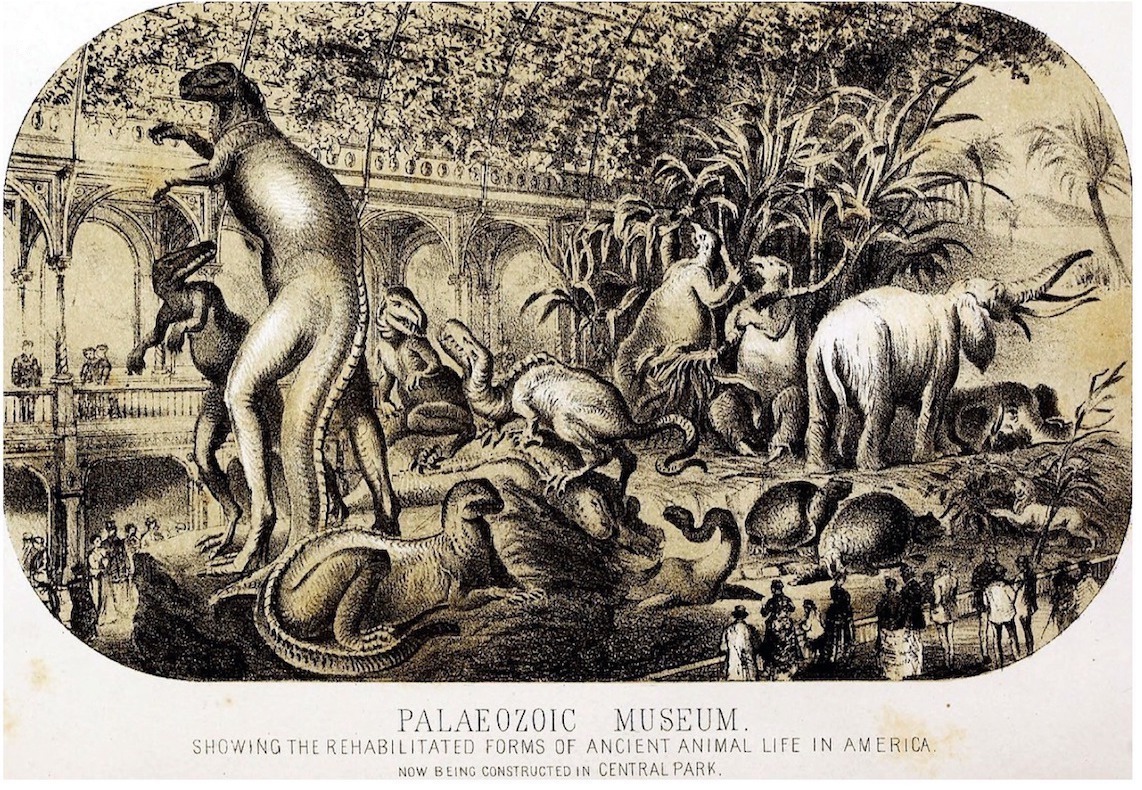

A Paleozoic Museum was once in the works for New York’s Central Park. But in a shocking act of vandalism, the models and casts of dinosaurs and other ancient fauna destined for display there were smashed to bits and buried in 1871.

Notorious politician William “Boss” Tweed was blamed in many accounts. The supposed motives were that evidence of ancient life conflicted with Creationism, and moreover, Tweed wasn’t able to extract kickbacks on the construction.

But in a new paper published earlier in May, art historian Victoria Coules and paleontologist Michael J. Benton, of the University of Bristol, in England, say otherwise.

They say that the man responsible was lawyer Henry Hilton, who served on both the Board of Commissioners of Central Park and the committee to form the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), which stands on Central Park West to this day and is partly beloved for its dinosaur displays.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807–1894). Portrait made in 1870 by Henry Ulke (1821–1910), Washington, DC. Source: Collection 803. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins Album. Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

The English natural history artist working on the dinosaur displays, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, was acclaimed for his similar work for London’s Crystal Palace. Upon arriving in New York in 1868, he was promptly invited by the Board of Commissioners of Central Park (BCCP), then in development, to produce models for the new institution, which was to be designed by the architects of Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. While at work on the new museum, Hawkins would create wildly popular and innovative dinosaur displays at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences.

Hawkins was hard at work at a giant workshop in the Arsenal, in Central Park, when Boss Tweed took over governance of the park, named Hilton treasurer of the parks commission, and canceled the project.

Naturalist Albert S. Bickmore, meanwhile, had recruited worthies such as banker J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt Sr., to a committee to form a natural history museum. The committee also included Hilton, still a member of the BCCP.

“So, just as Hawkins was starting work on the models for his Paleozoic Museum and the foundations were being dug for the building,” the authors pointed out, “the BCCP were also encouraging the formation of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), with its location on or adjacent to the park.”

Plans for the Paleozoic Museum, prepared for the Board of Commissioners of Central Park by consulting architects Olmsted & Vaux. A: front view; B: cross section, with fanciful dragon-like dinosaurs; C: plan view.

Announcing the cancellation of the Paleozoic Museum, the BCCP cited the cost ($7.3 million today), which was to be borne by the city. (AMNH, by contrast, was funded by philanthropic dollars.)

In a May 2, 1871, BCCP meeting, Hilton called for the museum’s assets to be “removed.” The next day, a gang destroyed them all with sledgehammers.

Hawkins quietly moved to New Jersey and worked on paintings of dinosaurs, while sending invoices equaling as much as $500,000 in today’s currency, which Hilton, as treasurer, rejected. Hawkins never brought suit or complained publicly. He may not have wanted to call attention to himself: he was a bigamist, said the authors, having abandoned two wives in England.

And why was Hilton’s reaction against Hawkins so extreme? Perhaps even if Hawkins had been allowed to take his plans to another city, they said, Hilton would have seen it as competition.

What’s more, Hilton was unbalanced, they argued: “the destruction of Hawkins’ New York City dinosaurs was one of many such crazy actions through his life; Hilton was not only bad, but also mad.” He “evidently had a strange relationship with art, heritage and artifacts”—they reported that he separately ordered both a prominent bronze sculpture in Central Park and a whale skeleton at AMNH painted white, damaging both objects. The New York Times wrote: “We are told that he seriously entertained the idea… of covering the whole Park with a coat of white paint.”

He, Tweed, and the rest of their Tammany Hall crew were ultimately exposed as corrupt and driven from power.

Ironically, the Paleozoic Museum probably would not even have been a competitor to AMNH (which, in any event, shows much more than dinosaurs), the authors wrote, but rather more like a theme park, displaying more speculative models.

“From today’s standpoint,” Coules and Benton concluded, “we can suggest that had Hawkins’ Paleozoic Museum been completed, it would have seemed outdated within a decade or so.”

More Trending Stories:

The Art Angle Podcast: James Murdoch on His Vision for Art Basel and the Future of Culture

A Sculpture Depicting King Tut as a Black Man Is Sparking International Outrage