Starting with Barack Obama’s announcement last December that relations between the US and Cuba would be normalized, more Americans traveled to Cuba than at any time since the revolution took place in 1959. Since then, there has been a flood of announcements stateside for upcoming Cuba-related events, panels and exhibitions. The fact is that 2016 is shaping up to be the year more Cuban art travels to US shores since Fidel Castro donned green fatigues and grew out his hipster artist beard.

It’s only January, and already in New York this new art-forward bilateralism can be seen in a pair of excellent shows at blue-chip galleries: David Zwirner and Sean Kelly. Though the exhibitions are of entirely different vintages—one gathers works by a little known group of 1950s abstract painters, the other features the New York debut of a sparky conceptualist—both provide glimpses of a parallel art world.

At times, this alternate universe runs on a similar track to US developments; at others, it peels off into retrofuturist fireworks. Jointly, these exhibitions suggest the existence of what quantum physicists call a “multiverse”—a region, located possibly in the Caribbean, where familiar problems beget other conceivable outcomes, be these cosmological or artistic.

Installation view, Concrete Cuba, David Zwirner, New York (2016)

Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

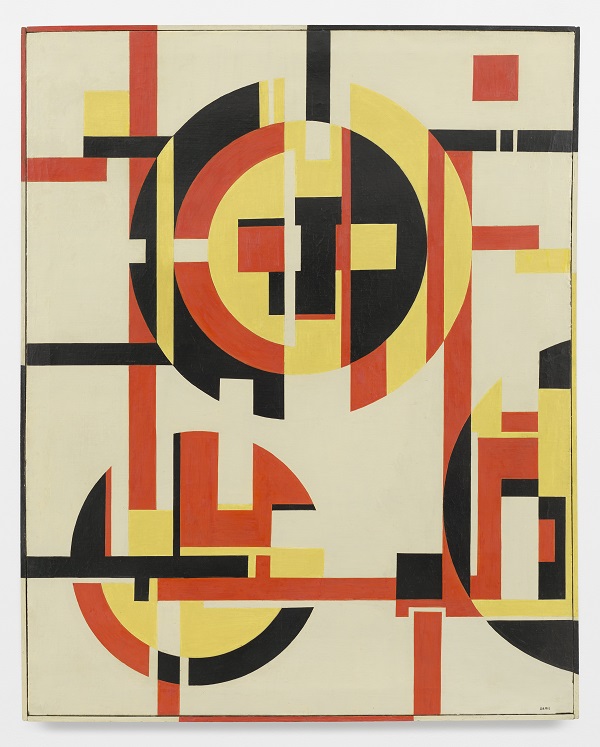

One place in Manhattan to get that twitchy Twilight Zone feeling is at David Zwirner’s 20th Street gallery, home presently to the exhibition “Concrete Cuba.” The show features more than three-dozen paintings, drawings, and sculptures by a group of postwar Cubans who, between 1959 and 1961, styled themselves Los Diez Pintores Concretos (Ten Concrete Painters)—in English, the Latin counterparts of Piet Mondrian and Josef Albers. Mostly, the display fleshes out a largely forgotten chapter in the history of the global avant-garde, while providing a peep at a radically different modernity (in Cuba concretism coincided with political tumult and rapid urbanization). Fittingly the show also channels vintage Rod Serling: an exhibition by the same name was staged at Zwirner’s London digs last September, so this do-over features different artworks by the very same artists.

A museum-quality show, “Concrete Cuba” celebrates the movement’s connections to better-known figures, like the Dutchman Theo van Doesburg and the Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-García, while promoting the modest advances made by Los Diez (the group managed to exhibit together only three times). Where European, and later American, hard-edged abstraction was pared down and stripped of symbolic content, these Cuban artists adapted non-objectivism—often despite their own theoretical premises—to their particular circumstances. On the evidence, Los Diez snuck some son into Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie—especially as seen in their use of curved lines, circular shapes and pastel colors.

Diana Fonseca Quiñones

El Capital (2015) (detail)

intervention in three volumes of Das Capital by Karl Marx

Photo: © Diana Fonseca Quiñones

Photography: Jason Wyche, New York

Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

At Zwirner, the island’s different swing makes key appearances in several of the exhibition’s best works. Note, for example, the untitled bronze and metal stabiles by the group’s lone female artist, Loló Soldevilla, which approximate pregnant forms. Then there are the circular and semicircular lines employed by Luís Martinez Pedro in a pair of paintings that share the title Aguas Territoriales (Territorial Waters)—they resemble oceanic ripple motifs. And then there is Mario Carreño’s Sin título, composición (Untitled, Composition), a brightly hued arrangement of geometric forms that, on the one hand, presents a composition of harmonious planes and colors, but also suggests palm trees and hourglass figures.

Though separated by half-century of volatile history, Diana Fonseca Quiñones’s show of paintings, sculptures, and videos at Sean Kelly espouses a similar if less buttoned-up self-reliance.

Diana Fonseca Quiñones

Untitled, from the Degradaciones series (2015)

Photo: © Diana Fonseca Quiñones

Photography: Jason Wyche, New York

Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

The recent winner of the 2015 Artnexus Latin American Art Award, Fonseca Quiñones’s work is a rare combination of DIY economy—of the sort made ubiquitous by LES galleries—and profound metaphor making. Among her videos is the highly economical Pasa Tiempo (Pastime), which shows the artist stitching an airplane on her hand. Elsewhere, a series of three paintings titled Degradación (Degradation) mobilize chunks of paint recovered from Old Havana’s rundown buildings into hand-piled palimpsests. Staring at them evokes Havana as Pompeii—the mother of all archeological digs.

Despite the similarities of Fonseca Quiñones’s pieces to that of other contemporary artists, her art comes off as virtuosically original. Her usual medium is everyday objects, which she marshals into unexpected combinations that cover themes from romantic love to social protest.

Consider, for instance, the pair of matches she videotapes being fired together to enact a wavering death dance. In another multimedia piece, titled Simulación y simulacro (Simulacra and Simulation), a real-life rotating fan appears to turn the videotaped pages of Jean Baudrillard’s book by the same name. The effect of these spare works is stunning. The idea that such familiar stuff can contain fulsome poetry blows the mind.

Luis Martínez Pedro,

Aguas territoriales (Territorial Waters) (1963)

Photo: © 2016 Luis Martínez Pedro; courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Which brings me back to why the coming avalanche of Cuban art is good news for the art world in New York and elsewhere. Among the scheduled shows of Cuban art in the next few months are painter Alejandro Campins at Sean Kelly in February, Carmen Herrera’s fall retrospective at the Whitney, and the Bronx Museum’s upcoming survey of work from Havana’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes—but more are sure to come. Whether these and other offerings arrive in the form of historical exhibitions or as shows by unknown artists, they’re bound to make the familiar look new and weird again.