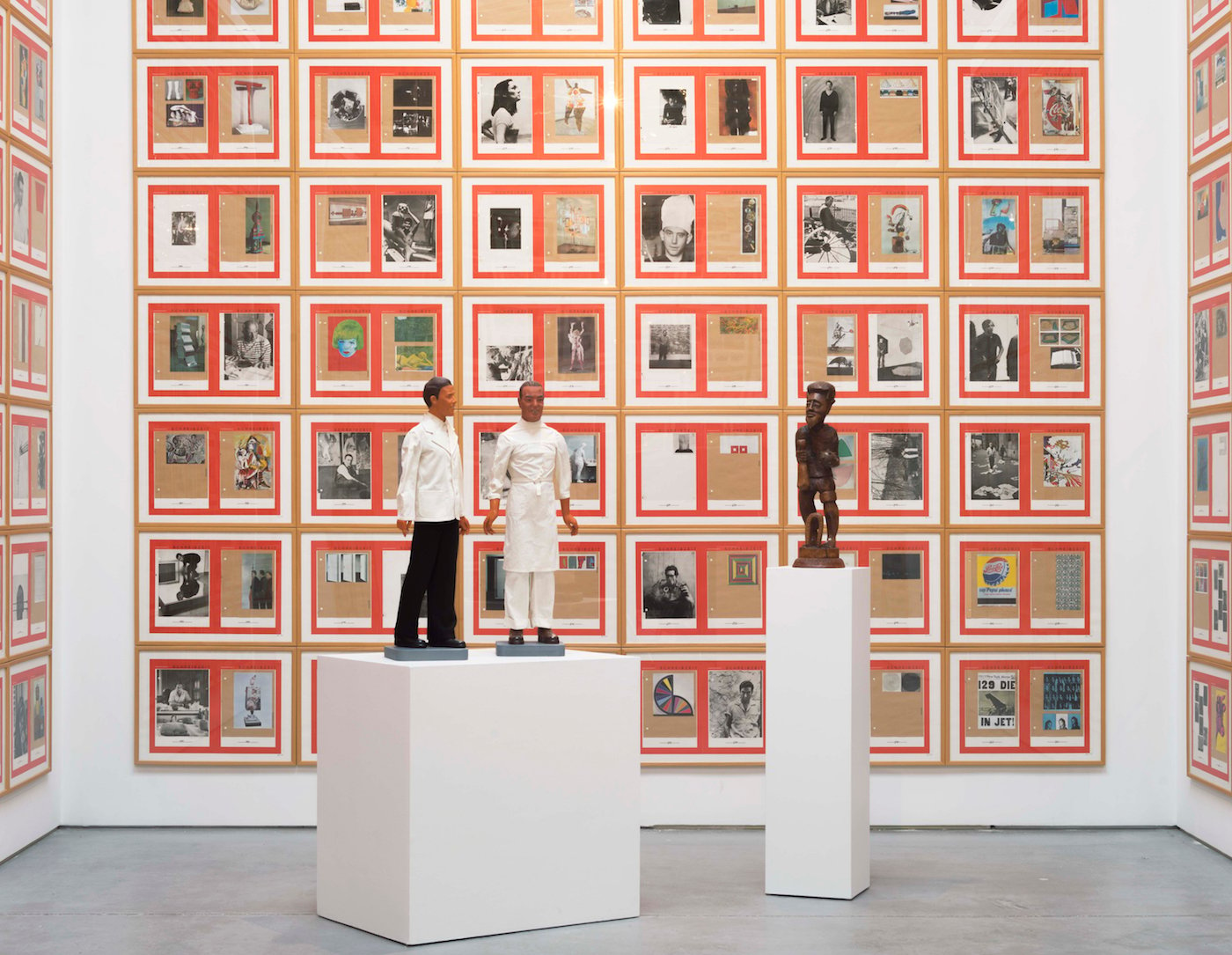

THE DAILY PIC (#1741): Taking in Hanne Darboven’s Cultural History 1880–1983, a piece from the early 1980s now on view at the Dia Art Foundation in New York, is an overwhelming experience. The walls of a huge Dia space are covered, baseboard to rafters, in more than 1,500 framed images. One big series consists of pages derived from an old art catalogue. In another, Darboven collages the same photo of a camera on a tripod next to various period shots of Shirley Temple, Marlene Dietrich and other Hollywood stars. A third suite is built from almost-identical photos of Manhattan doorways – hundreds and hundreds of them. And then there is still suite after suite on top of those. Throughout the show, peculiar found objects sit in corners here and there, and then get repeated in framed photos of themselves on the wall. It is all vastly more than any poor art critic can absorb, or even blink at.

Which is how the installation gets at a vital aspect of Western art that is almost never noticed: A lot even of our greatest objects were not really created to be seen, let alone studied in the way we moderns prefer.

During the Renaissance, when our art traditions took off, sacred pictures were often hung in dark corners of churches where they could never have been seen at all well. (Read period accounts of them, and you realize that people who wrote about pictures could often barely make out what they were writing about.) With secular paintings, a favorite hanging spot was the blank space high above doorways, hardly an aid to lengthy contemplation. Even Michelangelo’s great frescoes up overhead in the Sistine Chapel hardly make looking easy, as anyone who has studied them in situ knows. (The crick in my neck is still there.) That’s why there’s been so much crowing about the new high-res shots that have recently been taken of them.

And now, 500 years after Michelangelo made his (largely invisible) masterwork, our most serious art collectors – especially our most serious art collectors – are perfectly happy to purchase piles and piles of pictures that live in storage and that they may never lay eyes on again.

All of which is evidence in favor of non-visibility as a vital aspect and even virtue of Western art. Our human fascination with images is so great that it matters as much that an image simply exists as that it gets seen and studied. The recording of the world is a virtue in itself, even if that record is never consumed. Putting great art into the world may be an even greater virtue, even if few eyes ever feast on it. The simple fact of its creation is enough. It doesn’t need to be seen to be worthwhile.

Getting back to Darboven at Dia (sorry for the detour) the sheer mass of images she assembles can be read as a testament to the age-old glories of non-visibility. Her images are intriguing enough that they establish their right to exist. And then their quantity foils all our attempts to take their measure. Our “cultural history,” indeed. (Photo by Bill Jacobson, courtesy Dia Art Foundation)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.