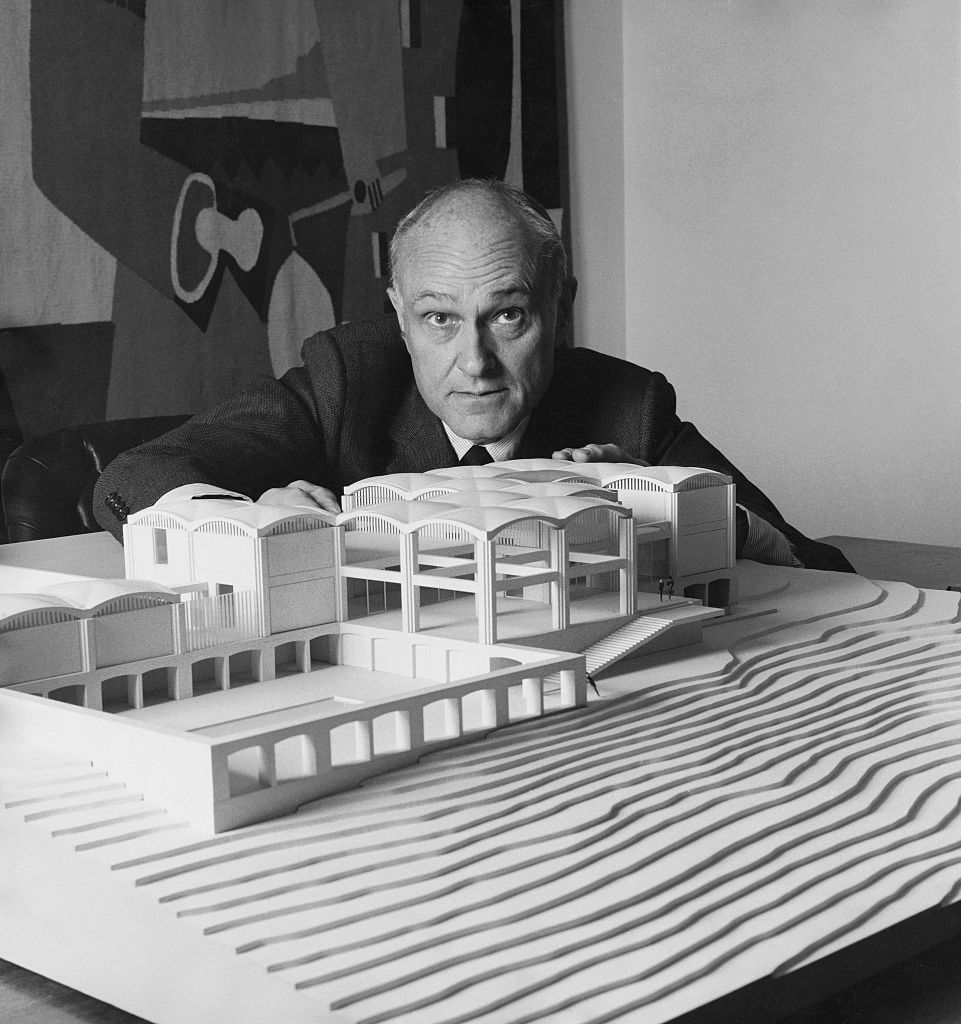

A collective of artists and designers will obscure architect Philip Johnson’s name from a gallery dedicated to him at the Museum of Modern Art during the run of the museum’s current exhibition about architecture and the communities of the African diaspora, “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.”

Johnson, the famed Modernist architect with well-documented fascist and white supremacist views, will have his name covered by a 10-by-10 foot denim textile conceived by the Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC), a nonprofit group formed by 10 architects and designers in the show.

Printed on the artwork is BRC’s “Manifesting Statement,” which argues for the importance of architecture in reconstructing a “nation constituted in conflict.”

“The Black Reconstruction Collective commits itself to continuing this work of reconstruction in Black America and these United States,” the statement reads. “We take up the question of what architecture can be—not a tool for imperialism and subjugation, not a means for aggrandizing the self, but a vehicle for liberation and joy.”

The move, first reported by Hyperallergic, comes after numerous public calls for the museum to disassociate itself with Johnson.

Last December, an anonymous collective of architects called the Johnson Study Group issued an open letter calling on MoMA and the Harvard Graduate School of Design to remove his name from all titles and buildings at the institutions.

Johnson’s “white supremacist views and activities,” the letter read, “make him an inappropriate namesake within any education or cultural institution that purports to serve a wide public.”

Days after the letter was sent, the dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design said the school would rename a house designed by Johnson in the 1940s.

The building, known at the time as the Philip Johnson Thesis House, is now simply referred to by its street address in Cambridge. (The Johnson Study Group reissued its letter in January to acknowledge Harvard’s response.)

Until the opening of “Reconstructions,” MoMA remained silent on Johnson’s legacy, which is deeply entwined with its own history.

Johnson helped found the museum’s department of architecture and design he served as its head from 1932 to 1936, and again from 1946 to 1954. He was named a trustee in 1957, and maintained a close relationship with the museum for nearly five decades until his death in 2005.

“To move forward with the exhibition thoughtfully, honoring the communities that the artists and their works represent, we feel it’s appropriate to respect the exhibition design suggestion and cover the signage with Johnson’s name outside the architecture and design galleries on an interim basis,” a representative from MoMA told Artnet News.

The spokesperson said the museum has undertaken a “rigorous research initiative to explore in full the allegations against Johnson and gather all available information. This work is ongoing.”