Head Banging at FIAC

I was asked why I bothered to incessantly visit art fairs, which according to my social media inquisitor were “so over” and whether I was paid for the pleasure (how did we come to experience before Facebook and Instagram?). Well, actually not such a bad question, but alas I have to make a living art dealing and in so doing, I need to get out and about as much as possible or it simply won’t happen—I work alone in my garage in London. Scribing doesn’t cover more than a night or two of artificially inflated hotel rates, the global norm during big events. Sorry for the potty talk (and toilet humor to follow), but no matter the country why do flushers always stick and require a jiggle?

Beyond that, unlike a certain presidential nominee, I am way more democratic by nature—seeing art in any context is good enough for me: studios, museums, galleries, auctions or fairs—what do I care? For better or worse, art fairs have a radioactive shelf life, they aren’t going anywhere. Admittedly, four walls are better than three to see an exhibit but I relish the opportunity to take in so much, so handily, even if the ubiquity of a group of market affirming fair-artists is unavoidable; it’s a souk, after all, and there is an inescapable orthodoxy.

Though I can’t vouch for the cost to profit ratio for participants (only the organizers consistently prosper, of that I am assured) there is usually something unexpected or new (to me) to learn and the people factor alone—intel and gossip on the buy/sell side of things—is worth the trip every time. And opportunity is always afoot.

Katherine Bernhardt. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain (FIAC), launched in Paris in 1974, is held in the breathtaking Grand Palais, which itself was inaugurated in 1900. A better atmosphere to see an inconsistent mishmash of art doesn’t exist. In the taxi from the airport I was instructed to shut the window or face carjackers before I witnessed a violent alternation in the street involving someone’s head being smashed against a concrete wall.

Despite this, the people I encountered seemed a little less recalcitrant than in the past, maybe softened after the recent terroristic calamities. Achingly beautiful and economically stressed with more banks than money, Paris is not a city to move quickly through; the word traffic connotes eventual movement, but it’s far stiller—I was mentally honking because for some reason they don’t.

Before I jump in, like in a religious service, there are some general announcements to be addressed (I’m monotheistic, a strict believer in one personal and transcendent art form). Did you hear the one about the $45 million Mark Grotjahn triptych that sold to Yusaku Maezawa, buyer of Adam Lindemann’s $57.3 million Basquiat at auction last spring, who you must follow on Instagram for his unabashed material enthusiasms alone? It’s true. Pick an artist, any artist, and for that much you can have an example above your bed, a very good piece at that.

I’ve been told by those involved that even people with their names on buildings have been prone to resell Grotjahn (often within a year or two) for no other reason than that they can—for ten times the initial purchase price. I’d wager that greed exceeds sex as the least likely human impulse to repress. The worst is that the transgressors have been known to come back to the galleries unapologetically expecting more of the same with no compunction.

Still in Los Angeles where Grotjahn resides, an unrelated lawsuit is raging its way through the appeals courts, Chang-Mathieu v. Larner, involving art advisors at each other’s throats in the most untoward terms from a good transaction gone bad, involving a garbage bag—the artwork at the core of the clash—and an anti-SLAPP motion (read for yourself, who could make this up?) including this colorful exchange: “You are gross. And if I was a man I would fucken break your face. I’m a minute. Every dealer will be cc’d to this e-mail.”

Being a woman of her word (in this lawsuit), she indeed copied in other dealers. Perhaps she should run for president. I know what you’re thinking but too late. HBO is already in the midst of turning the art market into a series. Of particular art historical significance is this gem: the first time “art flipper” has been officially addressed in a court of law and though shy of a definitive definition I am happy to clarify, especially in this art economy, that a flip needn’t necessarily entail a profit:

There appears to be some dispute on appeal as to what the phrase “art flipper” means. But no one defines it and no one directs us to an appropriate definition of that phrase. Larner claims that he did not “flip” the piece because he did not sell it to reap a profit. But he does not offer us any legal or evidentiary authority to support his proposition that in order for the sale of a piece of art to constitute a “flip,” the seller must garner a profit.

It Wasn’t All Commercial Fare

Patrick Seguin, who is among the world’s leading furniture and architecture dealers, hosted a party and pop-up prior to the onset of the fair for New York’s Karma gallery. Here was the art world as few have the opportunity to observe: a buzzing, tightly knit community united in camaraderie despite the bare knuckled, zero-sum economic ring they professionally coexist in. Albeit an arena, in the instance of Patrick’s apartment, with an amazing degree of connoisseurship expressed in mid-century furniture and contemporary art, wow. Gallerists are the unsung aesthetic superheroes perpetuating the art market system, a force greater than the sum of its parts.

Art Basel’s Marc Spiegler with a work by Urs Fischer at Sadie Coles’s booth at FIAC. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The Karma gig was an encyclopedic drawing show from the 1950s to the present based on a Parisian publisher of exotic and avant-garde books. Highlights included rough and raunchy Lee Lozano works from 1962 at $50,000-$60,000 and the syrupy 2007 Ken Price watercolor of an intestinal looking sculpture on a pedestal in a generic architectural setting that Matthew Marks disappointingly shot me down from buying for $25,000. Ostensibly, Matthew “didn’t want to sell to a dealer,” but in this universe who knows?

It wasn’t all commercial fare; I also managed to hit the Palais de Tokyo and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris featuring Tino Sehgal at the former, and Bernard Buffet and Carl Andre at the latter. Sehgal’s retrospective entailed hiring 350 actors to star in the three-month run but no supporting reference materials to expound on the often frenetic and fragmented performances that border on disconcerting and at times are downright frightening.

In 2012, I wrote an article entitled: The Value of Nothing: the Selling of Sehgal commenting on the fact that the artist, whether privately or to an institution (where he’s embraced), will sell only an oral agreement in front of a notary with a few witnesses and the right to show the work under what can only be described as stringent conditions. Sehgal’s art is never to be photographed, re-enacted for less than a specified period with specially trained participants, or documented by receipt, contract or certificate. And these works can only be resold under acceptance of the conditions. Oh please.

The actors at the Palais de Tokyo were aged from eight to 80 and particularly unsettling are the kids who resemble casting rejects from the film Village of the Damned where a small town’s women give birth to unfriendly alien children posing as humans. They pepper you with questions such as is life an enigma, how do you describe progress and is it evolutionary. The takeaway was a feeling of annoyance like being the subject of one of my articles. The best of the lot was a pitch-dark room featuring chanting dancers as euphoric as they are fear-provoking. I walked with my arm extended in a defensive posture against any unwanted touching, perhaps stemming from when I was mugged at knifepoint in a London gallery 16 years ago.

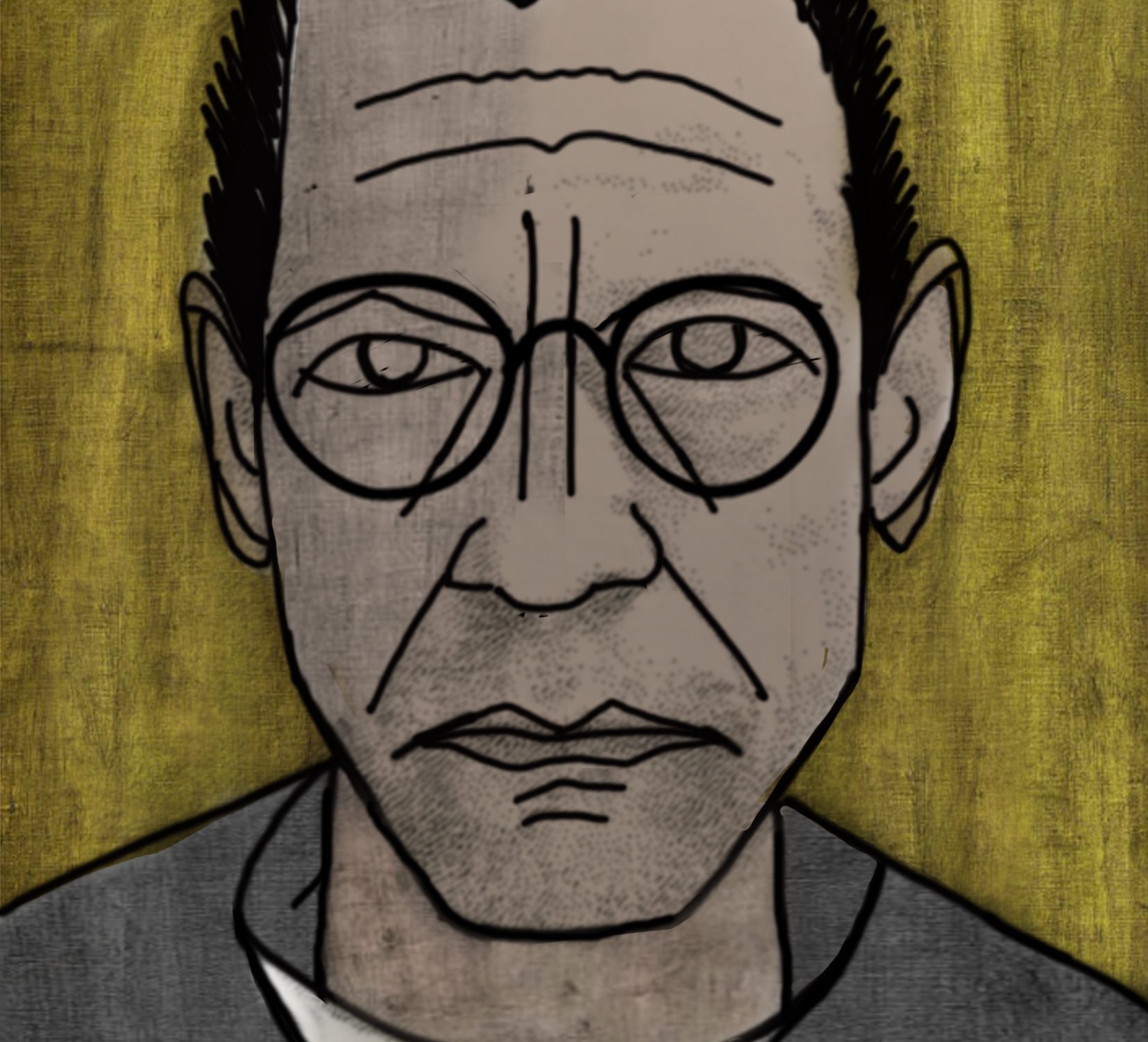

Karsten Greve at FIAC. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

There is no mention of Bernard Buffet on Musee d’Art Moderne’s Instagram page as if they are afraid of being seen as more no-brow than lowbrow, but I liked it very much. Especially after reading the biography Bernard Buffet: The Invention of the Modern Mega-artist by Nicholas Foulkes, which spun the tale of a destitute artist working in poverty before rapidly achieving fame and fortune (that rivaled Picasso in 1960s Paris) at a pace only exceeded by the backlash against him. His undoing could be tied to the hubris of being depicted in a society mag suited and booted beside his uniformed chauffeur and shiny new Rolls Royce—Buffet never drove, in front of the gated drive of his grand chalet. Kind of like Mark Grotjahn if you’ve ever paid a visit to his Instagram account.

I’m not proposing Buffet’s is a particularly great body of work or due for reconsideration or reassessment, just that sometimes we need to be reminded to look; I find that I get inured to the art world’s steady diet of obvious things by obvious people. Buffet paints himself bigger than life, with spidery, elongated features, gaping mouth and horse teeth with an unforgiving, deprecating eye rendered in grim colors. I was left with scratchy marks on the brain: French hardcore that, best of all, you won’t see at any art fair!

Carl Andre’s elegant blocks brought to mind another Sehgal work entailing slow-moving actors across an expanse five times the space of a football pitch at the museum next door, an unexpected connection, like tombstones in a cemetery, a pre-FIAC palate cleanser.

The Running of the Wealthy Bull-headed Bulls

I got another call from a fair insider this time from the folks at Frieze listing galleries that blew off FIAC but are still Frieze-ing as of 2016, the only time I get to use a ballpoint pen is when I get sneaky/sniping information my informants refuse to commit to texts or emails. These galleries included Hauser & Wirth, Matthew Marks (damn him for not selling me the Price drawing), Tanya Bonakdar, Greene Naftali, Andrew Kreps, Tina Kim, and Franco Noero. The mole also mentioned not to forget Zika, looming over Miami like a specter from another kind of horror film. How could you not be amused?

In fairness, Frieze may have done better than I previously reported (for some at least) and it was my mistake not to acknowledge the ebbs and flows from fair to fair, year to year; overall, I’d rather suggest the results boil down to a pretty standardized bell curve. One gallery told how they sold their FIAC material from their Frieze booth. Go figure. The overriding complaint from participants was the local character of this year’s FIAC, especially the paucity of Americans, making for a sleepier event. Phones serve a similar function at fairs to the white canes used by the blind: people tend to see with them.

I never attend fairs at the onset of the initial openings in fear of a stampede of wealthy bullheaded bulls even when I have an early access pass, but in truth, FIAC is the only fair (and trust me, there are too many to tell) that doesn’t send me an early invite, or for that matter a late one. Hmm.

Sadie Coles, always a consistent seller no matter the port of call, was in fine form; not least because her booth, a solo outing by Urs Fischer, was nearly sold out hours into the fair—typical for her. Fischer, an artist of his time who produces with the velocity of a virus is always at the ready to fill booth, gallery or museum (he’s regularly got all three on the go at once).

One of Urs’s works was a realistic, rock-like chair and footstool formation that happened to be made from foam in an edition of 12 with the requisite number of artist’s proofs that aren’t really anything more than more of the same. And the refrain that each one in the edition is unique is but another foray into the land of selling what used to be called multiples. When I asked Sadie if it was archival she replied: “No, it’s $25,000 of fun.” She wasn’t finished, stating the piece reminded her of me. “You mean childlike and exuberant?” I asked. To which she fired back—without missing a beat: “No, cheap!”

David Zwirner unsurprisingly had the requisite $400,000 Yayoi Kusama, $1.6 million Sigmar Polke, and $750,000 Franz West (all unsold as of the time of my visit), significantly more expensive than West’s works at Larry Gagosian and Per Skarstedt, where large scaled aluminum pieces were priced at $375,000 each, respectively. Larry G. sold his orange seating object swiftly (and just about everything else hanging) but Per didn’t have such luck with his phallic shaped, poo brown scatological sculpture. The Gagosian-ista I chatted to had removed his badge so as not to have to field questions by fair-goers, a man after my heart.

Carl Andre at the Musee d’art Moderne. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Stalwart Karsten Greve, who I adore and respect as much as his prices are high, expressed his general grievances by erecting a chain across half of his booth, restricting ingress in a nihilist act of defiance I can only laud and breathlessly admire. Paula Cooper sold her gold (Rudolf Stingel) for $1.5 million before the crate was unpacked and Christophe Van de Weghe’s Stingel (a recent resale) was on hold for around $2 million. The Cy Twombly I previously reported as being sold from Van de Weghe’s Frieze stand to Mnuchin Gallery made a surprise reappearance, back on the market. In the art world, no deal is consummated until the funds clear.

303 Gallery sold out of its expressionist paintings on mirrors by Nick Mauss, Canada sold out a sensational, vividly colorful and stupid group of Katherine Bernhardt paintings (up to $60,000) of the Pink Panther—I was smitten; and Simon Lee sold a potpourri of art from Jeff Elrod ($150,000) to Michelangelo Pistoletto and Sarah Crowner.

The main alternative fair that replaced the lousy FIAC sponsored iteration is Paris Internationale housed in a lavish, dilapidated uninhabited mansion. But there’s so much art in so many bathrooms it washed the whole thing out except for standout paintings including the staunchly non flip-able frontal nude bits of Celia Hempton at Sultana in Paris, juvenile race related canvases by David Leggett at Chicago’s Shane Campbell and the hackneyed though huggable cartoon creatures of Edward Kay at Rob Tufnell of London. They were all available for under $10,000 the way things ought to be in the emerging market.

It’s Always Better Here

I am an admitted art market navel-gazer. I have received much feedback over the years from my columns including the fact they are frequently too long, that I’m a guilty pleasure, a mean gossip, and a famous anarchist; though, with a wife and four kids dealing high end art and classic cars, I’m hardly a Molotov wielding rabble rouser. Honestly, it saddens me. I know I am all or most of those things but on another level I’d like to be seen as honest, informative and entertaining, a chronicler from the transaction trenches telling a story few if any cover.

After nearly 30 years on the job, when you’ve been in business as long as I have, they like you even when they hate you. It wasn’t images of the fair that stuck in my craw or the artless provocations by Tino Sehgal, but something altogether different—rather than the slogan I’m here for the beer, I’d say it starts (and ends) with the art. A booth minding friend summed it up best by the comment, “I’m from the Mid-West. It’s always better here than where I’m from.” No matter where here is, when it’s a here infused with art, I’d have to concur.