“When I first showed the city footage in Poughkeepsie, [artist] Liam Gillick said to me, ‘Anri, tell me the truth. Tell me that this city does not exist. Please tell me that you do not have an artist-Mayor friend?”

So runs a title card appended to Dammi I Colori (2003), one of the works on view in Albanian-born artist Anri Sala‘s lovely, freshly opened three-floor retrospective at the New Museum. The 15-minute film meditates on the urban beautification program of Tirana mayor Edi Rama, the “artist-Mayor friend” to whom Gillick referred.

Rama attempted to rally citizens of the impoverished post-Communist capital by decorating its decaying housing with cheerful blocks of color, a touching expression of faith in the redemptive power of aesthetics.

The tale is no artistic concoction of Sala’s, however; in fact, Rama would go on to become Prime Minister of Albania, a post he has held since 2013. The New Museum show even contains a display of drawings co-authored by the two men, who were longtime friends, with doodles inked on official government emails.

Anri Sala, Intervista (Finding the Words), 1998 (still).

Image: © Anri Sala. Courtesy Idéale Audience International, Paris; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Johnen Galerie, Berlin; and Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich.

Sala came to Paris to study in 1996. By 1998, as an art student, he had created the film Intervista (Finding the Words) (1998), which will be screened on Wednesdays in the New Museum’s basement theater. That work involves Sala confronting his own mother with footage of her days as a virulent supporter of former Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha.

The work was almost immediately celebrated as introducing something important to art via its sophisticated reckoning with history—yet it was exactly that history that Sala was itching to escape. “I did not want to fall back into a type of work focused only on my identity and biography: I was afraid that it could become a prison,” Sala states in the catalogue for the exhibition. “So I made a conscious choice not to work in that direction.”

If you stitch the various videos in this show into one decade-and-a-half long narrative, it is the tale of this escape. Time and again, his art allegorizes the idea of art itself as a vehicle of transcendence, and of the failure to attain such a state of being.

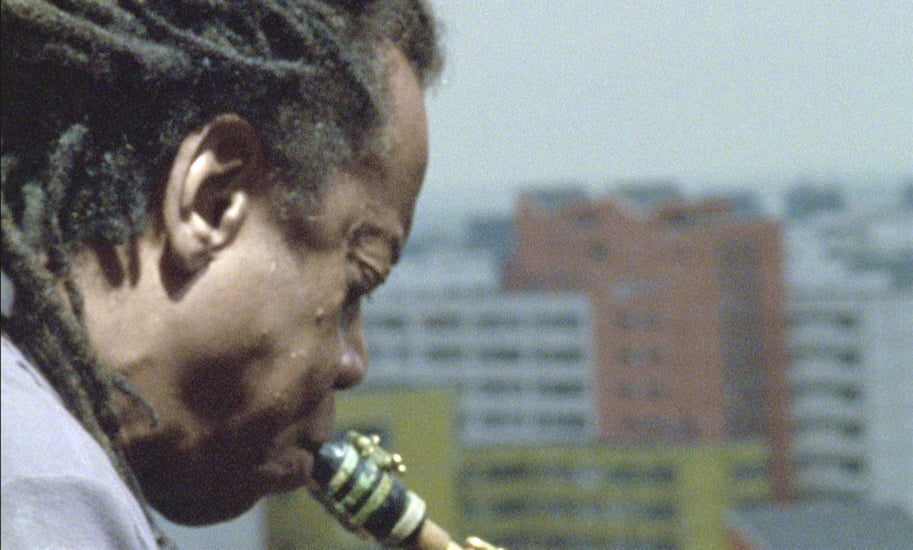

In Dammi I Colori, the pathos is generated by the contrast of post-Communist squalor against those quixotic colors. Two years later, in Long Sorrow (2005), there is a similar contrast, this time between the images of the stolid mass of a bleak Berlin apartment block (“Long Sorrow” is its nickname), and a lone saxophonist that the camera unveils perched on its balcony, engaged in a tortured improvised solo.

Berlin is where Sala came to take up residence as an artist, so the trajectory traced by the subject matter of these two videos is literally the trajectory away from Tirana, as his themes become more purified, more refined, and more global.

The charming Tlatelolco Clash (2011) is set in Mexico City’s Plaza of the Three Cultures, the site of, among other things, an infamous 1968 massacre of student protesters by government forces. In the video, we see, one after another, locals stand in front of an old-fashioned hand-cranked music box, and feed in punch cards. What emerges is a rickety instrumental version of the classic Clash punk-rock anthem “Should I Stay or Should I Go?,” their seemingly isolated acts edited together to form a whole.

Installation view of Anri Sala, Revel, Revel (2013)

Image: Ben Davis

Mexico City is the site of Sala’s blue-chip art gallery kurimanzutto, so the setting here again marks the widening radius of his movement into the international art scene, away from the “prison” of biographical themes.

Sala’s most recent works, of which there are several examples here, tend towards theatrical installation, and have often focused on the theme of classical music. Among these is the 22-minute Ravel Ravel (2013), originally commissioned as a German/French collaboration at the Venice Biennale, and a showstopper.

It features two screens, each with a close up of a hand playing Maurice Ravel’s shimmering masterpiece Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D-major. It is staged deliberately so that the two pianists’ performances of the same piece move into and out of phase with each other, at times lining up, at times uncoupling to create contrapuntal chaos.

Anri Sala, Ravel Ravel, 2013 (detail).

Image: © Anri Sala. Courtesy Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Marian Goodman Gallery; and Hauser & Wirth.

It is an utterly mesmerizing sonic experience. Here, the vivid images of the streets of Tirana, Berlin, or Mexico City from the earlier works have been replaced with the sterile anechoic chamber as a background. The animating dance between cultural glory and worldly grit has been channeled into the tension between a piece of great music and its dissonant interpretation.

In the show catalogue, Boris Groys argues that the ultimate underlying message threaded through Sala’s work is that “behind the illusion of the same he discovers a plurality of unpredictable and uncontrollable individual variations.” Were this indeed the ultimate horizon of the work, that would do little to explain what makes it stand out; this is almost a stock theme within contemporary video art.

Curator Massimiliano Gioni gets closer to the heart of the matter in his interview in the same catalogue, when he notes what made Sala seem so unique in the mid-90s: “There is not only a preoccupation with truth, but also a devotion to sincerity which runs through many of your early works and which represented a dramatic contrast to the more medium-specific, decontructivist work of other artists at the time.”

Western European video art, coming from developed “societies of the spectacle,” tends to obsess with a fully dominant mass media as the tortured condition that both self and the art object define themselves against. If Sala were, as Groys suggests, ultimately interested in unmasking the “illusion of the same,” his endeavors would be little different than, for instance, the French artists Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe’s “No Ghost Just a Shell” project, which drafted a raft of fellow artists into making their personal films using a stock anime character, or the British artist Phil Collins, who has created videos of people from around the world doing heartfelt karaoke versions of The Smiths song “The World Won’t Listen,” as a way to explore how people find political meaning.

In temperament, Sala is closer to the “neo-Romanticism” of an artist like Ragnar Kjartansson—from Iceland, a country that was also relatively poor and definitely on the periphery of Europe until recent decades—who also has made art of filmed musical performances, and claims the practice as a thoroughly sincere vehicle for emotional expression. Sala, however, lacks Kjartasson’s wackiness, and has a less pop, more classical gravitas.

Groys hypothesizes that the Albanian artist’s style reflects the “aftereffect of Sala’s experience of a ‘totalitarian’ past, which produced in him the desire to defend the individual and vital against the bureaucratic and mechanic.”

These days, Prime Minister Rama is trying to enter the European Union, declaring that the region may relapse into ethnic conflict if it does not receive the stabilizing imprimatur of Europe’s embrace. To outsiders, this may very well seem odd. It comes at a time when broad swaths of EU population have turned against the the whole project as a destabilizing force.

Even today, it seems, European cosmopolitanism has a different connotation in post-Communist Albania than elsewhere. Fortunately, the cultural stakes are very different than economic and political ones.

But I think that this shows a thread that accounts for the difficult grandeur in Anri Sala’s work. There’s a complexity and cerebral quality to his art, certainly. In the more recent work, he has become more hermetic and purely lyrical in his concerns. But beneath it all, too, he still insinuates a belief in art’s power that a cynical, media-savvy audience might have difficulty believing in, but can share through his reflected light.

“Anri Sala: Answer Me” is on view at the New Museum, through April 10, 2016.