The most iconic curatorial moment in “The Milk of Dreams” at this year’s Venice Biennale was the pairing of works by Belkis Ayón and Simone Leigh at the opening of the Arsenale section of the show. Upon entering the first gallery, Simone Leigh’s towering bronze bust of a Black woman with braids adorned with cowrie shells atop a bell-shaped torso/skirt commands awe. Dispersed along the walls that encircle Leigh’s monumental piece are monochrome prints by Cuban printmaker Ayón, which arrest you with the gaze of its central, repeating character. While the piercing eyes of the mythological bodies in Ayón’s works stare intently, Leigh’s sculpture does not have eyes to peer back. It’s as if the ancestors of Jamaican-American Leigh and Afro-Cuban Ayón are silently exchanging sacred knowledge gleaned through transatlantic movement through time and space. This room sets the tone for a show that throughout weaves consequential threads between artists of various generations, regions, and movements.

For myself, one of these important connections happened two rooms later with a wall of seven works by Mexican-American artist Felipe Baeza. The connection of themes of diaspora between Leigh, Ayón, and Baeza feels pertinent: all reckon with truths about gendered subjectivity, particularly when these truths have been lost due to people moving across borders because of various forms of subjugation.

Felipe Baeza, Emerging in difference (2022). © Felipe Baeza, courtesy

Maureen Paley, London and La Biennale di Venezia

Baeza’s crepuscular landscapes of blue and purple allude to the colors of the skies as migrants cross the U.S.-Mexico border at dawn. The deconstructed body parts in Baeza’s works writhe amid foliage, at times transforming into flora itself. In Emerging in Difference (2022), a male figure gazes intently at the viewer while thorny vines, forming the bottom half of a body, root in the land. Beneath the figure’s torso, amid the tangle of plant arms, is a single red hibiscus flower sprouting from a jaw bone. The image poses a solution to dire and fraught circumstances surrounding the queer brown migrant body, faced with the struggle to survive, exist, and be visible: Baeza’s scene of regeneration suggests a survival mechanism, where bodies camouflage into the land.

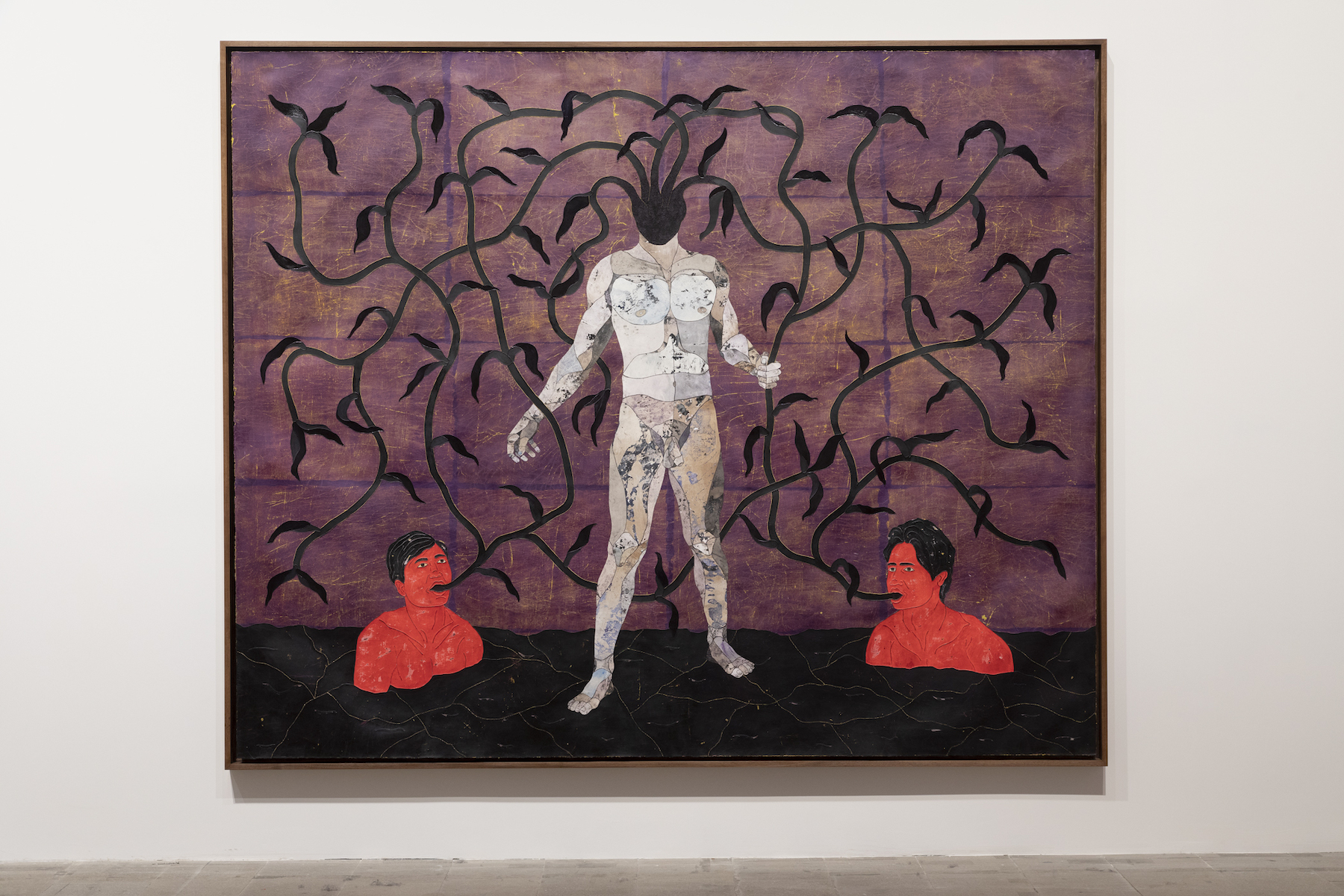

Like Ayón, the 34-year-old Baeza also uses the process of collagraphy—a collage-like process of adhering diverse materials onto a single substrate, creating an embossed, textural surface. The limbs of Baeza’s figures are dissected, scrutinized, while the faces are rapt with expressions of longing. The variously muted colored pieces of the bodies, such as those of the central nude figure in Por caminos ignorados, por hendiduras secretos, por las misteriosas vetas de troncos recien cortados (2020), are sanded and scratched, revealing layers of process. Black vines grow from the figure’s head, making it appear like a human heart. These symbolic veins feed the mouths of two men below, their bright red torsos stuck in a black rock underworld.

Sure, there’s a yearning for place in Baeza’s work. But there is also a yearning for transcendence, for a belonging beyond place. There’s the suggestion that these evanescent bodies are already of the Earth, the land, the natural world, and will forever be in flux. These “fugitive bodies,” as the artist calls them, refer to the constant metamorphic state that a queer brown migrant embodies as they traverse socially constructed borders, whether those imposed by the government or by hegemonic values.

Felipe Baeza, Fragments, refusing totality and wholeness (2021). © Felipe Baeza, courtesy Maureen Paley, London and La Biennale di Venezia.

One of the smaller works in Venice is called Fragments, refusing totality and wholeness (2021). It gives us the head of a brown man emerging from a rocky terrain, breathing a ghost-like bluish lavender spirit from his mouth. The specter’s ectoplasmic gown is embroidered with strings that dangle and sway if you breathe too close to the piece. The slight color gradations and embroidery details in this work demand the viewer’s proximity and activate an intimate moment with the enchanting image.

Like many of the artists in “The Milk of Dreams” who delve into esoteric practices, mythologies, Indigenous epistemologies, or surrealism (but particularly like Ayón), Baeza’s work addresses a psychosocial imbalance in existing as an ‘other.’ Baeza’s landscapes show us a spiritual procession toward conceiving of a reality more in line with fundamental truths, a realm where bodies assimilate into the cactus and soil rather than into the constrictive identity politics wedded to our nationalities or sexual orientations.