Prince v. Trump

Without getting too much into the minutiae of Immanuel Kant’s concept of the “thing-in-itself,” as posited in his “Critique of Pure Reason” (1781), in which he wrestles with the differences between noumena and phenomena, I will say that there is no disputing that Richard Prince (b. 1949) made an Instagram portrait of Ivanka Trump, at her behest, in 2014, and sold it to the First Daughter Elect netting $36,000. Though he claims to not, generally, undertake commissions for hire.

On January 11, 2017, Prince Tweeted: “This is not my work (Ivanka’s painting). I did not make it. I deny. I denounce. This fake art.” And on Friday the 13th, which was more like April Fools’ Day, he wrote on his site beneath the heading Birdtalk (Prince claims he invented Twitter, but we’ll leave that for another occasion): “I’m not after attention or publicity… I made the art. And I can unmake the art.” He proceeded to return the proceeds of the transaction via an unnamed art advisor (there’s no escaping them).

The issuance of an invoice and subsequent payment signifies an offer and the offer’s acceptance, constituting evidence of a binding agreement. Both parties received benefits, or consideration justifying the arrangement; the terms specific enough to warrant enforcement—money for art, art for money. Despite easy jokes, I don’t think the competence of either party could justifiably be contested. Thus, the criteria for a binding deal was unequivocally satisfied (I did pass my bar exam some 30 years ago).

The repercussions to the market if artists had the right to impugn the authenticity of their works after the fact would turn the art economy topsy-turvy, destabilizing what many already judge to be a thinly traded, tenuous ecosystem to begin with. The whole enterprise cannot be pegged to the capriciousness of artists, fickle at best: the laissez-faire markets with their (quasi) built-in checks and balances would lose confidence in art. And Richard would be robbed of his private-plane-fueled, St. Barts lifestyle; that, I am sure, he can appreciate. And besides, you don’t kill the (market) animal to remove a splinter from its foot.

Screengrab of Richard Prince’s Twitter feed. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Of course, Jerry Saltz had to weigh in, stating in his New York Magazine column that Richard Prince’s provocation was a veritable new genre of conceptual protest art (beyond Prince’s early 1990s Protest paintings). I love Jerry and appreciate his giddiness with this deed of civil disobedience, but he doesn’t know from the market or having to subsist on buying and selling art. It’s an arcane language he doesn’t speak.

Recounting Ivanka’s art stash, Saltz related that she owned a Wade Guyton, which was followed by a disclaimer: “This article has been corrected to show that Wade Guyton has not sold a piece to the Kushner-Trump family.” Seems Mr. Guyton apparently lodged a demonstration of his own, which doesn’t mean the “Kushner-Trumps” didn’t acquire a secondary offering off their trusty adviser.

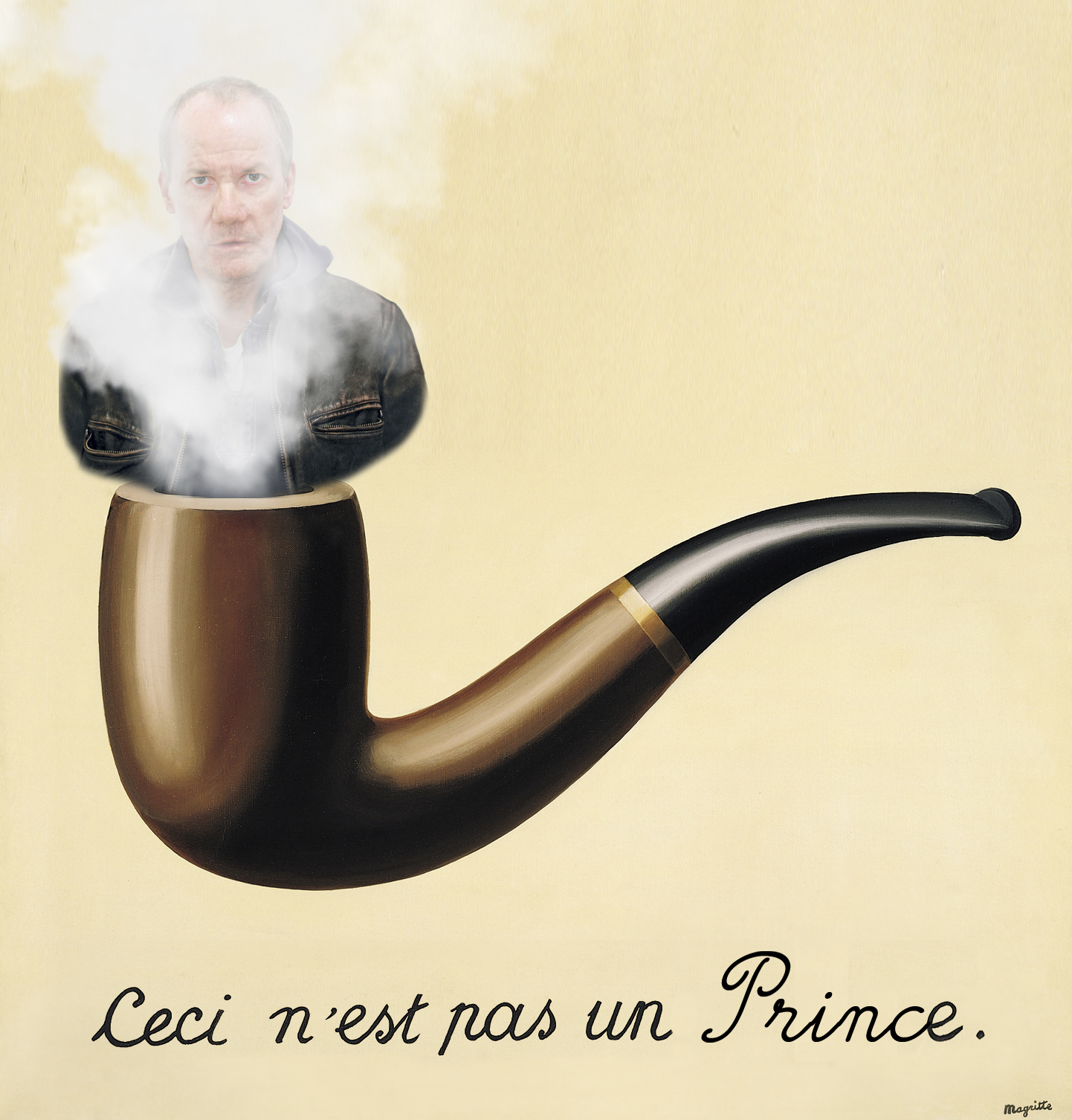

I think Prince’s was a cool, hilarious and (perhaps) historic act of underhanded naughtiness, but it’s ineffectual diddly-squat in the face of market forces. The notion of saying a piece signed and paid for directly from the artist is not art is as absurd as Magritte’s painting of a pipe, “La trahison des images” (The Treachery of Images) from 1928-29, is adroit. The market will suck up anything it deems worthy of a buck, artist intent be damned.

Granted, Richard invented a new post-art art form and I am going to name it: the magic of Art Market Metaphysics. In what other sector can you conceivably disown something that is what it is? In fashion? I doubt that would go over well if a designer didn’t like the way you sported a particular garment. Is it too late to repudiate my kids?

And if Prince didn’t want attention, Tweeting was hardly the recourse—in that he shares a very public platform with his nemesis Donald J. Trump—the gesture was, in my estimation, if not a bid for publicity then a duplicity stunt. It’s like measuring altruism by the number of museum rooms named after a donor lauded for selfless generosity and in the process having his and/or her subjectively accumulated art prominently displayed (cf. SFMOMA collections on view).

Gerhard Richter. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

The Precedence of Disavowal

Malcolm Morley (b. 1931) attended an auction in Paris in the 1970’s for the purpose of defacing his work by writing “fake” on it with a paint-filled water pistol. The auction house had been tipped-off and covered the painting in plastic, but Morley nevertheless nailed the gun directly to the canvas; he halted the sale but the work was eventually sold to a Swedish collection and now resides in the Pompidou collection. Long live nihilism.

Gerhard Richter (b. 1932) has excluded the realistic, figurative paintings he experimented with from 1962 to 1968 from his catalogue raisonné. You imagine he conducted an official ribbon cutting ceremony for his first officially sanctioned canvases. I’d step up to own any one of his self-disputed paintings. Richter has stated he believes his present precious prices are pornographic. Speaking of which, Gore Vidal disavowed the 1979 film Caligula after he claimed his initial script had been rendered too explicit.

Cady Noland (b. 1956) who quit making art decades ago is for all intents and purposes a dead artist as far as her output is concerned, with a record of nearly $10 million. Instead, she has assumed the role of tireless shepherd of the wellbeing of her previously created bodies of work. Most recently, she succeeded in shooting down the validity of a piece that had been reconstituted for conservation purposes after living a hard life outdoors. Many a piece has recently been withdrawn from auction when Noland has questioned something or other. Her time would be better served leaving the art to the art world; if she’d like another challenge, she can try corralling my errant children.

Robert Gober (b. 1954) once denounced a dollhouse sold at Christie’s declaring via wall label that it had been done as a work of carpentry for hire (and the bidet had been removed and wallpaper changed in one of the bathrooms). Though his was a more plausible position for renunciation, the work has repeatedly sold at auction since, the last time in 1998 for $68,500.

Robert Gober Dollhouse. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Ligon v. Schachter

In 1995 I purchased two pieces by Glenn Ligon and Janine Antoni from Jon Tower, an emerging artist that showed in the early 1990s at Randy Alexander Gallery and Colin de Land’s American Fine Art for about $900 each, that had been given to Tower as gifts. Considering the markets of both at the time, it was a significant leap of faith. Ligon, known for blackened out text canvases, based his series of paintings in which he stenciled in oil stick the descriptions from newspaper profiles of the five youths charged with rape, and later exonerated, in the 1989 trial of the Central Park Jogger. In addition to the canvases, Ligon produced a series of realistic, mannerist charcoal drawings of the defendants on paper. Among the art I purchased from Tower were these classical portraits.

The piece by Antoni was a study for an edition of brooches she made from impressions of her nipples, cast in gold. The maquette was painted in a lifelike fashion and rendered in plaster; handmade and unique. Funny enough but less amusing, Antoni, and Ligon before her, both disclaimed the pieces as art. Antoni refused to participate in a group show I curated until I surrendered her nipples in exchange for a (much) lesser editioned piece. I did so begrudgingly.

When I tried to sell the three framed Ligons at auction six years on, in 2001, the artist phoned up Sotheby’s and said these accomplished works on paper were not art and they were withdrawn (although they are incorrectly listed on Artnet as Bought In). In fact, they were as much or more so than anything he (or she) had made in the name of art before. Another six years later, in 2007, Phillips rolled the dice and went ahead with the Ligon sale and, despite the protestations, the works sold reasonably well for $8,750.

Glenn Ligon, drawings. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

I assume the artists found the works inconsistent with the images they wanted to convey in some respect. With a $4 million auction record today, I should have complied with Ligon’s stab at image control and held on. Must art be sold like cigarettes, with warnings? The purchaser of my drawings split the three portraits, (disingenuously) gave them new names, “Portrait of a Man” and sent them all back to auction between 2008-2011 and then again (in the case of one), where they bought in three times while the other re-resold for $4,000. I wonder if Phillips returned them to the artist. If so, he’s lucky to have them.

In 2012, I received the following letter from Phillips:

The studio of the artist Glenn Ligon has recently declared as inauthentic three untitled drawings that you consigned for sale and which were sold in our November 16, 2007 auction of Contemporary Art. Pursuant to Paragraph 8(c) of the consignment agreement that you entered into in connection with the sale of the drawings we are hereby rescinding the sale of these works as a result of the breach of the warranty of authenticity. We would appreciate the prompt repayment to us of the net sale proceeds in the amount of $10,000 paid to you in respect of the sale of the three drawings to you.

As if. I wrote to Phillips at the time that those works were indisputably by the artist and I proffered that I wouldn’t pay a cent back under any circumstances. I may have mentioned I was happy to take the issue before any court and the international press. Their response was swift:

Dear Mr. Schachter,

As a measure of good faith we will handle this matter directly with the purchaser of these works. I sincerely apologize for any alarm or inconvenience this may have caused you. Please disregard my previous email and the mailing which was sent to you yesterday.

We need to keep calm, maintain sanity, and give Trump a chance to hoist himself on his own petard before the widespread calling for his tarring and feathering. It’s getting a bit stupid, (especially) with art people on social-media, threatening the heads of Trump and his family like Lord of the Flies. In the UK, you can place bets as to whether the administration will last for the full term or end early (before4—I should trademark that!). In a sense, Richard Prince is inadvertently making the Trump clan more sympathetic, as if they’re getting pooped upon by the snooty (and filthy rich) cultural elite.

I embrace the Prince that annoys and irks at the ripe age of 67. It’s galvanizing. He’s made an intellectual fissure out of whole cloth, a ghostly ripple like a skimming rock in a multi-billion-dollar pond. Despite unassailable authorship of a work of art, Prince has managed to shift meaning midstream by the power of words alone; art and economics and in this instance, the art of economics, employed to drive home a (political) point. Granted, we are contending with first world problems like $1,200 sweaters intended to fall apart by design.

I suggest sticking some Richard Prince brand weed (you can buy it at Blum & Poe Gallery in LA, surprise!) in your pipe and smoking it while pondering the folly of this episode. Yes, Prince has thrown a wrench into the art market, he’s a great disruptor; but I have news for you, the thing itself, the Art, is divorced from the aim of the artist. Ivanka, please put your pariah piece up for sale and see how right I am; Phillips would chomp at the bit for it and so would I. Trump wants to make America great again—you don’t have to do that with art—it’s always been.