THE DAILY PIC (#1593): Which 19th-century technology managed to freeze and preserve transient moments?

If you answered “the photograph”, you get a B+ (known in my student days as a C). If you answered “the monotype,” you ought to teach the course.

Catching the fascinating show of Edgar Degas monotypes at the Museum of Modern Art in New York – this is its final week – I was struck by how a medium that seems at first sight to be romantic, even precious, is in fact tightly linked to its era’s new tech. The monotype process, which Degas had a hand in perfecting, involves drawing and painting wet ink directly onto a printing plate, then running the plate through a press with paper. In more traditional printing techniques such as engraving, etching and lithography the image is more-or-less permanently marked onto the plate, ready for endless re-inkings and re-printings. With a monotype, however, you’ve got a single shot at a print: Once you’ve transferred your hand-manipulated ink to the paper from the plate, you basically have to start from scratch with new ink and a new image drawn into it.

People often point out that this brings monotypes close to the older, more prestigious techniques of painting and drawing, where a medium is worked directly by the artist’s hand, which leaves an expressive, emotional trace of its passage. According to that reading, monotypes become conservative and nostalgic, linked to Old Masterism and resistant to the mechanical present of an industrial age. I read the Degas prints at MoMA very differently: They may start out with the transient markings made by Degas’s hand, but the technology of printing then fixes that transience into a permanent record of one single instant in its flux. That, as I said at the top of this column, makes the monotype a close analog of Degas’s beloved medium of photography.

Monotypes actually look a great deal like photography, in their suggestive blurrings and range of gray tones. And Degas – deliberately, willfully – uses them to capture photographic effects of instantaneity: Even though Degas was constructing his images in the print shop, not in front of moving subjects, his heads are often caught in mid-turn, or even from behind, and subjects are conceived in snapshot terms.

His many brothel scenes, which he only ever presented in monotypes, feel as though they were captured on the fly by a lens. (I wonder if the images seemed less socially transgressive when they only existed in the single copies permitted by the monotype process, rather than for potentially wide distribution as mass-produced pornography.) His radically abstract landscapes were, he said, inspired by the chaotic view of the countryside glimpsed from a moving train – the kind of uncomposed view most typically seen in photography.

Monotypes even echo what semioticians call the “indexical” qualities of photography, whereby an event leaves a direct trace of its presence. In photography, that “trace” is left on the film by the light bouncing off an object, whereas with the monotype the event that gets traced is the artist’s manipulation of his ink, often leaving that most indexical mark of all, a fingerprint.

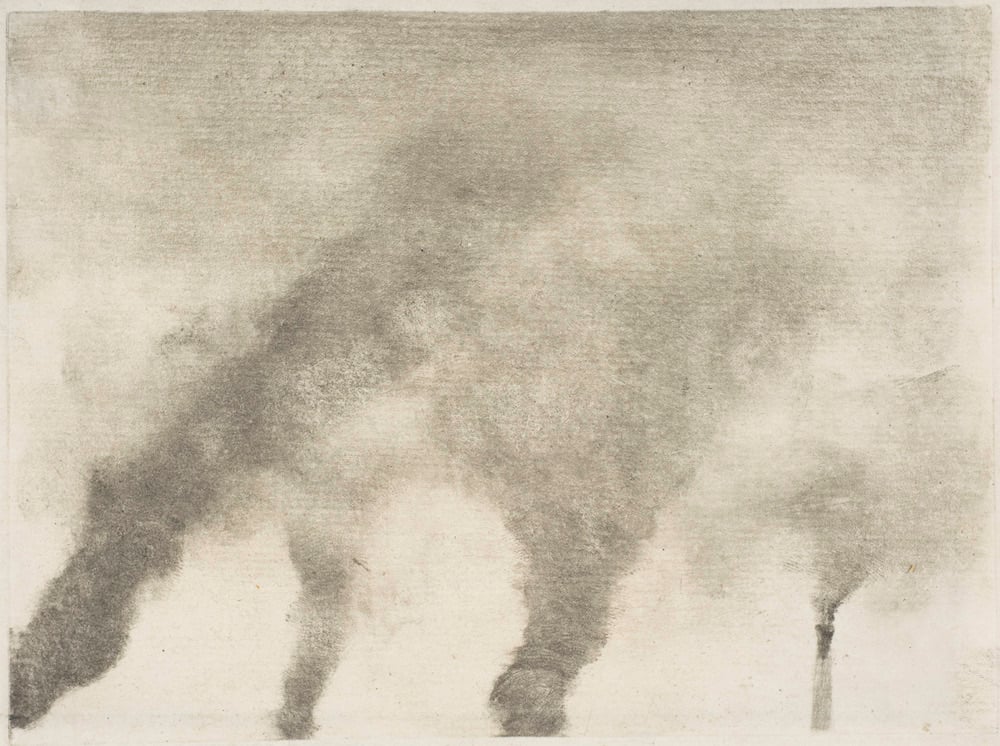

Today’s Pic, titled “Factory Smoke,” from about 1879, provides an almost perfect example of what I’ve been claiming. Its subject, for one thing, is utterly industrial, and Degas renders it using the strange croppings that are trademarks of photography. That industrial subject, moreover, is revealed to us only by an indexical trace, in smoke, of its presence – a trace that the blurred, gray-on-gray monotype process does a perfect job of capturing. And there, at the bottom of one trail of smoke, is the monotype’s signature mark, the sign of how it fixes passing accidents: Degas’s own fingerprint. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1982)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.