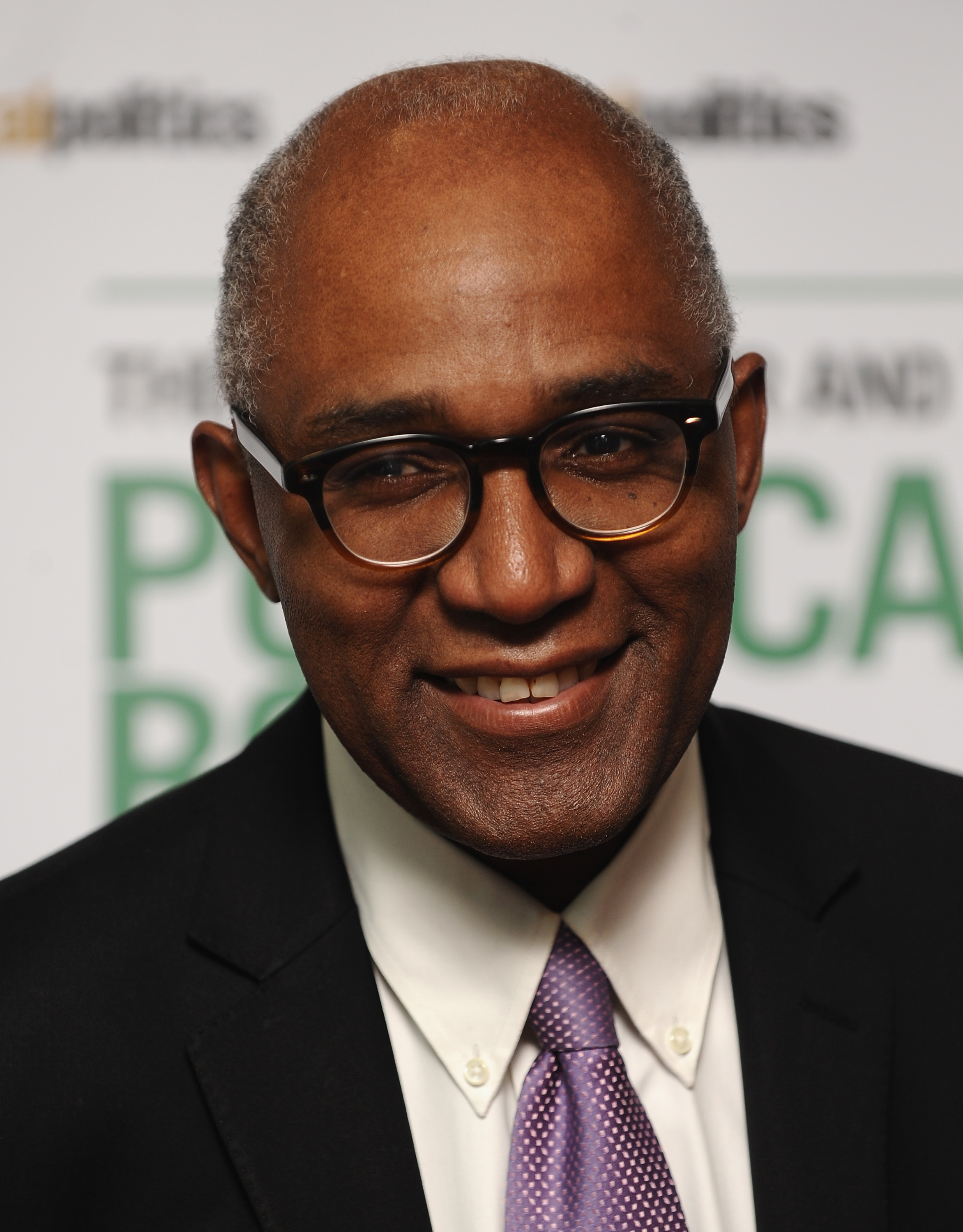

The debate over how history is presented got more complicated in the U.K. last week, when Trevor Phillips, the British writer, journalist and Policy Exchange think tank member, published a set of guidelines for the “reinterpretation of history” in any form, whether it be tearing down statues or renaming streets. The paper, which calls for institutions to create clearly defined committees to oversee any changes, and for those members to be held accountable to any supporters, “including the taxpayer”, has met with approval from some museum leaders. But many others in the cultural field have so far remained silent, while more vocal critics in the media view the report as “anti-woke” backlash to progressive change.

Tensions over problematic historical monuments in the U.K. came to a head last year when a crowd of Black Lives Matter protesters in Bristol threw a long-contested statue of Edward Colston, a local businessman and philanthropist with connections to the Atlantic slave trade, into the river Avon—altering history in a decisive moment.

The statue of Colston being pushed into the river Avon. Photo by Giulia Spadafora/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

Since then, a debate has raged on over what happens to historic tributes when their present-day context has drastically changed. In a few years, streets have been renamed, dozens of statues have come down and new ones have been erected in their place. For example, in Hackney, northeast London, an initiative to commission permanent works of public art by artists connected to the Windrush Generation—Caribbean-born citizens of the former British empire who came to live in the U.K.—including Thomas J. Price and Veronica Ryan, has been well received by community members and the press.

Some controversial monuments remain, however, including one dedicated to Cecil Rhodes, a former Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in southern Africa and staunch imperialist, at Oriel College, University of Oxford.

These changes have come into play due to local pressure, arguments made on and offline, and campaigns from all sides of the political spectrum. Phillips’s paper calls for more official bodies to be formed that would decide on any changes, taking power away from protest groups and public opinion.

Veronica Ryan OBE, Custard Apple (Annonaceae), Breadfruit (Moraceae), and

Soursop (Annonaceae) (2021). Courtesy the artist, Paula Cooper Gallery and Alison Jacques. Photo: Andy Keate, 2021.

The paper, titled History Matters, has been published by the center-right think tank Policy Exchange. The organization regularly puts out a “rolling compendium” of information on this topic and staged a conference under the same name earlier this year.

Labelled as an “anti-woke charter” in much of the press, the paper was backed by three museum leaders whose support is published in its opening pages.

“These guidelines make a very useful contribution to the debate,” said Nicholas Coleridge, the chair of the Victoria and Albert Museum. “Practical, rigorous and above all sensible, I am certain any board or institution would do well to study them carefully instead of arriving at some drastically hasty, prejudiced and wrongheaded decision.”

Sir Ian Blatchford, director of the Science Museum, echoed this sentiment, calling the report: “a resoundingly reasonable guide to achieving change that it thoughtful and sustainable, rather than anxious and panicked.”

Dr Samir Shah, chair of the recently renamed Museum of the Home—formerly the Geffrye Museum, named after the London merchant and slave trader Robert Geffrye—also gave his endorsement. The report’s “principles will be of inestimable help to our institutions, and those charged with guarding and guiding them, as they deal with the issues surrounding their heritage assets,” he said.

With such support, Phillips’s recommendations could have an impact not only on historic monuments, but future commissions, institutional naming rights and beyond.

The paper’s release also came two days before the U.K. government budget was announced on October 27, during which chancellor Rishi Sunak raised the review of the “Museums Freedoms” programme, which gives national museums broad authority to use their government funding as they see fit. Could this point to fundamental changes in how much influence the government has on national museums and public art in the U.K.? The sector will soon need to find some clarity.