Italy and France have resolved a months-long political stalemate that threatened to scuttle the Louvre’s plan to present an ambitious exhibition of works by Leonardo da Vinci to mark the 500th anniversary of the master’s death.

France’s culture minister Franck Riester and his Italian counterpart, Alberto Bonisoli from Italy’s Eurosceptic right-wing party League, met on February 28 in Milan to discuss, among other issues, the hot-button question of whether Italy would loan its many significant Leonardos to France. The meeting coincided with a thaw in broader political tensions between Italy and France, which had been described as the two countries’ most serious diplomatic dispute since World War II.

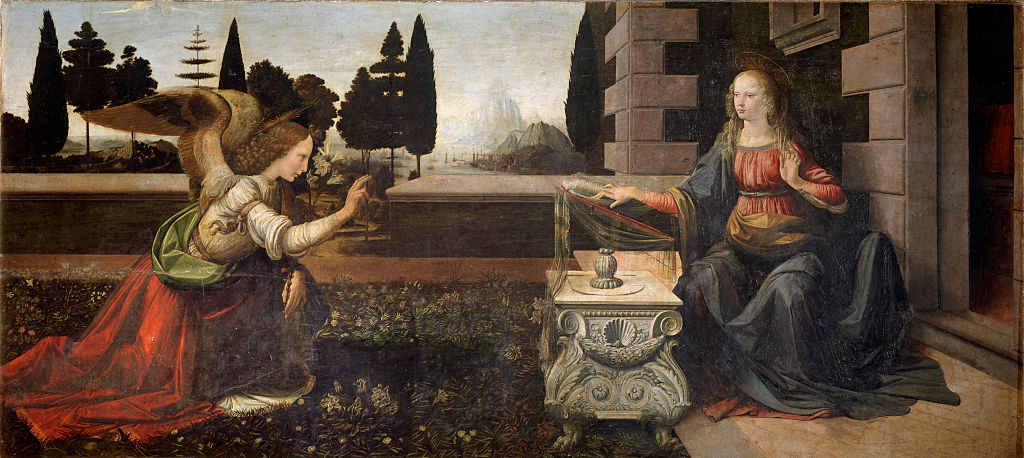

Now, both nations have confirmed that, despite earlier reports, the artworks in question will be exchanged for the Louvre’s landmark Leonardo da Vinci show in October, which has been a decade in the making. In turn, France will loan works to Italy for an exhibition dedicated to another Renaissance master, Raphael, in 2020, timed to commemorate 500 years since his death in 1520.

“Italy and France are two of the world’s cultural superpowers and we must definitely have a dialogue,” Bonisoli said after the meeting, according to the Financial Times. “We are very happy that France should celebrate the greatness of Leonardo—an Italian genius also appreciated by [France’s] King Francis I at whose court the artist, originally from Vinci, spent the last years of his life.”

The months of rising tensions began last November, after Bonisoli’s undersecretary Lucia Borgonzoni vocally backtracked on a previously agreed-upon loan between the countries that would have seen most of the artist’s 17 known paintings, a large array of drawings, and a small yet important group of sculptures come together at the Louvre. In keeping with the League’s “Italians First” agenda, Borgonzoni had told Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera that fulfilling France’s request would “put Italy on the margins of a major cultural event.”

The two European nations are inextricably linked in Leonardo’s history: the master was born in Tuscany in 1452 and died in France, in the province of Touraine, in 1519. But culture in general—and Leonardo da Vinci in particular—have become a proxy for the larger political tensions at play between Italy and France ahead of the European parliamentary vote this May, where right-wing nationalists are expected to make gains.

The pro-European Union president of France, Emmanuel Macron, recently reinstalled the French ambassador to Italy after he removed him last month due to perceived Italian meddling in French domestic politics. (Italian politician Luigi Di Maio of the right-wing Five Star movement met with anti-Macron yellow vest protesters seeking to run for European parliament.)

For now, the diplomatic drama on both the political and cultural fronts seems to have quieted. Macron said on Sunday that he plans to celebrate the anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death alongside Italian president Sergio Mattarella in Paris on May 2nd. Italy’s culture minister Bonisoli said Italy was “happy that France can celebrate Leonardo’s genius,” whose heritage, he says, is “not only Italian but European and universal.” He assured the press that the full list of Leonardo works to be lent to France would soon be confirmed.