Go hunting the web for the origin of the familiar “Valentine’s heart” shape in art, and you will find a lot of speculation but few definite answers.

Does the heart shape suggest the leaf of the silphium plant? Or does it hint at testicles? Or buttocks, breasts, or a vulva—or all of these together, rolled into one super-sexual innuendo?

Was the scalloped heart shape, as the neurosurgeon and author Pierre Vinken once suggested, an attempt by late medieval artists to “correct” the newly observed anatomical heart to match Aristotle’s erroneous description of a three-chambered heart? Or, as Martin Kemp suggests in his book Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon, is it actually just an honest try at capturing the real, bulgy muscle (the “lack of resemblance” between symbol and organ, Kemp says, “is considerably overplayed”)?

In European art, the heart symbol seems to have assumed the now-familiar shape sometime in the 15th century. Before that, the heart was depicted as looking like a pinecone, a conception evidently based on the authority of the Greek physician Galen.

But the first artistic depiction of someone giving their heart to their beloved as a symbol of love came earlier.

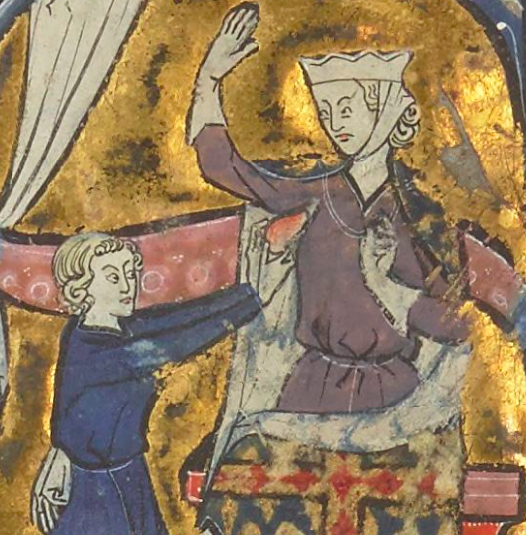

An image mentioned often in the history of heart iconography is an illustration (above) from the 13th-century French manuscript known as the Roman de la poire (Romance of the Pear), by the relatively obscure poet Thibaut. Vinken dubbed this image the “first illustration of a heart outside the anatomical literature.” (Superfans of French medieval literature can see the entire manuscript at the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.)

Cover and opening page of Roman de la poire. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

And it’s a weird one! In keeping with the wackiness of French allegorical poetry, the kneeling figure is not the longing lover himself, but “Douz Regart” (translation: Sweet Look), a personification of the lover’s enamored gaze. The kneeling Douz Regart has been tasked with delivering the lover’s heart (which is pre-heart shaped) to the lady to show his desire. The image, in other words, is a symbolic depiction of “making eyes” at someone.

In a way, you can also see it as a distant precognition of the idea of expressing your love via Valentine, with the kneeling figure as the messenger and the literal heart as the card.

The full page featuring the gift of the heart from Roman de la poire. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

You’ll notice that the vignette is nested within a huge “S.” In the Roman de la poire, the decorative capitals have another special function, explained in Ardis Butterfield’s Poetry and Music in Medieval France. The scheme is wonderfully elaborate, and so worth quoting at length:

Sixteen of [the poem’s] twenty refrains form an acrostic from their initial letters which spells out the name of the lady, AN[G]NES, the name of the poet-lover, TIVAUT, and finally the word AMORS. Many allusions to the acrostic are made in the text: for example it is coyly pointed out that the lady’s name and Love itself both begin and end with the same letters, ‘A’ and ‘S’, and that both lovers’ names have six letters. The two names are spelt out again in riddling form in the narrative (lines 1795-1820 and 2724-43) ensuring that the acrostic exists both horizontally and vertically…

[T]he refrains are themselves messages, exchanged between allegorical representatives of Love and the lady such as Beauté [Beauty] and Loyauté [Loyalty], in such a way that the lover’s greeting makes up the initials of her name, her messengers make up the initials of his name, and both together (appropriately enough) make ‘AMORS’. The acrostic both generates and predetermines the whole work: once the lady completes the final ‘S’ of ‘AMORS’, in the refrain Soutenez moi, li max d’amors m’ocit [Sustain me, the pains of love are killing me], the book comes to a swift conclusion.

Which just goes to show you that contemporary Valentine’s Day card writers really, really need to step up their game if they want to keep up with art history.