In March, an Idaho state college sparked a media firestorm when it censored three artists’ works that dealt with the topic of abortion. The school said it was concerned the artworks could be interpreted as promoting abortion, which would violate the state’s No Public Funds for Abortion Act, passed in 2021. After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade the next year, Idaho enacted a complete ban on abortions

Now, the exhibition, titled “Unconditional Care: Listening to People’s Health Needs,” is finally going on view in its entirety, thanks to the Rochester Contemporary Art Center in Western New York.

Rather than being a show “about” abortion, it attempts to divorce health care from religion and politics, seeking to foster empathy through the work of 12 artists who share personal experiences with pressing medical issues—including abortion.

“Rochester Contemporary Art Center [RoCo] has a long history of exhibiting artists who are addressing important issues through their work. Our organization, like others founded in the late ’70s, came of age as the so-called ‘culture wars’ threatened creative freedom and support for artists,” director Bleu Cease told Artnet News in an email. “The fact that this exhibition was censored in its first iteration only heightens my and RoCo’s commitment to support the artists and the curatorial vision.”

School officials at the original venue, the Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts and History, pulled the work of three artists: Katrina Majkut, who was also the exhibition’s curator, Michelle Hartney, and Lydia Nobles.

Artwork by Michelle Hartney that was removed from “Unconditional Care” at Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts & History, in Idaho. Image courtesy Michelle Hartney.

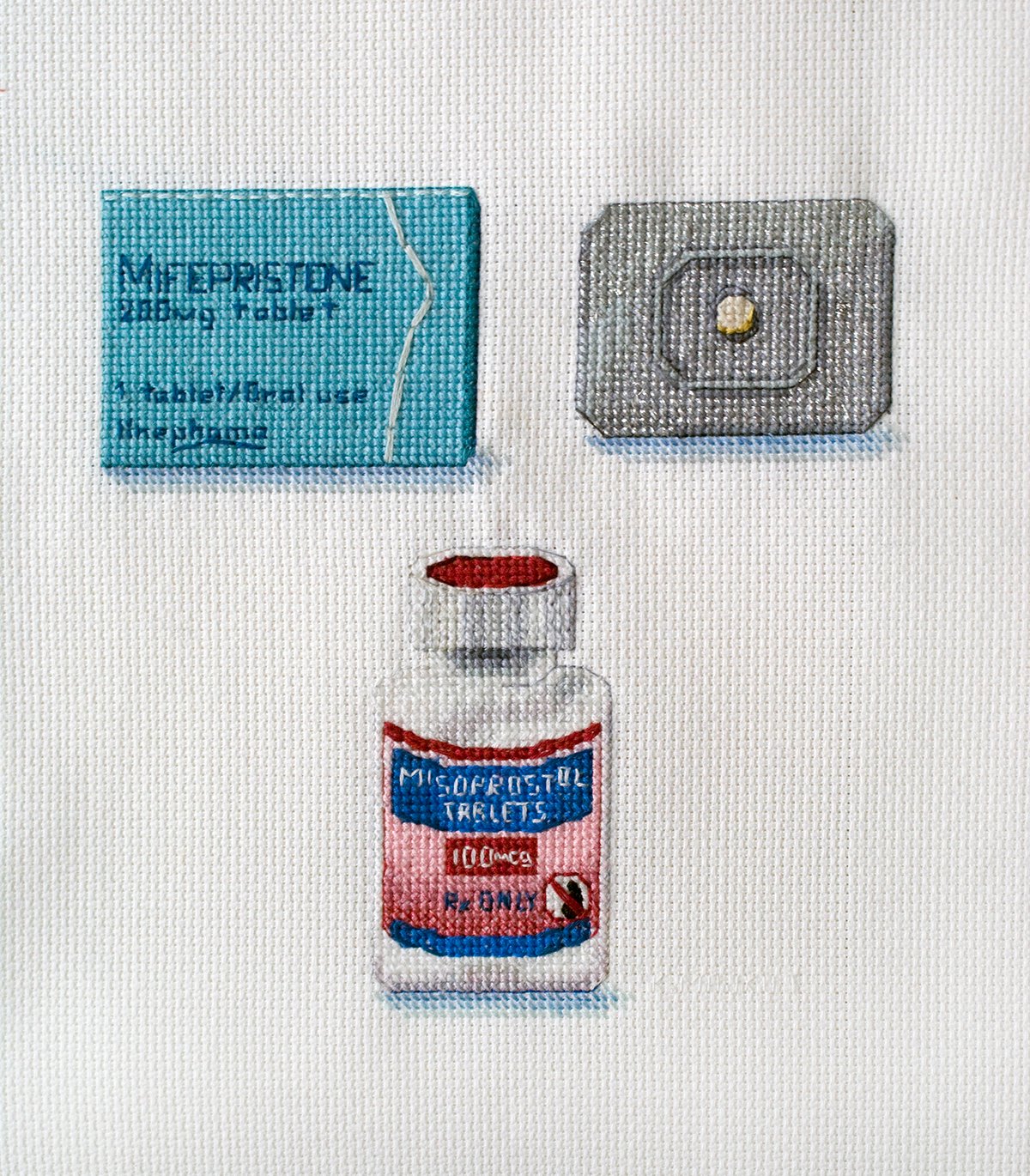

Majkut’s piece, Medical Abortion (2015), is a simple cross stitch depicting bottles of mifepristone and misoprostol, which if taken together will induce miscarriage. Hartney’s artwork is also textile based, part of her communally created piece Unplanned Parenthood, featuring embroidered handwritten letters, originally written in the 1920s by a woman hoping to get information about birth control from Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood. Nobles, meanwhile, had intended to show three documentary videos from her series “As I Sit Waiting,” featuring matter-of-fact interviews with women describing what their abortion procedures were like.

None of the artists believe that their work helped “promote” or “counsel in favor of” abortions—the wording of the state law that triggered the censorship.

“My piece is a word-for-word copy of a historical document,” Hartney told Artnet News. “The letter writer referred to having had two abortions, but the way it was written was almost like ‘I don’t want to go through this again, so how do I prevent pregnancy?'”

Nobles, who had an abortion in 2018, specifically made her series to fill what she saw as a gap in videos available online about the subject that did not have a political or religious agenda. (Work from the series will also be on view next month at New York’s Spring Break Art Show.)

Stills from Lydia Nobles’s documentary series “As I Sit Waiting,” that were removed from the show ‘Unconditional Care’ at Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts & History in Idaho. Image courtesy Lydia Nobles.

“When I approached my project, I really wanted to make sure that the stories were almost kind of boring, that they were stream of consciousness,” Nobles told Artnet News. “But when we layer all these political and moral beliefs onto a medical procedure, it really blurs the information that people need, which is just what it was like in the waiting room, and what was it like in the exam room and during the procedure.”

Majkut took a similar approach in presenting the subject of abortion purely as health care, rather than as a feminist issue.

“I’ve always tried to be bipartisan and to approach things from a neutral and informative and fact-based place,” she told Artnet News. “It’s a still life—I don’t insert my opinion into it.”

The accompanying wall text, which explained the medical efficacy of the medical abortion pill and outlined Idaho’s abortion laws, was also censored. “They wouldn’t even allow that, a reiteration of their own laws—which is shocking within an academic setting.”

The fact that the school would not allow the exhibition to include fact-based explanations of state law—or the term “post-Roe,” referring to the historic overturn of national abortion rights—is a major point of concern for free speech advocates.

“It shows the damage inflicted by cowardly administrators and sweeping interpretations of poorly drafted state statutes that are seemingly designed to chill expressive rights,” Will Creeley, legal director of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), told Artnet News.

“We’ve been warning Idaho schools about the threat to free speech here for a while. Ever since the law was passed, we’ve been encouraging them to stand up for the speech rights of their students and faculty. To have the the art gallery buckle so quickly was really disappointing,” he added.

Nobles believes that by censoring the exhibition, the college actually brought more attention to the artwork it was hoping to silence: “Inadvertently, they just strengthened the impact of our work and the exhibition as a whole.”

But despite widespread media coverage decrying the exhibition’s censorship, the show received little to no support on campus.

“The most chilling part for me is the way it silenced the professors and the students on the campus of Lewis Clark, because nobody would talk to us,” Hartney said. “The student newspaper would not even speak to us because they were afraid of losing their funding.”

FIRE and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) considered taking legal action on behalf of the artists, but ultimately declined to pursue the case. The loan agreements for all of the artworks included a clause that gave the school the final say on what would be exhibited. The concern was that if the case in favor of freedom of speech wasn’t strong enough, a ruling in favor of the college could pave the way for even more restrictive interpretations of the law.

But the ACLU is still fighting against the law in another way, filing a lawsuit earlier this month with six Idaho professors and two teachers’ unions, contending that the act robs professors of their First Amendment right to academic speech.

The lawsuit attacks the law as unconstitutionally vague, in that it forces universities to guess what speech could be considered a violation—and the law’s penalties are harsh, with those who break it facing up to 14 years imprisonment, in addition to termination of employment.

“I don’t think that the college’s response [to the exhibition] was necessarily an overly strict interpretation of the law,” Scarlett Kim, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU, told Artnet News in an email. “The prohibition against promoting or counseling in favor of abortion is highly expansive and lends itself to subjective interpretation.”

For now, the artists of “Unconditional Care” are excited to finally have the opportunity to showcase their work uncensored, with reproductive health care in conversation with other medical issues including cancer, maternal mortality, sexual assault, disability, and gun violence.

“In a world where health is entwined with politics, religion, and misinformation, this project serves as a call for empathy, understanding, and action,” Cease from RoCo said. “The artists reveal the complexities—often through their own lived experiences—of navigating health within America’s systems.”

“Unconditional Care: Listening to People’s Health Needs” will be on view at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center, Main Gallery, 137 East Avenue, Rochester, New York, September 1–22, 2023.