This is the second part of a two-part review of “Hans Haacke: All Connected” at the New Museum in New York. The first part can be found here.

For myself, Hans Haacke’s masterpiece is A Breed Apart (1978), his series replicating the look of magazine ads for the then-sturdy British car brand Land Rover. These alternate lush photographs of aspirational automotive ownership with black-and-white images of state violence in South Africa. The copy spotlights the company’s policies of aiding the Apartheid government.

Haacke created the work for a show at Modern Art Oxford. Leyland, Land Rover’s parent company, was a supplier of cars to South Africa, including attack vehicles. Putting pressure on the automaker had long been a strategic focus of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement. Not so far from the museum where the work was shown, the company’s Plant Oxford was a target of political protest and worker organizing.

With justifiable pride, Haacke relates in the label for the work at his current survey how, when he originally showed the work, Anti-Apartheid activists and the museum teamed up to create a poster of the first panel of A Breed Apart that was then distributed to supporters. He adds, without commenting on it or explaining what it means to him, “It was printed by Nuffield Press Ltd., a Leyland subsidiary in Oxford.”

Both Haacke’s museum installation and the more widely distributed graphic played tiny, molecular parts in a far vaster, sustained, decades-long campaign of international solidarity to embarrass and isolate South Africa’s white-supremacist state.

Hans Haacke, A Breed Apart (1978). Image: Ben Davis.

It mainly falls outside of the realm of “institutional critique” as a framework, however. Its target is hardly the art institution, and it’s not a biting-the-hand-that-feeds-you kind of gesture. Rather, its force lies in its strategic use of the art space as a platform from which to hit a nearby target. Like the original Shapolsky et al, actually, it emerges out of a faith that the institution is a meaningful space to occupy, and a site to launch attacks on injustices.

A Matching Dialectical Approach

I began the first part of this review by wondering whether the misremembering of his real-estate exposé work Shapolsky et al as “institutional critique” doesn’t represent some kind of systematic misunderstanding of his career. Reviewing his own writing, you find that the need to use the institutions of art in spite of their compromises is a consistent theme. Thus in 1976, in “The Constituency,” he warns:

Nothing is gained by decrying the daily manipulations of our minds or by retreating into a private world supposedly untouched by it. There is no reason to leave to the corporate state and its public relations mercenaries the service of our sensuous and mental needs, or to allow, by default, the promotion of values that are not in our interest. Given the dialectic [sic] nature of the contemporary petit-bourgeois consciousness industry, its vast resources probably can be put to use against the dominant ideology. This, however, seems to be possible only with a matching dialectical approach and may very well require a running involvement in all the contradictions of the medium and its practitioners.

Given Haacke’s overarching interests, I think his “dialectical approach” could be translated as something like this: Corporations and the wealthy attach themselves to art institutions to give them a veneer of progressivism; that means that the same forces that make institutions prone to neutralizing critical art also make them open to promoting critical art; that’s a contradiction you have to navigate, but you can—and should try—to push that contradiction in order to make meaningful interventions.

Hans Haacke, Oil Painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers (1982). Image: Ben Davis.

In an interview with October in 1984, he was even clearer:

[L]et’s not forget that we are not living in an ideal society. One has to make adjustments to the world as it is. In order to reach a public, in order to insert one’s ideas into the public discourse, one has to enter the institutions where this discourse takes place…

[A]ll in all, it is a messy situation, full of compromises. But I think one has to be pragmatic. Otherwise, one is completely paralyzed. If I had not made adjustments, by now I would be consumed by bitterness and nothing would have been achieved.

Mobil Critique

It is, in this light, less of a scandal than it might appear to some that Haacke does not directly target the New Museum’s own institutional structures in his retrospective. Because he is so associated with highlighting the evils of corporations and unscrupulous wealth, the expectation is logical (and his name bears enough critical weight that the impending arrival of this show gave the museum’s union a powerful talking point when it was fighting over its contract earlier this year). Yet the self-reflexive form of intervention—turning the content of the art into a conversation about the dynamics of the institution where it is shown—is something Haacke has not pursued in an automatic way, always acting with a degree of tactical flexibility and focusing on specific issues that he is engaged with.

Hans Haacke, MetroMobiltan (1985). Image: Ben Davis.

His clunkily named 1985 work MetroMobiltan is one of his clearest and most frequently referenced works tackling the evils of corporate museum patronage. A carved quote on the entablature recreates a line from a Met pamphlet pitching museum sponsorship as good PR to potential funders. At the center is a banner touting a then-recent exhibition of Nigerian artifacts at the Met sponsored by the oil company Mobil. Flanking it are other banners quoting from Mobil’s corporate policies on working with South African Apartheid. The implication is clearly that the company’s sponsorship of art from one African country is meant to whitewash its unsavory doings in another.

Haacke had been doggedly making art targeting Mobil’s Apartheid ties, including through works shown in his 1984 Tate show. Mobil responded with legal action, actually stopping the distribution of that exhibition’s catalogue. MetroMobiltan was made the following year and shown at John Weber gallery in New York.

It was certainly not shown at the Met itself, a fact worth stating given how important ideas of site-specificity have become to the lore of “institutional critique.”

When its example is invoked, leaving the site undefined allows a viewer or critic to either over- or under-estimate the critical charge of the gesture. It overestimates it if the insinuation is that the work was some kind of direct confrontation with the forces of money over art by an artist who occupied a pure purchase outside of any entanglements with that system. It underestimates it if it insinuates a system so tolerant of contradiction that the gesture was meaningless, and not an act requiring some tenacious grit.

Hans Haacke, MetroMobilitan (1985). Image: Ben Davis.

But most importantly: Reading it as being principally about corporate “artwashing” deemphasizes that its most important target was Apartheid!

The work’s museum-style banners hang over a blown-up black-and-white documentary photo of marching black workers in South Africa. Haacke clearly means this device as an allegory of how art is being used to cover exploitation—but the critical interpretation of MetroMobiltan has actually tended to echo this gesture of obscuring, centering its meaning as being about the compromises of art institutions, rather than being about focusing attention on the then-active international boycott campaign.

You might narrate how Haacke’s artwork functions in the following way: Mobil was tapping art to cleanse its image; he saw that this very maneuver opened up a circuit whose energy he could reverse, using the company’s art ties to embarrass it and get publicity for exactly what it was trying to hide.

MetroMobiltan appeared the same year that the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act was first introduced into US Congress. The act would be passed the next year, 1986, punishing trade with South Africa’s white-minority state. Under pressure, in 1989, Mobil Oil quit the South African market, where it had $400 million in assets, an act viewed as a step on the way to toppling Apartheid.

Hans Haacke’s News at the New Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

The Embarrassing Class

Emphasizing that allusion to a sustained movement rooted outside the art sphere is important to me. Without that reference, you get the creeping sense of politics-in-a-bubble.

Remember, the paradox is that Haacke’s discovery of the museum as a political site came at the exact moment when he, through his polls and surveys, identified its social limits—that it was not a space with a universal message or universal audience, but one that was fairly circumscribed.

Haacke would hypothesize that in art, you were speaking to “a rather young audience, financially at ease but not rich, college-educated and flirting rather with the political left than with the right.” He saw that this audience as torn: “This embarrassing and embarrassed class, in doubt about its identity and aspirations and riddled with conflicts and guilt, is the origin of the contemporary innovators and rebels, just as it is the reservoir of those most actively engaged in the preservation of the status quo.”

Even as Haacke had to fight for the place of his charged artwork in the museum against formalist aesthetics, he was becoming aware that to be relevant this art would ultimately need to do more than just flatter the enlightened self-image of its liberal audience.

Recreation of Hans Haacke’s MoMA-Poll at the New Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

“The MoMA Poll was harmless,” he once reflected on the 1970 artwork I described in the previous part of this essay, which used an interactive poll at the Museum of Modern Art to try to make visible visitors’ disapproval of Governor Rockefeller’s stance on Vietnam. “At best it was embarrassing for the museum and its backers and served as a valve for the anger of a surprisingly large portion of the visitors.”

Hans Haacke, Oil Painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers (1982). Image: Ben Davis.

Yet when it came to formal politics, the figures Haacke would come to skewer most prominently—Ronald Reagan (in Oil Painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers) and George H.W. Bush (in Trickle Up and Photo Opportunity) and Jesse Helms (in Helmsboro County, not included here)—would not exactly be sacred cows for an art audience assumed to be “flirting rather with the political left than with the right.”

This is where the historical fact that Haacke’s style of lefty interventionist art finally found some institutional favor in museums and biennials in a period when the right was ascendant is important. It was under Reagan and even more under Bush that “culture wars” politics became a Republican obsession, specifically targeting artists as deviants and menacing public art funding. Haacke’s targets capture just how defensive the climate for art was, reflecting a sense of needing to dig in, to hold the embattled space of culture against rampaging conservative ideology.

Hans Haacke, Photo Opportunity (After the Storm/Walker Evans) (1992). Image: Ben Davis.

In Free Exchange, a 1995 series of dialogues with French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, Haacke would say straight out that one role for political art was to help its audience in “recognizing that they are not alone in what they think,” adding that “preaching to the converted is not, as one says, a total waste of time.”

It’s not—but it’s not without its risks either. In particular, this defensive posture risks a loss of political definition over time, since “politics” becomes defined negatively, by what it is against.

The kiosk for Hans Haacke’s new museum survey. Image: Ben Davis.

For this New Museum show, Haacke offers an updated survey of visitors’ attitudes, administered via touchscreen stations on the fifth floor. One question is about current political thoughts: “When comparing the administration of President Obama with that of Donald Trump, which one represents American values as you understand them?”

But what are “American values”? That is not a radical phrase. A large majority of the world would answer: oligarchy, militarism, grotesque over-consumption.

A question from Hans Haacke’s updated survey for the New Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

Information Warfare

It would be wrong to say, however, that Haacke was unconcerned with escaping the limits of politics in the museum. He tests, over time, a variety of strategies for breaking open the museum frame, from self-critical “institutional critique” to public art. But the most fundamental is: Make the art newsworthy.

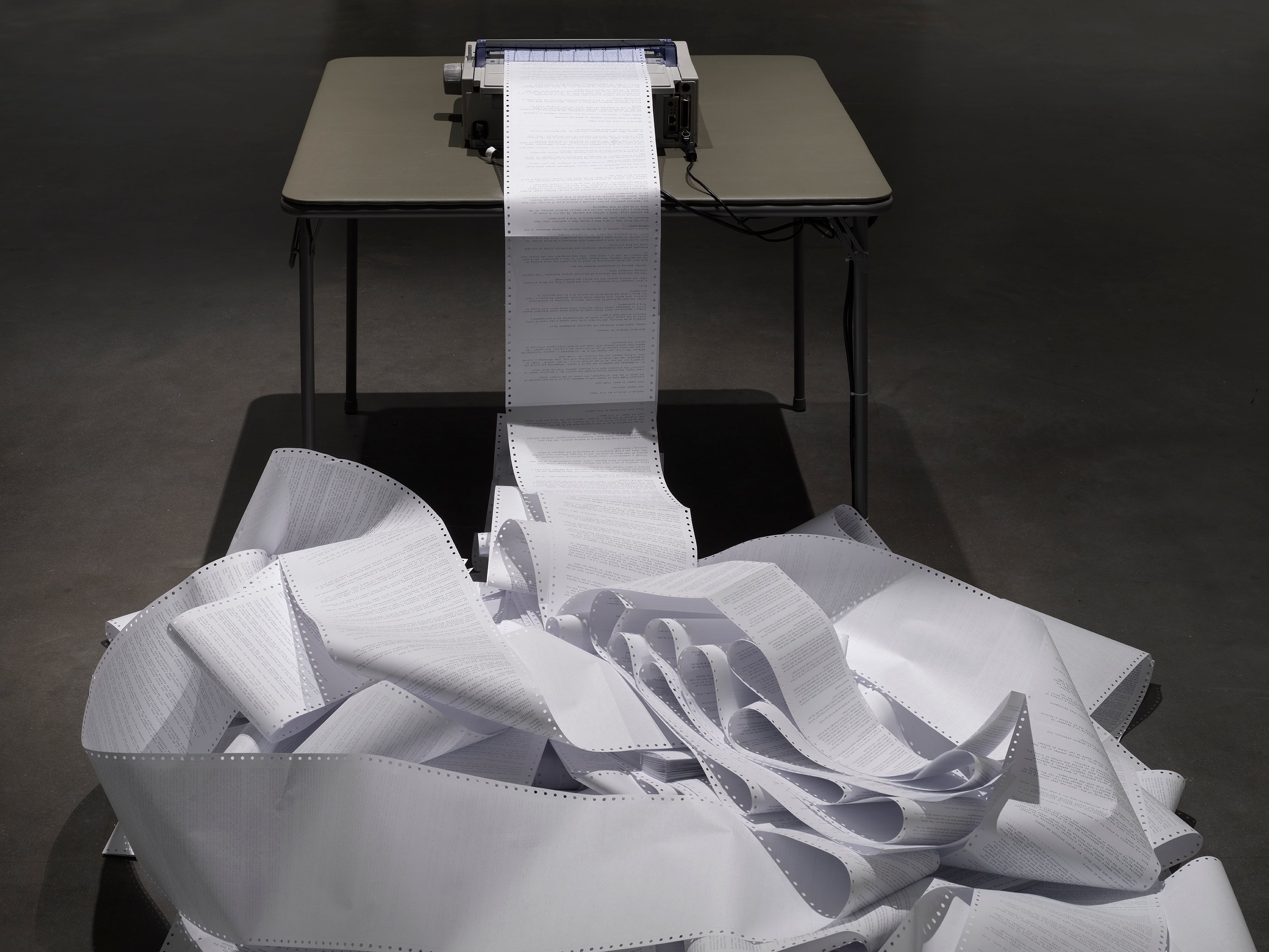

Among the key works in the New Museum show is News (1969-70), originally shown in different forms at “Prospect 69” at the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and the Howard Wise gallery in 1969 and at the Jewish Museum’s “Software” show in 1970. It consisted of a teletype machine, clacking out the day’s news automatically. At the New Museum, the reams of perforated paper from an autonomous printer slowly pile up on the floor in the center of the gallery.

Hans Haacke’s News at the New Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

News is a blunt sculptural enactment of Haacke’s epiphanies in the particularly inflamed moment of late-’60s protest that art needed to interface somehow with the events shaking the world outside of the institution if it were to be relevant. In a way, it’s a conceptual continuation of Condensation Cube, which depended on the difference of climates inside and outside its box. News depends for its effect on the difference in atmospheres inside and outside the museum, the contrast it highlights between the static, timeless atmosphere of art and the urgent, moment-to-moment rhythm of breaking news.

Hans Haacke, Condensation Cube (1963–65). Image: Ben Davis.

One of the things Haacke would learn from his confrontation with the Guggenheim over Shapolsky et al just a few years later was that power lay in reversing this flow: not by bringing news in, but by plugging the art object into news coverage outside.

“[T]here would have been no consequences to speak of had I pulled in my tail and not immediately issued a public statement and assured its widest possible circulation,” he wrote in “Provisional Remarks,” his 1971 reflection on the Guggenheim dust-up. “I thus plugged the affair into the larger environment of the artistically and politically alert public.”

Hans Haacke, Trickle Up (1992). Image: Ben Davis.

As Haacke went on to theorize the conditions of his interventions, the fact that the actual point was tapping into a loop of feedback between the art institution and the media became clearer and clearer. In Free Exchange, he stated bluntly that his style of art “does not work well if the press fails to play its role of amplifier and forum for debate. There has to be a sort of collaboration.”

Detail of Hans Haacke, Trickle Up (1992). Image: Ben Davis.

Some of Haacke’s art actually reads better when you realize that what he is going for is something like a PR stunt for some topical progressive thought. I’m thinking of Trickle Up (1992), a battered couch, evoking the wreckage of working class life, with a pillow embroidered with a phrase from George H.W. Bush extolling the virtues of tax cuts for the rich.

Hans Haacke, The Invisible Hand of the Market (2009). Image: Ben Davis.

Or The Invisible Hand of the Market (2009), made in the wake of the financial crisis, which is a sign hung on the New Museum lobby featuring the titular phrase from Adam Smith, only with a sculpture of a hand waving bye bye where the word “Hand” should be.

Hans Haacke, Make Mar-a-Lago Great Again (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

Or even—the biggest groaner in the show—Make Mar-a-Lago Great Again (2019), a desultory assembly including a screen playing @realdonaldtrump Tweets turned on its side, with signage hawking Trump merch and golf clubs.

“Fun” may not be the first word you think of when you think of this ultra-serious artist. But Haacke’s assessment of the museum audience as being primarily shaped by advertising and entertainment led him to theorize soberly (also in Free Exchange), “It has to be fun to get involved. If it’s annoying, they go somewhere else—and they will be paid more.” The imperative of hacking the spectacle economy explains the slightly expedient character that his work increasingly assumes, formally.

Leaving aside aesthetic merits, there is a pitfall here on the more ideological level: It’s possible that the emphasis on garnering buzz and media subtly comes to displace the value of a reference to organized protest movements, which Haacke’s best work (for me, the anti-Apartheid work) actually did have.

But then the entire period of the ’70s to the 2000s was characterized by left social movements that were retreating, in disarray, at best episodic.

Every Little Bit Helps

If this is sounding very critical, I’d emphasize that that’s the flip side of the fact that Hans Haacke is such an admirable figure. The tactics he has pioneered have opened a path for artists in his wake to engage with society in all kinds of new ways. The issues he has raised have directly inspired some of the thorniest debates in the art sphere today. That’s why this show is an event. Assessing what it has all meant seems important.

In some ways, the modern cycle of protests around museums began with Gulf Labor’s attempts to organize a boycott against the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi to shine a spotlight on the conditions of the largely South Asian guest workers building the nascent institution, starting at the beginning of this decade. Haacke was a member of this coalition.

You can draw a line from one Guggenheim confrontation to another, from 1971 to 2011, with Haacke as a generative connector between the earlier radicalism and today.

Hans Haacke, Gift Horse (2014). Image: Ben Davis.

It’s worth reading artist Naeem Mohaiemen’s text “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Campaign” (Haacke contributed photos to the essay) which tells the story of the unglamorous, years-long labor of artists around the Guggenheim campaign to try to get the museum to pressure the UAE to improve workers rights. In the New Museum catalogue, another member of Gulf Labor, Walid Raad, explains the dynamics:

Hans and everyone else involved were very clear that Gulf Labor was not an artwork. It was a form of advocacy and activism, of sociological, anthropological, and economic research. This advocacy, activism, and research was intended to improve the conditions of thousands of workers building the Louvre and the Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi, and we attempted to enact that change as artists but not through artworks.

That spirit chimes with and amplifies the pragmatic perspective that Haacke’s theorization of his own practice has bequeathed to art (“The art world is not that important,” he told October in 1984). At the same time, looking at Haacke’s legacy seems key now as a precedent for how museum-focused political art has sometimes entered history in ways that de-emphasize and diffuse this perspective.

Hans Haacke, Shapolsky et al Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System as of May 1, 1971 (1971). Image: Ben Davis.

To return, one final time, to the case of Shapolsky et al, and the fact that it gets misremembered as “institutional critique”: Have you ever wondered what actually became of the target of that work?

The artwork, it turns out, did some good. The Shapolskys’ real estate empire had been investigated by journalists for decades already, but the controversy put a new spotlight on him. According to Julia Bryan-Wilson, the Village Voice would mention Haacke’s work in declaring Shapolsky one of the city’s worst slumlords. The NYPD even called on the artist to look at his research for another real-estate investigation piece censored from the Guggenheim show, Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, because they were investigating Goldman for mafia ties.

But the Shapolskys went on to what appears to be a long career in global property. “Is he flipping? Is he buying? He’s an in-and-out kind of guy,” a broker told the Real Deal of Arthur Shapolsky, son of the Sam Shapolsky whose name appears in Shapolsky et al, just a few years ago.

As for Sol Goldman, he was hit harder by the downturn in 1973-’74 than he was by Haacke, but died in 1987 as New York’s largest private landlord.

Detail of Hans Haacke, Shapolsky et al Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System as of May 1, 1971 (1971). Image: Ben Davis.

This is not to say that Haacke’s work is valueless because it didn’t spark The Revolution. It’s just to say that the way the tale gets told—reliving the face-off between artist and institution, as if that were the point—tends to bracket out the actual referent and thereby invert the focus. Shining a spotlight on racist real-estate practices appears in history as merely the pretext for an art controversy, rather than the art controversy being used as a pretext to shine a light on any kind of movement against racist real-estate practices.

You are left with an aura of artistic heroism, when everything about what actually happened tells you that this misjudges the scandal’s modest impact outside the institution. The bubble of the museum audience’s self-importance reappears right at the moment where you believe you are breaking out of it, as if you were waking up from a dream into another dream.

Hans Haacke, We (all) are the people on the front of the New Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

Extracting a single strategy from Haacke’s body of work is tough. He has woven between different forms of engagement. What I’m trying to emphasize is how his own example contains the resources for criticizing some of the ways that “institutional critique” has entered into history.

“Of course, I don’t believe that artists really wield any significant power,” Haacke once told Jeanne Siegel. “At best, one can focus attention.” The line, quoted in his New York Times profile leading up to this show, is striking from a figure considered the very paradigm of the outspoken, engaged artist.

So I went and looked it up. Haacke continues: “But every little bit helps. In concert with other people’s activities outside the art scene, maybe the social climate of society can be changed.”

The pessimism about what the art context means on its own is the flip side of being able to hold onto a cautious optimism that it can actually be important to occupy. Some tether to “activities outside the art scene” is what makes this hope plausible. That’s hard-won wisdom that I take from him.