As rare as it is for the debut of any artwork to be a political event, it might be rarer still for the completion of a presidential portrait to be an artistic event.

But there we were on Monday morning at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, to witness the unveiling of the official portraits of the former President and First Lady. The museum’s courtyard was packed with a cavalcade of liberal big wigs, various art-world power players, the vulpine swarms of the press corps, and, conspicuously better dressed, the donors looking to see what their money had conjured up. It was a scene.

What accounts for the staggering buzz around these presidential portraits, usually a fairly routine affair?

Compared to the current White House occupant, almost anyone would look like a paragon of taste and cultivation. But Barack and Michelle Obama really had art cred. From the moment they entered the White House, they proved to be uncharacteristically open to contemporary art. As they took up their new residence in 2009, they caused an admiring stir among the smart set by requesting works including an Ed Ruscha and a Glenn Ligon as décor.

An openness to conceptual art may be a relatively minor breakthrough within the overall record of Obama’s legacy—but it is part of that legacy, and it is reflected in the artists commissioned to paint them.

The choice for Obama’s portrait, Kehinde Wiley, is one of the most pop-culture-friendly of art-market stars, known for combining bombastic scale, art-historical reference, and social relevance, originally by casting young men off the streets of Harlem and styling them as European royalty. His instantly recognizeable portraits have given him rare reach, enabling him to collaborate with FIFA and see his paintings on the hit TV show “Empire” while, at the same time, scoring a career retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum.

The furor over his Obama portrait’s debut at the NPG is, in part, a testament to the fact that the gamble of picking such a strong voice paid off—though in a curious way.

(I’m going to focus on Kehinde Wiley’s fantastical rendering of Barack Obama, rather than Amy Sherald’s stylish image of Michelle Obama, even though I like Sherald somewhat more as an artist. Her painting of the First Lady in muted tones in a geometric-pattern dress deserves its own essay. I just think that Barack, having the complex record of two fraught terms as the most powerful person in the world, presents the more fearsome symbolic challenge.)

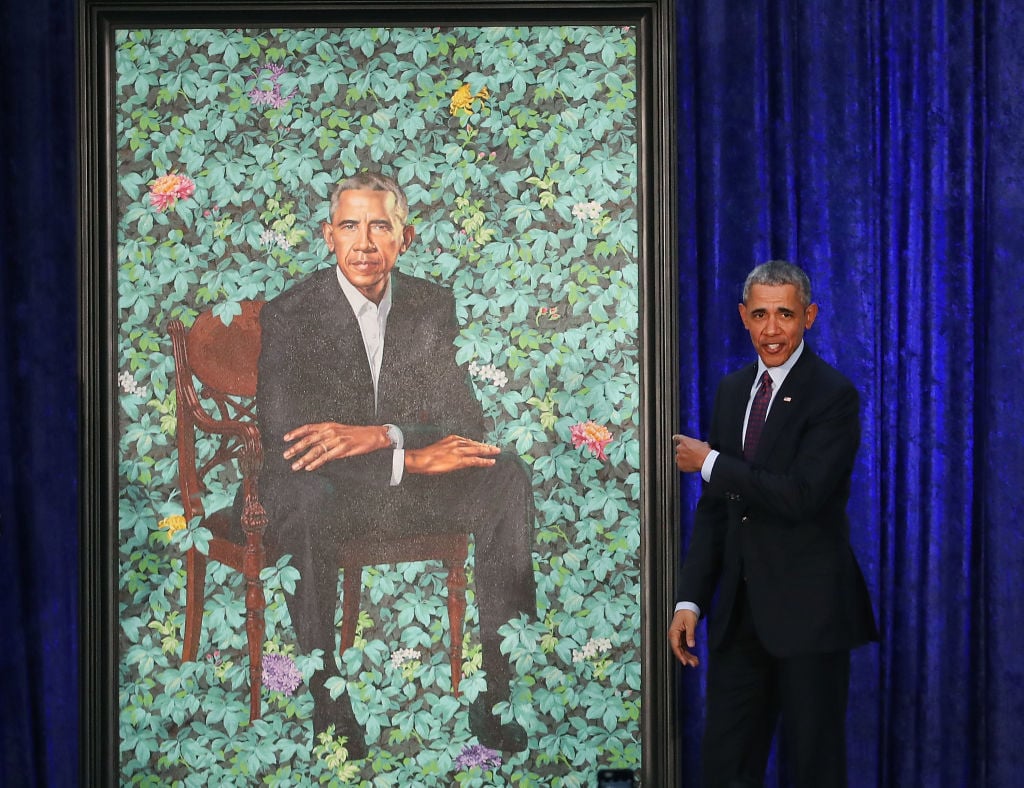

Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley, oil on canvas, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © 2018 Kehinde Wiley.

What I like the most about Wiley’s presidential painting is exactly what might, on first contact, confuse a casual observer. Featuring the seated president posed against—almost floating on top of—a seemingly living backdrop of foliage and flowers, it is weird, and that makes it memorable.

It is these unconventional details that have won the picture instant meme status. The only precedent that came close to generating that kind of excitement over a presidential portrait was the tingle of scandal when painter Nelson Shanks revealed, back in 2015, that he had secretly hidden a reference to Monica Lewinski’s dress in his official portrait of Bill Clinton—and that’s obviously not the kind of viral attention any public figure wants.

As for the more conventional task of giving a sense of the man’s character, to my eye Wiley has never been particularly effective at capturing the inner life of his sitters. Characteristically, his subjects have the indistinctly smoldering gaze familiar from fashion ads. (He actually worked with the designer Riccardo Tisci on his “Economy of Grace” series.) Though some may disagree, I think the same holds true of this portrait of Barack Obama.

The 44th president looks elegant and confident in his official portrait—but nothing about his expression or appearance would make it, on its own, a particularly signature or memorable image. (Obama’s official photographer, Pete Souza, leaves behind a mammoth record of just how uniquely and charismatically expressive Obama could be.)

The pose Obama is pictured in is conventional. Ever since Gilbert Stuart’s 1805 portrait of Thomas Jefferson, the seated presidential portrait has been a way to deliberately cultivate an air of “chaste republican character.” The seated president is intended to project the Commander-in-Chief as Man-of-the-People, as opposed to the more regal style of standing portrait that immortalized George Washington.

In its particular emphasis on informality—Obama is not at a desk with his papers, like Jefferson—Wiley’s painting reflects the changing conventions in our age of relatability politics, when “which candidate you would rather have a beer with?” is something pundits muse about. Indeed, in his casualness (though not in his serious expression), Wiley’s Obama echoes Robert Anderson’s 2008 portrait of George W. Bush, which showed its subject seated on a couch, hands on his knees, a vase of flowers behind him to suggest domestic intimacy.

Robert Anderson, George W. Bush (2008). Image courtesy National Portrait Gallery.

Within art history in general, it’s no accident that the great portraits tend to be self-portraits. With only themselves to answer to, artists can expose the kind of vulnerability or candor that yields the memorably human.

Portraits of the powerful tend towards the inert by the nature of the relation implied in their commission: power demands worship; worship demands myth; and myth tends towards formulae.

Faced with this obstacle, the clever portraitists often resort to the indirect means of style and staging to convey a singular identity or story. John Singer Sargent’s 1903 depiction of Teddy Roosevelt, for instance, conveys an air of casual and natural authority. A man-of-action vibe is suggested by the setting—a stairwell, with Roosevelt’s hand perched confidently on a newel, placing him somewhere between the entry hall and the drawing room, between woodsman and statesman—a neat way to mythologize the Rough Rider image.

In my opinion, this is the most stylish of all presidential portraits. Its savvy artistic myth-making, however, only half distracts me from the small historical fact that Teddy Roosevelt was a ruthless imperialist.

The mercenary glamour of Sargent’s portrait was part of the attempt to shape the historical record to Roosevelt’s favor. And that, still, is the vocation of this arcane tradition—even in its cool, contemporary, rebooted version under Obama.

Because of course, the public clamor around the NPG unveiling is not mainly about interest in the art of Kehinde Wiley or Amy Sherald. It is an opportunity for a bruised-and-battered liberal audience to comfort itself with the ennobled imagery of its own heroes.

Just now, Obama’s image doesn’t really need that much massaging. The rise of Trump spiked Obama’s approval ratings. Sometimes a healthy dose of contrast is the best PR.

But let’s be honest: Comparison to Trump is a low bar to clear. Even George W. Bush, now rebranded as a painter and seeming positively affable next to Trump, has seen his approval ratings soar—and that guy started two calamitous wars and presided over the most catastrophic economic crisis since the Great Depression.

The NPG’s wall text for Wiley’s Obama portrait is worth quoting. It is written in the institution’s characteristic mode, which you can describe as “light contextualization”:

Barack Obama born 1961

Forty-fourth president, 2009-2017Barack Obama made history in 2009 by becoming the first African American president. The former Illinois state senator’s election signaled a feeling of hope for the future as the U.S. was undergoing its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. While working to improve the economy, Obama enacted the Affordable Care Act, extending health benefits to millions of previously uninsured Americans. Overseas, he oversaw the drawdown of American troops in the Middle East—a force reduction that was controversially replaced with an expansion of drone and aviation strikes. Though his mission to kill al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden was successful, his pledge to close the Guantanamo prison went unrealized.

This is a rather strained bit of text. On the one hand, it makes plain the obvious fact that, if this painting’s unveiling is being treated as a special event, it is because, as the first African American president, Barack Obama bore a special kind of symbolic burden.

Throughout his career, he was attacked and demonized as an alien presence—including by the man currently at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, who built his career on “birtherism.” And just as there was a deep significance to an African American family taking up residence in a house built by slaves, there is a particular weight to Obama claiming the genre of presidential portrait, originally a tool to project the benevolence of slaveholding Founding Fathers.

You can write this off as merely symbolic—but then, the trolls are already trying to stir up animus about Wiley’s previous work depicting black female figures decapitating white men. So you can’t really take the importance of symbolism for granted.

At the same time, the very ginger treatment of Obama’s larger political legacy in this wall text shows how complicated his legacy is, and just how much is at risk of being flushed down the memory hole as we look at him through a rose-colored cloud of Trump exhaust.

Even just confining ourselves to the public policy matters at immediate issue in the age of Trump, those concerned about executive overreach might remember that Obama not only presided over the rise of drone warfare, but the extrajudicial killing of US citizens and the limitless extension of the NSA’s digital surveillance program—all precedents he passed on to his maniacal successor. When that became a crisis after the Snowden leaks, Obama enacted a shock-and-awe crackdown on whistleblowers, invoking the Espionage Act more than all previous administrations combined.

And as for the decisive Trump-era wedge issue, immigration, admiration for Obama’s famous executive order defending the Dreamers has to be tempered by the fact that Obama himself oversaw wrenching levels of deportations. This bit of his legacy led the head of the National Council of La Raza to brand him, scathingly, the “Deporter in Chief.”

Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama at its unveiling at the National Portrait Gallery. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

And so, returning to Wiley’s portrait, I’d say what’s interesting about it is how the image encodes this double symbolic legacy.

Obama appears to me to be awkwardly perched on the edge of his chair. His image seems to be both detached from the background, floating strangely atop it, and at danger of being sucked back and consumed by it. In this, Wiley’s atmosphere calls to mind the image of the President who, as Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote, “for eight years walked on ice and never fell,” navigating America’s brutalizing racial hangups.

At the same time—and I know now that I am reading against the grain of the painting—I think Wiley’s fanciful style ends up leaving the aftertaste of self-awareness about its own myth-making. He has rendered Obama’s image as otherworldly. Somewhere, deep down, on the level of subtext and unintended meanings, this strange, strange political portrait ends up being about how the man must be abstracted from the nitty-gritty of his legacy to become the symbol that his followers desire him to be.