This story first appeared in the January 2017 issue of British GQ.

The world has changed in the last five months since I wrote this. Much of Jerry Saltz’s medieval (over sexualized) mischievousness has been replaced by multi-colored, grade-school crafty signs made for the internet inciting sedition against the as-yet-formed Trump administration. Saltz has become the social media Thomas Paine of pamphleteering and his art career may yet finally loom: photos, proclamations and porn.

SEX AND ART ARE THE SAME THING–Picasso

From failed artist to Facebook fetishist, Jerry Saltz is a critic like no other. The one-time trucker turned Pulitzer-nominated writer has used his online persona to rail against the wild excess of the market and claim his place as art’s social-media poster boy.

A bat’s private parts, ancient Greek naked girls and boys, enemas being administered, sex from every entry point imaginable, tits, penises, balls, vaginas and asses in every shape and form. Let’s not forget gorilla sex, too. And this is just a one month recap of Jerry Saltz’s, shall we say, colorful Instagram output. You might not immediately get it, but all this derives from the world’s most famous and celebrated contemporary art critic. Oh, and I’d be remiss for forgetting all the peeing and defecating by the young and old, human and animal, on any and all comers.

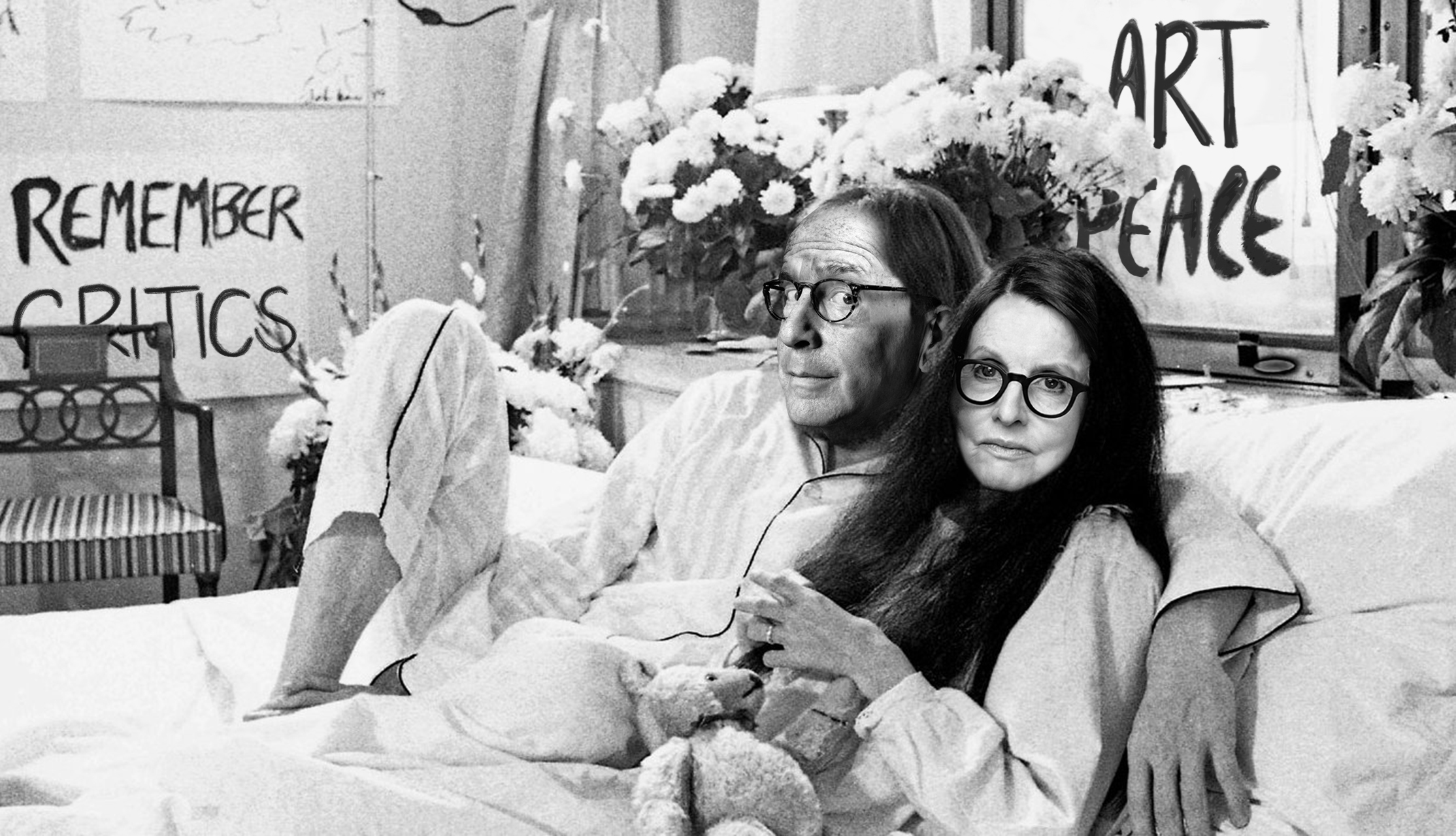

I have known American critics Jerry Saltz and his wife, Roberta Smith (of the New York Times), for nearly 30 years and read just about every word either has ever written. As a curator, all I ever wanted was to be reviewed by Saltz and Smith (she complied more than he). You imagine them working side by side, furthering the art cause like John and Yoko protesting for peace in a bed-in.

Married in 1992, Smith is a brilliant, stern, latter-day schoolmarm and Saltz a boundary-pushing populist who changed the game of how critics communicate and cultivate audiences (his is probably the largest since the form’s ancient advent).

Saltz’s launch is well-trodden territory, but in a nutshell, he’s from Chicago, failed as an artist and gallery owner, then drove long-haul trucks before—as a self avowed late bloomer—he began writing about art in his forties for Art in America, Frieze, Arts Magazine, Time Out New York and the Village Voice (where Smith cut her teeth) before assuming his present role at New York magazine.

What’s less known is that Saltz’s father operated a lingerie company after emigrating from Estonia and his mother committed suicide by jumping out of a window when he was only 10. With no female presence whatsoever—he’s got two brothers and two stepbrothers—there were no sisters, aunts or even grandmothers to mollycoddle him, which surely colored the outlook of the man we know today: a walking, talking figurehead for all that’s good, bad and ugly about art, artists and the art world. And which may go some way to explain his ubiquitous pornographic provocations and obsessions (more on that to follow).

Saltz’s writing voice is colorful, conversational, lively and erudite, a feat none too easy to repeat. He is the recipient of three Pulitzer Prize For Criticism nominations, but more than that, Saltz and Smith are the defenders and evangelists of galleries, and those who man (and woman) them, as much as the artists who fill them. Like midwives, they walk us through a contemporaneously unfolding slice of art history in real time, explicating all from the trenches of their beat: namely, international art as seen and experienced (primarily) in New York and its environs.

Collage by Kenny Schachter. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

A star is born

One morning back in June of 2010, Saltz woke up like the character in Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, but instead of a cockroach he had mutated into an unsuspecting reality TV star. Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, an epic overstatement if ever there was one, produced by actress Sarah Jessica Parker, was intended to discover and crown the next Jeff Koons.

On each of its two series, 14 artists competed for $100,000 and a one-person show at the Brooklyn Museum—so much for institutional integrity. China Chow, more esteemed for being a model and the daughter of restaurateur Michael Chow than as an art aficionado, served as host and another judge (besides Saltz and others). I wonder how Chow’s father, a recent convert to painting, would have fared on the show.

The program unleashed within Saltz the latent persona that he always knew existed: a newfangled art media spokesperson, small in stature but larger than life. Before his starring turn, Saltz visited one of my curatorial efforts in the mid Nineties. He was chief critic for Village Voice and I remember him dropping that favorite C-list line to some unsuspecting (and attractive) artists: “Don’t you know who I am?” But Saltz rebooted was and is an ebullient, impish cutie that continues to grate on many, yet endears him to more.

Like Nick Broomfield, the documentarian who inescapably inserts himself into the narrative of the lives of the subjects he reports on, Saltz took it a step further by reviewing himself, the show and behind-the-scenes production. It was all too masturbatory, as the program sucked from the get-go, even before it died a premature death. The only real artwork that emerged from the initiative was Saltz himself, the self-created, self-centered masterpiece he could never make in his art studio.

Social media re-reinvention

There was a perfect storm: Saltz’s TV notoriety coincided with the advent of social media and the explosion of the art market onto a global stage stoked by the boogeymen of big bucks, glamour and lack of attractive alternatives in the financial markets.

Jerry hitched his fate to Facebook back in 2011, where he proceeded to spearhead a novel form of democratic art communication by ushering in an era of participatory criticism; in the process, he opened the floodgates. Art, politics, race, religion, gender and sex, all were ripe for discussion, depiction, dissection and/or denigration. It culminated in a short-lived New York magazine column in which Saltz became the art world’s agony aunt.

For better or worse, Saltz exposed himself in a way few had experienced since 1972, when Vito Acconci masturbated in Sonnabend Gallery, New York, as a piece of performance art. But even Acconci was obscured, hidden away under false flooring; Saltz lets it all hang out about three times daily.

Facebook, where all the crazies come out of the woodwork, is about social intercourse in a fashion from which Instagram recoils (despite sharing the same owner); threads of arguments can rage for years. I miss it dearly since I got expelled for posting an image Acconci’s hairy ass from an exhibit at the Museum Of Modern Art. OK, not the most appetizing of things but not exactly reprobate.

Back in 2013, an internet eternity ago, I wrote that Saltz’s Facebook audience of more than 35,000 (this was before he signed up to Instagram in 2014) was analogous to filling an Olympic stadium for criticism, a form of writing that is regularly declared dead. As of writing, Saltz boasts 190,000 Instagram followers–a status few denizens in the art world could match and dwarfing his Facebook following (about 83,000, including subscribers, not to mention more than 78,000 on Twitter, which I never took up as I can’t think in 140 characters).

Saltz’s unrelenting social media fetishes don’t titillate, rather they annoy—but then again he’s still on, I’m off—and include pictures of ancient sex, animal sex and anal sex; he’s an equal-opportunity, nondiscriminatory pervert.

Instagram is more tolerant, and at the same time less a platform to proselytize, grandstand, and seek revenge (hence my Facebook banishment), perhaps because it’s more commercialized and nothing sells more than sex, not even art (unless replete with nudity).

Saltz vs the art market

Art is philosophy in pictures with price tags affixed. If indeed Jerry Saltz has no beef with art fairs, auctions and the market—he “loves it” he assured me in an email—you wouldn’t know from reading him; he’s spilled tons of ink, and ones and zeros online, complaining. But art and money have been bedfellows since art came off the walls of caves, and it’s not going to stop anytime soon, if ever.

In his countless writings, Saltz has railed against great collections being broken up, sold off as lots to the highest bidders and unlikely to see the light of day again. He has beseeched auction houses and sellers to exhibit a conscience by helping museums raise money and offering significant price breaks. All well, good and admirable, but we live in societies where individuals have the choice to decide for themselves what to do with their time and money.

More socialistically, Saltz has called for price caps on artworks, starting at $1,500, far from the starter figure of $25,000 that a young artist may fetch today. He remarked that a zero could comfortably be lopped off every invoice amount, from emerging to established artists, in essence devaluing art. Sounds to me more worrisome than a market run amok.

Saltz is none too pleased with the mega money fat cats he deems not worthy of Hirst’s diamond skull, but he misses the fact that the trickle-down economic spillover supports us all. Saltz believes that referring to himself as always starving (and on occasion posting bank receipts that reflect his micro-balance) gives him license to take the piss out of the ecosystem that produces $300 million works of art and those that countenance, even embrace it.

I am of both minds regarding monster painting prices and can see how the spectacle incites anger and always will. But art in museums, and there is plenty still, is accessible and without entry fee in many venues. And they say there is no such thing as a free lunch.

In his own words from a 2012 New York column, Saltz laments, “In the last decade, art fairs mushroomed and became all-encompassing, fully comped VIP monstrosities and entertainment complexes for the one per cent.” On the topic of the recent fad for curated auction sales Saltz jibed, “I say it’s all just a bullshit ploy to massage client egos and reel in rubes.” I’d say it’s just another way of trying to refresh the constantly repeating chore of having to sell more.

Saltz grates at the supposition collectors could enter art history by flashing astronomical sums; witness the surfeit of private museums in the last 25 years, a phenomenon that’s currently booming in Asia. Says Saltz on the topic, “High prices become part of its temporary content, often disrupting and distorting art’s nonlinear, alchemical strangeness. Art is long. The market is not.” I’d rephrase it: art is long and so is the market. Sometimes they profoundly reflect one another, other times not. And so it goes.

Yes, you can lament the market for the sake of its capricious frailties and at times incomprehensible nature. Yet it’s as much a part of human nature to trade as to create. And so what? You can’t begrudge the market for being… a market. As a cynical idealist, I shall always hold out the hope of an aesthetic meritocracy that defeats all disingenuousness in the field.

What future for the famous critic?

Jerry Saltz is the anti-critic critic, making critic-art out of the whole cloth of himself. Saltz is human Prozac; always “on,” he’s forever cheerful, an antidote to life’s chores and routines, maybe shying from his family history of despondency. I can’t remember ever seeing him grumpy or imagine him out of character, even in the midst of pillow talk with Smith.

But don’t let the cloak fool you. Underneath Saltz’s puppy dog persona he does not suffer fools lightly and is known to ruthlessly strike out at those he disagrees with (almost always men), unfriending and offering a cold-shouldered future.

Saltz deservedly basks in the limelight, fame and acclaim that transmogrified him. He is a supernova schmoozer and elfin grass-roots rabble-rouser. He is the most popular (ever) populist, in the vein of Matthew Collings or, better yet, Sister Wendy, but with a much wider audience than both—and all others—combined.

I can envision Saltz on Speakers’ Corner on a sunny Sunday, reeling in the crowds with the hilarity of his humor and self-deprecating nature. The Saltz shtick is an act worthy of the Borscht Belt (the now-defunct so-called Jewish Alps in upstate New York), which he could in all seriousness successfully take on the road more than he already does on the lecture/teaching circuit.

Saltz is a sex-crazed, workaholic, prolific old war horse who chides writers that don’t write every day. He regularly posts images of the enormous coffees that fuel his words, which haven’t stopped flowing since I first put my head inside an art gallery. And although he never reviewed a single show I curated in 25 years, he’s invariably complimentary on Facebook and in correspondences. I cherish any missives from Saltz and Smith and consider myself lucky to have the dialogue I’ve had with both over the decades. Thanks, guys.