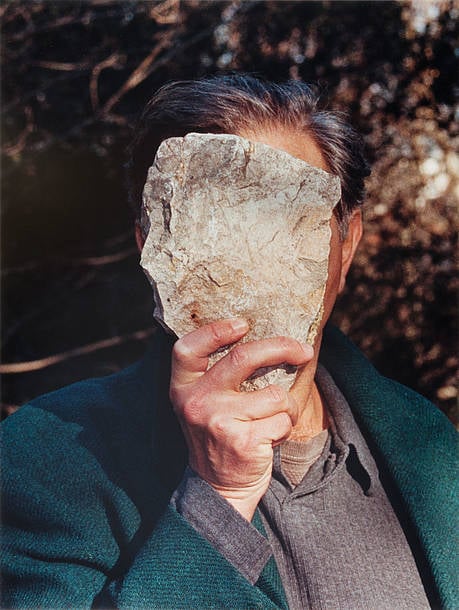

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait (1986). Courtesy of the Hammer Museum.

Thus, Durham’s contributions to institutional critique and the recontextualization of images and texts need to be understood alongside American artists ranging from Mary Kelly to Andrea Fraser to Fred Wilson, as well as other Native artists of his generation—like Edgar Heap-of-Birds, James Luna, and Kay WalkingStick—who were similarly engaged in the postmodern discourse within contemporary art at the time. Many of these artists also employed irony and satire to skewer assumptions and expectations of the type of work Native artists should be making and to reveal institutional biases.

To evaluate Durham’s work exclusively from the perspective of discourses within Native Arts field—in which, for example, the term “appropriation” provokes a different set of associations and expectations—can quickly lead to misunderstandings of the intentions and operations within the works.

The Question of Ancestry

For the past few weeks, the question that has dominated the discussion of “At the Center of the World” has been whether the artist does, in fact, have Cherokee ancestry.

In recognition of tribal sovereignty and the well-documented fact that Durham is not enrolled in any of the Cherokee tribes, “At the Center of the World” has never claimed that Durham is an enrolled member of a federally recognized Cherokee tribe (the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians of Oklahoma, or the Cherokee Nation). Indeed, Durham himself has never sought enrollment or recognition from any of the Cherokee tribes or provided information about his family history.

Jimmie Durham, Cortez (1991–1992). Courtesy of the Walker Art Center.

Moreover, the Hammer has never questioned the Cherokee Nation’s right to self-determination or to grant citizenship as they see fit. If representatives of the three Cherokee tribes choose not to recognize Durham as Cherokee, that is their right. Yet as straightforward as this principle is, it seems relevant to emphasize that historians have acknowledged the history of enrollment for the Cherokee and other tribes is in fact not uncomplicated, however well documented certain aspects of that history are.

Over the course of the past two centuries, the Cherokee diaspora separated many individuals from their communities, sometimes by choice, and sometimes by force.

As Thomas King has written:

“The Cherokee … have fifteen tribal rolls that were created between 1817 and 1914. A great many Cherokee can trace their family back to a name on one of these rolls, but unless your ancestor appears on the 1924 Baker rolls that cover the Eastern Cherokee or the 1898-1914 Dawes-Guion-Miller rolls that cover the Western Cherokee, you cannot qualify for membership in one of the three federally recognized tribes: the Eastern Cherokee, the Western Cherokee, and the United Keetowah Band. Neither the Baker nor the Dawes-Guion-Miller tools are a comprehensive or complete compilation of Cherokee families, but these rolls are the only sources that the tribe uses for determining who can be a citizen of the nation.” 3

I have been reluctant to participate in the genealogical analysis of Durham’s family tree, but a number of people have contacted me to share their responses to the evidence put forward that refute Durham’s ancestry and to question the validity of the conclusions.

The genealogical information adduced to discredit Durham (for which no sources are provided) ends abruptly on his paternal side at his great grandparents, and on the other side, is peppered with “unknowns,” all of which reflects the clear difficulties in such genealogical work.

In reviewing the family tree, it should be noted that the majority of Durham’s ancestors hail from historic Cherokee territories in the southern US states. Numerous family names on both sides of Durham’s family—Durham, Simmons, Holland, Harris, Terrell, Laney, Hill, Card, Weldon, Andrews, Garner, Reeves, and several others—appear repeatedly on both the Dawes Roll and the Guion-Miller Roll.

I am mentioning these alternate readings of Durham’s genealogy not to “prove” that he has Cherokee ancestry, but rather to point out that the information provided is incomplete and limited. Different conclusions can be drawn from it.

If Durham was raised to believe that Cherokee ancestry is part of his family history despite the lack of official registration—as he was—the question becomes whether he has any right to engage with that subject position. Durham’s detractors have made their opinion on this matter explicit: He does not.

Jimmie Durham, La Poursuite du Bonheur [The Pursuit of Happiness] (2003),

35mm film transferred to DVD, color, sound. 13:00 min. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

[W]hat seems important… is that American Indians be allowed to do their own defining, either as individuals or as tribes. This may occur on the individual level through self-identification; it may occur on the tribal level through formal membership.

One may object that self-identification allows considerable variation among individuals defined as American Indian, but American Indians have always had tremendous variation among themselves, and the variations in many ways have been increased, not reduced, by the events of history, demographic and other.”4

The Debate Over Tribal Enrollment

What is also important to add to this debate is a discussion of Durham’s longstanding political concerns about tribal enrollment.

However controversial, his criticism of enrollment is in keeping with his advocacy, since the 1960s, for internationalism in the struggles for human rights for all Indigenous peoples. His objection to the system of enrollment is rooted in a political conviction that Indigenous rights are better served by an international and pan-American approach, rather than a national one.

While studying art in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1970, Durham founded an organization called Incominidios—together with a Mapuche from Chile named Enrique Manzo and an Aymara from Bolivia named Tomas Conde—to enlist international support for Indians of the Americas and to support organizations involved in a variety of struggles.

Watching the activities of the American Indian Movement (AIM) from a distance, they actively fundraised in Europe for the organization, especially after the uprising at Wounded Knee in 1973.

Durham returned to the US in 1974 to become a full-time organizer for AIM. His distrust of national legislation and his advocacy for an international approach directly informed his role in AIM. When the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) was established at an AIM conference at Standing Rock in 1974, Durham was selected to be the director.

The purpose of IITC was to bring indigenous people from across the Americas together to argue for international recognition by the United Nations. Durham moved to New York City to take up this post in 1975 and ran the IITC office until 1979, when he resigned.5

Jimmie Durham, Head (2006). Courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

The fact that the Indigenous people of the world have the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples stems directly from Durham’s efforts during this period.

Durham was skeptical of tribal enrollment and rejected the system long before it would have affected his artistic practice personally because of the passage of the Indian Arts & Crafts Act in 1990. His opinion on the matter is quite explicit: “I am not ‘Native American,’ nor do I feel that ‘America’ has any right to either name me or un-name me.”6

Given Durham’s steadfast political position on tribal enrollment and his dedicated work as an activist for international legislation, I did not think it would be appropriate, nor my role as a curator, to strip him of his life experiences and sense of identity and present him as something he does not understand himself to be: a white man. I have known Durham for over a decade now and have spent many hours with him, speaking about his work, his life, and his strongly-held convictions. I have only ever understood him to be a person of integrity and deep commitment to act on his beliefs. He has never given me reason to question who he presents himself to be.

Were Native Opinions and Voices Enlisted?

It has been suggested that I either did not reach out to any colleagues in the Native Arts field for their input on the debate over Durham’s identity, or if I did, I ignored what they told me. America Meredith states, “Native people told Ellegood that Durham wasn’t Cherokee or Native for years, but she dismissed them and dismissed the tribes’ sovereign rights to define their own membership criteria.”

In fact, during the course of my research and preparations for the exhibition, I spoke to numerous curators, artists, and art historians in the Native Arts field. Several were later invited to participate in various facets of the exhibition and were involved in the catalogue and public programming for the show, including artist Jeffrey Gibson, art historian Jessica Horton, and curator Kathleen Ash-Milby, among several others.

Although most anticipated that the question of Durham’s ancestry would come up, without exception they expressed the opinion that the exhibition was important and should happen. None categorically declared that Durham was not Cherokee; rather, they acknowledged that it has been a point of debate in the art world since 1990, when it surfaced after passage of the Indian Arts & Crafts Act. Most shared their opinion that it had gone on for too long and that it was time to move past it.

My sense from these conversations was that there was a genuine hope that the debate over Durham’s ancestry would not dominate the reception to his work. Several noted that they believed it was a distraction from larger, more important discussions in the field of Native Arts. No one stated that I should not portray or discuss Durham as having Cherokee ancestry.

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait Pretending to Be Maria Thereza Alves (1995-2006). Courtesy of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe.

Furthermore, within the existing writing on Durham’s work dating back to the 1980s, from scholars and curators who are both Indigenous and non-Indigenous,7 the artist has been consistently understood to be of Native ancestry, and his work interpreted and written about from this perspective (along with many other facets of his life and work).

For “At the Center of the World” to disregard the previous scholarship that acknowledges his Cherokee identity or to choose not to include works that take up American Indian subject matter would itself be highly problematic.

It’s true that Durham has not been claimed by any Cherokee tribe. Yet he was claimed by a generation of American Indian activists as one of their own in the 1970s, and later, by many Native artists, curators, and scholars fighting for space in the contemporary art world.

Here is American Indian Movement leader Russell Means, speaking in 1990:

“I’ve known Jimmie Durham for more than 20 years. He’s personally never been anything but stone Indian the whole time, and I mean that in the fullest possible way. He’s never done anything but good for Indian people.”8

Curator and writer Paul Chaat Smith, who has known Durham since 1974 and worked with him in AIM, states in his essay for the exhibition’s catalogue, “…Jimmie Durham, stone-cold Cherokee Indian, even named for the famous country singer Jimmie Rodgers, like so many other Cherokee sons of the 1940s, is a lot of things, and one of them is this: Jimmie Durham is an Indian project.”9 I take Smith’s comment to mean not only has Durham been embraced by many in the Indigenous world, but that he has lived his life as an Indigenous person.

Consequences of the Controversy

Watching this controversy unfold, I have asked myself many times, “What is the goal?”

Given how little Durham’s work has been shown in the US—he has not had a significant solo show in the US since 1995—the argument that support of his work correlates in some way to lack of support for other Native artists seems dubious at best.

Jimmie Durham, Choose Any Three (1989). Courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

If the goal is to create more visibility and opportunities for Native artists, then I question how the rejection of Durham and dismissal of his contributions are in the service of that goal. As an artist, he has insisted that subjects fundamental to an understanding of American Indian history and experience be investigated within contemporary art discourse. He has also directly supported many Native artists through his writings and curatorial work.

One of the disconcerting aspects of the calls against Durham is the concern that it will harm efforts toward more support of Native artists in mainstream museums of contemporary art. Several curators and historians of Indigenous arts have expressed to me their concern that this attempt to undermine Durham’s integrity will have a negative effect, scaring non-Native curators off from wanting to work with Native artists, especially any who are not enrolled with their tribes or are somehow not officially sanctioned.

Self-determination is a political necessity, but it is no contradiction to also acknowledge that any system that legislates and authenticates identity is not without its pitfalls and imperfections.

Indeed, scholars have agreed with Durham’s fundamental premise that at times such systems can inadvertently recreate the very marginalization and oppression that they were created to resist. As Thomas King asserts:

“Among the Cherokee, you have Cherokees who are Cherokee by blood and who have an ancestor on the required rolls, and you have Cherokees who are Cherokee by blood but whose ancestors are not listed on the required rolls. The one group is ‘authentic.’ The other group is not. To my way of thinking, such a distinction is self-serving and self-defeating at the same time.”10

In 2017, is it out of the realm of our imagining to conceive that a Native person was raised not only off the reservation but apart from a tribal community and therefore did “not participate in dances and does not belong to a ceremonial ground” (as the letter in Indian Country Today states), but nonetheless was brought up with the knowledge of and respect for his/her tribal ancestry?

My concern is that positions rooted in binaries (“real” vs. “fake”) do not capture the full range of life experiences, not to mention the complexity of history, rendering a figure like Durham nearly unfathomable.

The Debate Going Forward

For those who know Durham’s work, it should come as no surprise—and certainly, it has not been for the artist himself—that this debate has erupted. After all, issues of identity and the politics of representation are fundamental to his early works. From the beginning of his career, Durham has refused to signify identity in the ways he felt were expected of him: as a victim, a “noble savage,” an angry agitator, or “a romantic Indian.”

He has tried to destabilize orthodox or officially sanctioned notions of identity and to complicate and add nuance to our understandings of a contemporary person living in a global world. His advocacy for internationalism in politics has extended into life choices and a personal philosophy rooted in cosmopolitanism. It is important to reiterate too that there are many in the field of contemporary

Jimmie Durham, Language is a tool for communication, like a city, or a brain (1992). Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

Indigenous art who believe Durham’s claims of Cherokee ancestry, celebrate the value of his contributions to the field, and have serious concerns about the divisiveness this debate is generating.

Unfortunately, in this current climate, some do not feel safe expressing their support for Durham. They fear they will be attacked for their opinion on social media or other platforms, or worse, that it will affect their careers in adverse ways. Social media can provide a false sense of consensus that does not adequately represent the many differences in opinion in the debates generated by discussions about Durham’s identity.

To me, this brings to mind something expressed by Gregg Bordowitz in a roundtable discussion on “Cultural Appropriation” in a recent issue of Artforum:

“What I’m afraid of is the politics of the litmus test, even if the objective is something I might support…. I remember in the LGBTQ movement, outing and shaming were poisonous to the atmosphere of queer activism, because they led to a litmus-test politics. And there’s an old adage on the Left: ‘When the enemy is not in the room, we practice on each other.’ That’s not a future I look forward to.”11

In some sense, the tensions between a desire and support for difference, and a political imperative for consensus are at the center of this debate. There may never be consensus about Durham’s background. I think we can all agree, however, that there are larger issues that are certainly worthy of further discussion.

The present controversy has highlighted the fact that there are differences in perspectives, practices, and discourses between the Native Arts field and the contemporary art field, differences that should be unpacked and evaluated further.

Speaking personally, my conversations with Native artists and others in the field of Indigenous arts have made me much more sensitive to the frustrations that are driving the present debate about Durham. Calls for increased knowledge of American Indian history and awareness of issues related to tribal sovereignty are very much warranted.

There is an opportunity here for all museums presenting Durham’s retrospective to create platforms for meaningful discussion rooted in respect and a desire for discourse. In fact, planning for programs to support dialogue around these issues are already being planned. I believe there are shared goals here: to support deserving artists and to fight for social justice for all people, no matter their background.

I remain hopeful that Durham’s work will continue to push the discourse forward, as it always has, so that we can discuss difference in ways that are not antagonistic, however difficult that may be at certain moments.

Endnotes

- “Before the Law: Jimmie Durham in conversation with Kasper König,” Wiels, Brussels, September 16, 2011.

- Robin Cembalest, “What’s in a Name?” ARTnews (September 1991).

- Thomas King, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2012).

- Gail K. Sheffield, The Arbitrary Indian: The Indian Arts and Craft Act of 1990. (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), 87.

- Durham outlines in detail his reasons for resigning in his 1980 essay “An Open Letter on Recent Developments in the American Indian Movement/International Indian Treaty Council,” published in his book A Certain Lack of Coherence (Berkeley: Kala Press, 1993).

- Durham made this statement at the time of the passage of Indian Arts & Crafts Law and it is included in Nikos Papastergiadis & Laura Turney, “On Becoming Authentic: Interview with Jimmie Durham,” Prickly Pear Pamphlet no. 10 (Cambridge, UK), 1996. This interview is a good source for a discussion by Durham about his opinion on tribal enrollment and related matters.

- Respected scholars and curators of contemporary art who have presented and written on Durham’s work include Iwona Blazwick, Guy Brett, Dam Cameron, Luis Camnitzer, Bart de Baer, Isabel Carlos, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Jean Fisher, Anselm Franke and Hila Peleg, Greg Hill, Richard Hill, Hou Hanru, Jan Hoet, Candice Hopkins, Jessica Horton, Jeanette Ingberman, Miwon Kwon, Lucy Lippard, Rosa Martinez, Declan McGonagle, Gerald McMaster, Laura Mulvey, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Jack Rushing, Allen J. Ryan, W. Jackson Rushing, Juan Sánchez, Richard Schiff, Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Dirk Snauwaert, Elisabeth Sussman, Harald Szeemann, Michael Taussig, Laura Turney, and Mark Watson, among many others.

- This quote appears in Ward Churchill’s book From a Native Son: Selected Essays in Indigenism, 1985-1995, (New York: Southend Press, 1999), 483.

- Paul Chaat Smith, “Radio Free Europe,” in Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and DelMonico Books, Prestel, Munich, London, New York, 2017).

- King, ibid.

- Cultural Appropriation: A Roundtable,” Artforum (Summer 2017).