I have seen the future, and it is an ordinary egg.

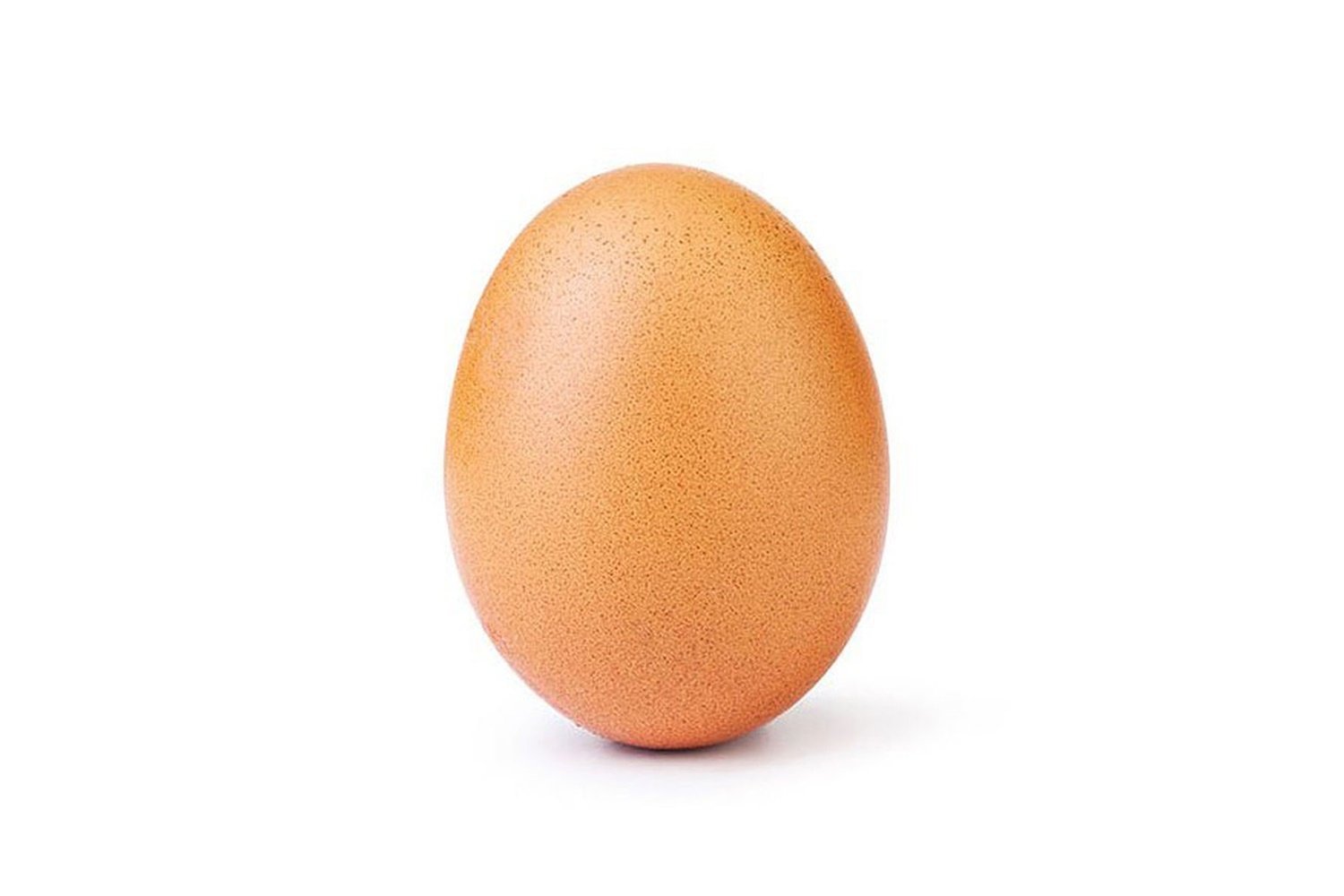

I speak, of course, of @world_record_egg, the mega-viral Instagram account that has rocketed into the record books by posting a single, unspectacular image of a speckled brown egg, becoming in 10 days the most-liked image of all time. You probably don’t need me to tell you about it: More than 42 million people have taken part in this craze. It’s mainstream news.

You can roll your eyes and say, great, the world is falling apart and we are talking about an egg. Or you could say that we’re talking about an egg because the world is falling apart. It’s bleak out there, and the egg is a feel-good story, a kind of social media rags-to-riches tale.

The caption for the one-and-only post from @world_record_egg was: “Let’s set a world record together and get the most liked post on Instagram. Beating the current world record held by Kylie Jenner (18 million)! We got this ?.”

Framed as a competition with Jenner, you can see what kind of hive-mind energy it tapped into. It’s as if the absurdity of collectively making a picture of an egg the most-liked Instagram post of all time mirrors how absurdly much space Jenner and the Instagram elite take up in the public mind.

Suddenly, the Little Egg That Could becomes a kind of collective self-portrait of how inescapably defined we are by social-media competition—but also how definitely small and anonymous the average person feels within these networks.

Perhaps this thesis—“the egg is us!”—is a bit overcooked? These kinds of frenzies come and go, that’s their nature. The egg will soon go the way of the “Damn Daniel!” kid.

But look, the viral fame of this ovular mega-star heralds broader shifts that have been incubating in the space between art and fame and everyday life.

Lot 0038 from the Social Media Memorabilia Auction House. Image courtesy SMMAH.

Last year, a Brooklyn design firm, Talmor & Talmor & Talmor, launched the Social Media Memorabilia Auction House, which purported to sell items worn or used by star Instagrammers in some of their most-liked posts. So you can buy a bowtie, collars, and cuffs once sported by mega-bro Dan Bilzerian (@danbilzerian) at a starting bid of $4,700. The bidding for a set of white leggings that say “HARDCORE”—glimpsed in a post by Colombian model and fitness influencer Anllela Sagra (@anllela_sagra) that almost 32,000 people liked—starts at $6,500. Of this latter lot, the SMMAH catalogue entry says the leggings “can be seen as a metaphor for mental toughness, and empowerment.”

Sadly for Bilzerian and Sagra fans, the auction is a joke, a bit of deadpan commentary on the strange, fetishized accent that falls on ordinary objects when influencer marketing slowly takes over the mental space. Still, fictional or no, the Social Media Memorabilia Auction House probably does reflect something about the future, Black Mirror-style. If some entrepreneur is not already planning such a platform for real, it’s a missed opportunity.

Lot 0008 from the Social Media Memorabilia Auction House. Image courtesy SMMAH.

If you are an observer of art, what this shift from the everyday to the revered inevitably reminds you of is classic Conceptual art. There’s a connection between an ordinary egg becoming an up-with-people symbol and Marcel Duchamp’s recontextualization of a urinal as a joke about fine-art sculpture, or Andy Warhol’s recreation of Brillo Boxes as riffs on consumerism, or Yoko Ono’s offering of a Granny Smith apple as a reflection on mortality, right?

Yoko Ono, Apple (1966). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

(With the Social Media Memorabilia Auction House in the background, it’s worth saying as a side note that there’s a story to be told about the parallel between the rise of Conceptual art and the rise of celebrity memorabilia. The history lines up: In 1972, Lucy Lippard published Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object 1966 to 1972, charting the emergence of Conceptualism as a dominant strand of contemporary practice. Meanwhile, the MGM Studios Auction of 1970, which included, among other things, the trench coat Clark Gable wore in several films, was considered a landmark event, ratifying a new category of collectible object.)

The Instagram egg’s heartwarming success was almost immediately followed by speculation that it was a viral marketing stunt, with the promise of a mysterious phase two for @world_record_egg. #EggGang merch was immediately a thing. ReCode started to calculate how much money the egg could get if it did sponsored posts, with experts estimating that the space was worth anywhere from $250,000 to “close to a million dollars.” That’s an awful lot of value appearing out of nowhere, all thanks to the magic of social context.

A photo of an egg, the most liked post on the Instagram, is seen on a smart phone in Ankara, Turkey on January 14, 2019. Photo by Ali Balikci/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

It’s funny: A complaint you constantly hear about Instagram is that the world it offers is too pretty, too artificial, too filtered—in short, too aestheticized. But the egg seems to suggest the opposite too: a powerful anti-aesthetic current at play. It suggests that the very same space has also given birth to something like an intuitive “people’s conceptualism.”

You could definitely say that a world where an ordinary egg is our biggest star is a world where the distinction between life and art has become almost totally scrambled.