Another year has gone by, and with it another holiday spent in the mecca of money (and art), St. Moritz, where my in-laws, avid skiers all, have been vacationing for decades. Due to the of fear of god—or, rather, catastrophic injury—I hung up my own snowboard years ago, but there’s still plenty to keep busy on the trading floor, er, I mean hotel lobby of the Kulm Hotel (owned by the fabled Niarchos family) and at the glut of galleries in the immediate vicinity, which, for me, pose a risk equal to strapping on skis. Minutes into my first run—to see art—I barely made it five steps before I went flying onto my ass and nearly broke my neck. Who said art isn’t rife with risk? After being pitied by a child and helped to my feet by a charitable eighty-something woman, I dutifully soldiered on, bruised but undaunted.

On the slopes and off, the town is a diverting battleground for the ultra-rich. Lunching with Belgium’s premier gallerist, Xavier Hufkens (who is about to open his third gallery in Brussels), I happened to overhear the conversation at the contiguous table—sorry, eavesdropping is part of my job description—describing Larry G. as a “dishonest prick who inflates prices and has authenticity issues.” Charming. The son-in-law—okay, my snooping may verge on encroachment, so keep that in mind next time you dine next to me—went on to ask if his “collector” friend was going to flip a painting that had recently risen threefold in value. At another meal, a spec-u-lector, said to me with a dismissive flick of the wrist that George Condo is Picasso for the poor (though at $2.5 million on the primary market, I thought it was more like expensive crap for the rich). His French accent was so thick I misheard it as “Condo is Picasso for the pool”—I think I will adopt that version for future reference.

George Condo: Picasso for the pool! Illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Out and about were the Zabludowicz family, Leon Black, Marilyn and Eyal Ofer, Howard and Andree Shore, and even my favorite attorney, Richard Golub—who upon spotting me, angrily grumbled under his breath, “You’re even turning up here?” He’s learning to keep a lid on his violent outbursts, which I have chronicled in my column, though I still might benefit from wearing a ski helmet to tea.

But St. Mortiz isn’t all contact sports—another competitive pursuit is iPhone art bingo, a mix of trying to stump one another in identifying the latest “hot” artists, and then showing off recent acquisitions. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not all big-money shenanigans. Another dealer family at a nearby hotel (there’s a veritable avalanche, feeding off the monied set wherever they congregate), asked to do some laundry at our house. Freud defined parsimoniousness as being associated with an emotionally charged fascination with defecation. Sounds about right.

St. Moritz un-chic Schachter style. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The year 2020 won’t mark the onset of a decade of bad behavior—that’s every year in the (art) world—but rather a time when more trouble will bubble to the surface than ever, with a rise in concomitant accountability. Galerie Gmurzynska, for instance, went absent from Art Basel Miami Beach and is skipping Art Basel Hong Kong while it deals with ongoing court proceedings (and a fine in the millions) for assisting collector Urs Schwarzenbach in the avoidance of VAT on nearly 100 works of art, many of which made it into his Dolder Grand Hotel in Zürich—which, by the way, recently began accepting Bitcoin as payment.

Gmurzynska denies that they skipped Miami because of the lawsuit, claiming that they decided it wasn’t relevant to the presentation of Modern art; it remains to be seen if they will reappear in Basel-Basel in June. Funnily enough, the Art Basel Art Market Principles (the fair’s code of ethics) were written with the assistance of the gallery’s part-owner, Matthias Rastorfer. Art Basel had no comment. Meanwhile, I hear another major multi-venue Swiss gallery is also under investigation. Dissimulation is the concealment of one’s thoughts, feelings, or character—or, in case, of art dealers/spec-u-lectors, all three. Art hypocrites, or “hippocritters,” as I refer to them, are the non-endangered art-world version of hippopotamuses.

Gabriel Schachter ponders what’s in store in the New Year. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I will never forget the episode of the classic TV comedy “The Little Rascals” when they were building a go-cart—not simply because I like cars, but as an instance of the circuitousness of life (in the art market). Every time one rascal finishes screwing a wheel onto the axel and then proceeds to the next, his assistant, unbeknownst to him, removes the wheel he had just affixed and hands it over to be attached anew, making for a never-ending loop of futility. This, is in a roundabout way, brings me to the Daros Collection and its continuing deaccessioning. Established in 1997 after the untimely death of Alexander Schmidheiny, partner of legendary dealer Thomas Ammann, and then passed onto his brother Stephen, the collection has since been pruned from about 1,000 works by the likes of Warhol, Twombly, Richter, and Ryman—among other masters from the second half of the 20th century—to less than 300.

The Daros Collection recently unloaded a painting from Twombly’s famed 1961 “Ferragosto” series to Steve Cohen for $85 million—and it’s now said to be on the market again for $95 million. (Meanwhile, a famous Greek collector sold another Twombly to the Mexican financier-collector David Martinez for upwards of $150 million.) Cohen’s advisor, Sandy Heller, is about to open an office in Paris, by the way, helmed by Jean-Olivier Després, who was poached from running Gagosian’s Paris outpost. Why do these players persist in this game that resembles the Little Rascals’ go-cart assembly line, buying a peerless masterpiece in order to sell it… in order to buy another peerless masterpiece?

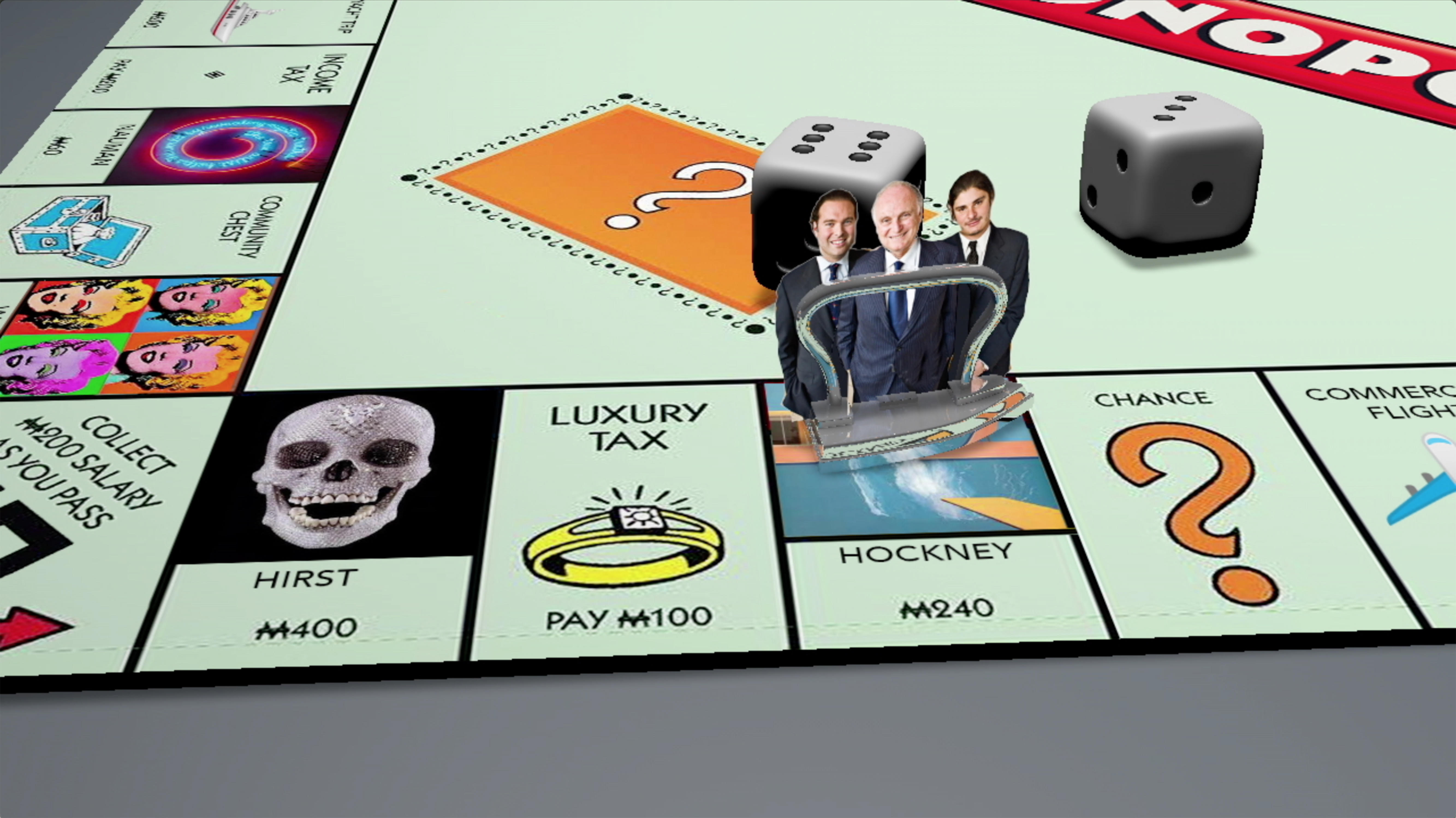

Because they can. Because they have commitment issues. Because trading is in their blood. Or maybe it’s closer to the board game Monopoly, where instead of simply buying all the great properties you can on the way to victory, a buy/sell component is added for extra kicks. This rabid art-world wheeling-dealing impulse comes at the expense of donations to museums, where some of these masterpieces belong. Even lowly I am doing my civic duty here, giving a handful of my less-than-masterworks—along with my archives—to Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies.

Another Swiss gallerist I know with a deep inventory—for this reason alone I love dealers more than anyone else in the art world (besides old-school critic Roberta Smith) for their no-holds-barred art obsessions—was asked if he wanted a mega-loan to “acquire a plane, a boat, or house?” to which he unequivocally said no. What about to buy more art then, he was queried. Again, the response was a flat no. He was happy with what he had without being beholden to anyone.

But countless others are jumping at the chance for easy art money, which will undoubtedly contribute to their downfall—and I’m not just talking about Inigo Philbrick’s collapse, which might end up being the biggest swindle involving contemporary art ever. (More on that to come soon.) By the way, he’s still in Australia, contrary to last week’s Wet Paint column, where his girlfriend Victoria Baker Harber just made a Christmas present of herself by coming to join him on the lam. Also by the way, isn’t it an interesting coincidence that the only really humorous Instagram art-meme account, @whatanartshole, went silent the week Inigo dropped off the grid?

Hauser & Wirth Hospitality conquers the world and also Sills in the Engadin, near to the Hauser gallery in St. Moritz. Photo illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Lest I forget St. Moritz’s local galleries—where art was on offer at a slight discount this year, since Swiss authorities may be the only regime in the world to actually make buying art less costly, by recently lowering the VAT from 8 percent to 7.7 percent—Karsten Greve had a tremendous show of 79-year-old Joel Shapiro’s goofy Giacometti-like off-balance figures, with prices starting at €150,000. (The artists’s auction record is $701,000.) Elsewhere, Andrea Caratsch had new paintings by Jiri Georg Dokoupil (he always seems to) in the same price range, and Hauser & Wirth—soon to be opening yet another hotel branch in the nearby town of Sills—had overpriced Calder sculptures priced from over $1 million (for a teeny version) to $10 million. (The hospitality business doesn’t come cheap.) Also, New York artist Ena Swansea had new landscape paintings at Robilant + Voena for $75,000 apiece, which, with the addition of a canoe or two (and as many zeroes to the price tag), would be indistinguishable from Peter Doigs.

Papa Smurf meets the Wizened Wizard, aka Francesco Clemente. Photo illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Vito Schnabel, for his part, hosted a Francisco Clemente show—right on the heels of another one in New York a few weeks ago—with works priced from $110,000 to $160,000, and a handful were sold by the opening. Upstairs were vague depictions of clouds (though it was hard to tell) and, downstairs, the artist’s more signature figurations. When Vito was the tender age of 16 I advised him on his first New York pop-up, and he’s come a long way—though his muted aggression towards me was an unusual selling tactic (redolent of the Gavin Brown/Adam Lindemann variety). As for Clemente himself, he was never without a hat that made him resemble a cross between Papa Smurf and a wizened wizard. Hans Ulrich Obrist transported into St. Moritz for a few hours, like a “Star Trek” character, before beaming off to openings elsewhere as only he is wont to do. Kiefer was around, too, for a showing with Thaddaeus Ropac at a temporary space, while Alex Katz had work at Monica de Cardenas’s nearby gallery.

This was my first sober New Year’s since I was… a baby? Eleven months into my own resolution, I’m glad to say that nothing has changed aside from my blood-alcohol level—not my role, and not my view of the art world, good or ill. What has changed, however, is that the wealth in the market has been spread more widely than ever with the continued meteoric rise of artists of color—which led one observer to remark that white artists no longer have “a monopoly on mediocre art” (which is actually a good thing). But disparity is still rampant. After a prolonged period of an overall up market, uncertainty persists—and, like war (Trump may be on the verge of discovering), it’s easier to get into than out of. Don’t worry: like a bastardized Robin Hood, I will continue to steal information from the rich and give to the aspiring rich (and others, too). Maurizio Cattelan called me an “art detective,” which is fine with me; there is so much more to find out.

Despite a 2019 that for personal reasons—the loss of my beloved son Kai—was the worst I have ever experienced, my feelings about art remain undiminished, and I will work harder to be a better father and share more of what I have learned in 30 years in art to any all who will listen and read me. Xavier mentioned that he felt there was often no poetry left in the art world—but, for me, it’s all poetic, even the tragic, painful parts (of which there are too many). Next up, I have a keynote talk in Barcelona for the “Talking Galleries” symposium on January 20th [Ed.’s note: Artnet News’s Andrew Goldstein and Tim Schneider will also be presenting, so be sure to tune in.], a curated show of works by Roger Hilton this month at Nino Mier Gallery in Los Angeles, another Sotheby’s online sale from my collection (entitled “Bingeing”), another talk at the Zona Maco art fair in Mexico, and participation at the Felix Art Fair in LA, both in February. Then there’s lots more to come in the spring. Sorry everyone! But I can’t/won’t stop anytime soon in spite of myself.

“Only Paint,” my curatorial presentation for Los Angeles’s Felix Art Fair in February, will feature the works of Eva Beresin. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.