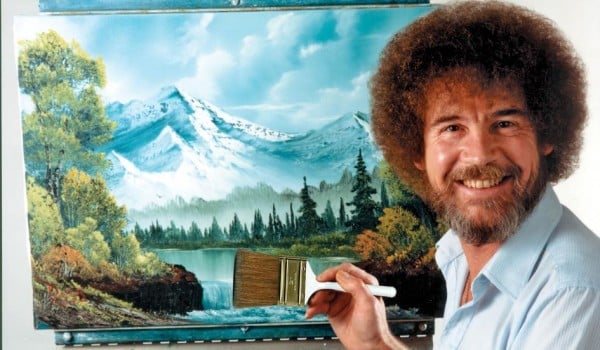

It’s way too early in the morning as I write this, and yet currently about 40,000 people are gathered together on the Internet, to watch and chat in one big hive mind as the late Bob Ross paints his “happy little trees” onscreen.

When I checked out at around 12:30 a.m., there were roughly 60,000 people watching, as the live broadcasting site Twitch commenced what will be a nine-day streaming marathon of the Joy of Painting, Ross’s immortal Muncie, Indiana-based instructional painting show.

Apparently, it’s a lot more immortal than we thought—close to undead. And with an army of followers.

Screen capture of “The Joy of Painting Marathon” on Twitch

Viewership numbers can seem totally meaningless on the Internet. It’s even possible that in Internet terms, 40,000 and 60,000 don’t seem like a big numbers. But the key point is that the people watching Bob Ross are watching it live, together. In this age of binge-watching Netflix shows, and our increasingly fragmented viewing habits, the idea of so many people collectively watching Ross work his mild magic on canvas is somewhat amazing.

Yesterday, Twitch sent me the press release about the Bob Ross Livestream Marathon. I looked it over, thought about it briefly, and decided it wasn’t a story. Just last week, the Joy of Painting had been unleashed upon YouTube for the public’s delectation, and streaming it seemed a bit redundant.

Silly, silly me! Last year, I actually wrote a story for New York about Twitch, published just before Amazon paid close to $1 billion to buy the site, which specializes in letting people watch their friends play videogames live. I talked to about 20 gamers, journalists, and fans for that story. And the key conclusion was that the narcotic allure of “liveness” changes everything.

In this case, it has changed a PBS show that has been off the air for two decades, and that consists of a lone man cooing softly about “Van Dyke Brown” and “Prussian Blue,” into a kind of telepresent Woodstock for nerds. “Bob Ross on Twitch” is a collective experience—or at least the semblance of a collective experience—likely more magnetically so in this format than the original Joy of Painting ever was.

Screen capture of chat bar during “The Art of Painting Marathon” on Twitch

Twitch’s secret—the secret that makes it valuable enough to have sparked a bidding war between Google and Amazon—is not just liveness, but liveness-plus-community, what is happening on the main screen plus the chat bar where viewers weigh in and joke with each other, at the right, which gives you the sense that you are experiencing something together.

In effect, Twitch very effectively incorporates the so-called “second screen” into the main event, the space of Twitter color commentary and text-message badinage that advertisers fear is stealing attention from their mind-control efforts. The responsive layer of the experience sutures the viewership in like a fine coat of finish.

As for the chat around Bob Ross, I warn you, it does not exactly scale the heights of aesthetic discussion. The effect is mainly something like walking through a crowd in a stadium as people yell past each other excitedly about the game.

There is a lot of chatter like, “those trees look happy” or “Bob Ross is the man.” There’s a lot of teenage boy banter (see above). There’s a lot of joking pretending that Bob Ross is actually broadcasting live, trying to get his attention or jokingly telling him to pay more attention to the chat.

There’s some talk about ASMR—the tingly brain phenomenon that some people get watching whispery Internet videos, and that some credit for the Joy of Painting’s odd appeal—riffing on Ross as an “ASMRtist.” You will also see a tidal wave of the “KappaBob” emote, a hieroglyphic of a man’s head “afroed” in Bob Ross style (an inside-joke too complex too explain here), showing that the viewership here is mainly core Twitchers.

Twitch cartoon of “KappaBob” for the launch of Twitch Creative

Is there anything that makes this most rear-guard of artists particularly amenable to vaulting ahead, and becoming fodder for what is in effect a teeming work of unintentional post-Internet art? Well, Bob Ross is very famous, there’s that, and he’s an object of kitsch affection. His paintings themselves are comfort food, reminding you of something you’d find on the wall at a three-star bed and breakfast.

But watching Bob Ross “live,” maintaining his steady patter and conjuring up his landscapes with a few swipes of grease, what strikes me is what a great performance artist he is. Everything about the setting—the black background, the guileless editing, the steady patter—reminds you of a magic show. That’s what it really is, since the “joy” here is obviously of painting as a verb and not a noun, of watching Ross deftly conjure something out of nothing rather than the final something he conjures.

That’s what makes the Joy of Painting a perfect vehicle for Twitch, where this marathon is part of the launch of its new Creative vertical. Artists of various kinds have long used the platform to broadcast themselves at work—mainly DeviantArt fare: a lot of dragons, robots, and anime maidens—and now they will have their own space where they don’t have to compete head-to-head with videogame streams. “[U]nleash your inner Bob Ross,” the press release says, “and get creative.”

Twitch is ecumenical about what counts as “creative,” but it is specifically asking that it be a space for showcasing the “creative process,” not, say, streaming finished works of animation. “People on Creative love watching each other make tangible creations, and that is what we would like to encourage,” the FAQ explains, adding sternly, “There are no current plans to lift this restriction.”

Reading Twitch’s guidelines, I would say they have difficulty defining what this prohibition really means, describing it as the difference between broadcasting yourself doing stand-up comedy (forbidden) and broadcasting yourself brainstorming jokes (encouraged). The Joy of Painting itself is an example of a program where the broadcast blurs process and product.

Screencapture of archived broadcast from Geers_Art

For that New York story I talked to Darren Geers, who streams as Geers_Art and is one of the artists Twitch Creative is touting in its take off. Here is what he told me about how he views the contemporary media landscape, and what draws him to Twitch as an artist:

Steaming and YouTube are my two primary sources of entertainment media outside of videogames. I don’t watch any TV. The level of content seems so dumbed down. I watch it and I have to roll my eyes because it is the most ridiculous type of editing. There’s no realness at all. When you are interacting with someone on Twitch or you are watching a Twitch channel, you are watching someone live. They can’t be fake to the extent that a TV program can be. If you try to be fake or pull something over, you still have to maintain a level of realness. That’s probably the main thing that attracts me to that form of entertainment.

That, it seems to me, is a very good account of the pressures on the way we think about media and art in the present.

The more filtered your world is by screens and media, the more hungry you are for directness, realness, rawness. The more virtualized entertainment gets, the more it circles back on itself to provide mediated versions of realness. The more images you consume, the more hungry you are to see the process behind them, to the point that the process itself becomes a kind of product to be consumed. It is probably some kind of artistic bellwether that this is what Twitch is building its billion-dollar media empire on.

Click on over to watch people watching Bob Ross. It’s a happy little glimpse into the future.