Art ecologies, like coral reefs, are fragile things that are highly susceptible to changes: Overheated environments and the trade’s toxic financial ethos can wreak havoc on flora like museum missions and institutional budgets. But unlike the Caribbean’s depleted coral cover, New York’s museum ecosystem may yet bounce back from years of market contamination.

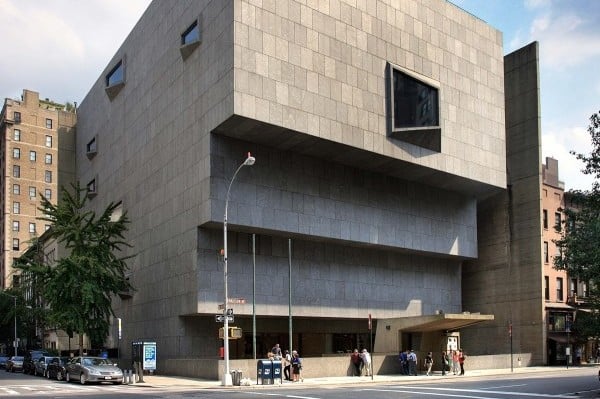

One upcoming development that may prove immensely salutary to New York’s museum ecosystem is the launch of the Met Breuer, which officially opens to the public on March 18. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s much-awaited plunge into the muddy waters of modern and contemporary art has raised expectations, however lukewarm, among specialists and lay folks alike. For a local arts scene that chronically expects institutions to overpromise and underdeliver (with apologies to last year’s launch of the downtown Whitney Museum) the mild anticipation surrounding the Met Breuer’s launch is akin to Star Wars nerds crushing on The Force Awakens.

Thomas P. Campbell.

Photo: ©Patrick McMullan / PatrickMcMullan.com.

When the Met’s Director Thomas Campbell told a gathering of art journalists in early February that the museum “is uniquely poised to tell the story of contemporary art like no other museum in the world” because it can “relay that narrative in the context of 5,000 years of history,” the room did not exactly jump to its feet.

There were, though, faint flutters of excitement in the air. One veteran journalist buttered up a new Met curator by asking: “How will you cope with the celebrity?” Another more serious scribe noted the “petulant” treatment received by Sheena Wagstaff, the museum’s head of Modern and Contemporary, in a November profile in the New York Times.

Sheena Wagstaff

Photo: ©Patrick McMullan / PatrickMcMullan.com.

But these instances of same old new behavior, where blandishments are proffered and professional spats spotlighted, obscure the genuine change the Met proposes to create in the local museum environment. Rather than museum business as usual, the Met’s new branch—it’s first since the opening of the Cloisters in 1938—is considering an epochal experiment. Per the institution’s own recent messaging, the Met’s commitment to an historically and geographically expanded view of modern and contemporary art means the museum can contemplate doing the one thing New York museums have ignored for decades—namely, reconsider today’s market-driven contemporary canon.

Interiors of the Modern and Contemporary Galleries at the Met.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As art historian Hal Foster noted in a recent New Yorker piece on the Met, the museum’s plan to juxtapose old and new art is “exactly what New York needs at this moment, when there’s such a stress on presentness and the fascination with ‘now.’” To this end, the Met’s Thomas P. Campbell embarked on a multimillion-dollar push to modernize the museum immediately after being appointed director in 2009. Among his bolder decisions, Campbell selected architect David Chipperfield to rebuild the museum’s not-so-contemporary Lila Acheson Wing—one critic compared it to an Ohio airport—and effectively relocated the museum’s Modern and Contemporary Art department to the Whitney’s recently vacated Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue (The Met is leasing the famed ziggurat from the Whitney for eight years, with an option to renew).

Additionally, Campbell beefed up the Met’s legendarily fogeyish curatorial team, while significantly expanding the staff’s historical and geographical briefs. Most prominently, Campbell hired Wagstaff away from the Tate Modern—the one institution to have successfully rewritten the global art canon this century—along with seven new modern and contemporary curators in areas of expertise that include Latin America, the Middle East, North Africa and Turkey, and South Asia. Despite having previously turned its back on the art of its time, the Met’s current expansion speaks with a decidedly 21st century voice. Modern and contemporary will be the institution’s principal area of growth for years to come.

But how exactly will this affect programming at the Met and the Met Breuer? That, of course, is the $600 million question (that’s the approximate cost of the museum’s new modern wing, at least). When reached for comment mid-transit between Madison Avenue and the museum’s mother ship, an out of breath Wagstaff told artnet News that “a core strand of exhibitions at the Breuer will look to use contemporary objects to look back at old art and old art to look forward,” with the ultimate goal of “examining issues that have vexed artists over time.”

When asked what this mean specifically in terms of programming, Wagstaff invoked the museum’s collaborations with living artists going back to James Nares’s 2013 exhibition Street. A display that involved objects the painter selected from the Met’s holdings—these ranged from a 3000 B.C. statuette to Garry Winogrand photographs—and his own high definition video, the exhibition intended to “provide a true lesson in close looking across geographic and temporal boundaries.”

Interiors of the Modern and Contemporary Galleries at the Met.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Striking that sort of geographic and temporal balance, Wagstaff insists, will be the museum’s mission where contemporary is involved—an effort to become fully manifest in the Met Breuer’s inaugural raft of exhibitions. These include “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible” (March 18 through September 4) and the first US show of the late Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi (March 18 through June 5). “Unfinished” spans objects from the Renaissance to the present and includes works by Titian, Diego Velázquez, Cady Noland and Robert Gober.

The Mohamedi—though it originates at Madrid’s Reina Sofia Museum—presents the work of an artist unknown by the vast majority of auction house junkies weaned on a strict diet of blue-chip fodder.

Interiors of the Modern and Contemporary Galleries at the Met.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Looked at opportunistically, the encyclopedic institution’s weakness could prove its strength. Consider, for instance, the recent challenge issued by Real Clear Arts’s Judith H. Dobrzynski. This month, the blogger compared a “list of the top best-selling living artists last year” with the Met’s online collection database. Analyzed one to one, her results demonstrate that the museum has clear gaps, which it is not likely to fill solely through spending, due to the multimillion-dollar price tags of leading contemporary artists. But the idea that the Met is obligated to spend heavily—up to $2.5 million for a Maurizio Cattelan sculpture, for instance—ignores the museum’s ability to pull in important donations and also smacks of auction house provincialism. Here’s an alternate takeaway: the Met may be able to afford a hole or two in its collection where artists like Jeff Koons, Rudolf Stingel or Christopher Wool are concerned—while establishing important curatorial precedents.

As with other environments, enhanced competition is itself beneficial for New York’s current museum ecology. In the same way that leading scientists have praised biodiversity as essential for complex ecosystems, the future of New York’s arts institutions depends on a steady stream of new ideas. That, in any event, is the advanced verdict of former Yale Art School Dean Robert Storr.

“Competition is as good for the arts as it is for other things, but only insofar as it prompts genuine change, innovation, and variety,” Storr says. “Now the Met, MoMA, and the Whitney have the rare opportunity to play to their individual strengths as approximate equals.” In environmentalist lingo, the message is not think globally, act locally. It’s plant but with a purpose.