Back in 2017, in the wake of the reverberant protests around Donald Trump’s first, nasty attempt at a “Muslim ban,” MoMA did something extraordinary. As a curatorial gesture of solidarity, it inserted works by artists from Muslim-majority countries or with Muslim backgrounds into the heart of its Modern galleries, where it keeps the crown jewels. Thus, a large canvas by Iranian painter Charles Hossein Zenderoudi suddenly joined Matisse’s The Dance; a small black-and-white work by Sudanese modernist Ibrahim El-Salahi appeared in the Picasso galleries.

Judged as a curatorial act of protest, MoMA’s gesture felt exciting and—grading on a curve for a mega-institution with a byzantine bureaucracy—bold. Sure, as an act of meaning-making, it probably didn’t do full justice to the independent creative worlds of the artists summoned for its purpose, inserting them into someone else’s history and removing them from their own chronology and context. The very need for the gesture highlighted an absence that had otherwise been there, in the heart of the story of art being told: Modern art, as told by the Museum of Modern Art, was the story of émigrés, exiles, and outcasts—but mainly ones from Europe.

But it was an emergency gesture, responding to a sense of crisis and the need to do something that felt substantial.

I bring this up because here we are, two years later and on the far side of the museum’s forceful $450 million building expansion and a far-reaching curatorial attempt to rethink the logic of the permanent collection galleries, opening them up to tell a more inclusive and global story, and the results feel strikingly similar. For all the evident long hours and agonizing hard work building up a new system, the new story of art that MoMA is telling still feels curiously similar to that earlier emergency intervention—reactive and provisional.

Tearing It Down to Build It Up Again

If you’ve read anything about the reinstallation of MoMA’s collection, you will know the basics: film, photography, design, and architecture holdings have been integrated into the heart of the story, so that building maquettes, Modernist floor plans, stills from classic films, troves of vernacular photos, and looping film clips alternate with the conventional displays of painting and sculpture. An attempt has been made to add more women artists, minorities, and non-Western voices throughout, as well as to break down, to a certain extent, the membrane between “insider” and “outsider” art.

The “Surrealist Object” gallery at MoMA. Image: Ben Davis.

It’s all broadly chronological, still, with art from the 1880s to to 1940s up on the fifth floor, the 1940s to the 1970s on the fourth, and the post-1970s contemporary down on the second. But it no longer marches to the rhythm of the art historical movements familiar from old college art surveys.

Francis Bacon’s Painting (1946) and David Alfaro Siquieros’s Collective Suicide (1936) in the “Responding to War” gallery. Image: Ben Davis.

Instead there are more thematic rooms. Sometimes the themes are pegs to hang a familiar MoMA-approved cluster of artists on, e.g. “Readymade in Paris and New York,” “Surrealist Objects,” “Planes of Color.” Sometimes these are more allusive and deliberately mushy, allowing for conjugations of works you might not think about together: e.g. “Responding to War,” “Stamp, Scavenge, Crush,” “Inner and Outer Space.” As art history, it feels lumpy: different thoughts and strategies are happening from gallery to gallery.

Are there highlights of this new installation? Are you kidding me? The highlights are too numerous to list!

Morris Hirshfield’s Tiger (1940) and William Edmondson’s Nurse Supervisor (ca. 1940). Image: Ben Davis

In the Modern quarters, I think of the sense of unsettled innovation conveyed by the “Early Photography and Film” gallery, which puts the whole era’s fine-art experiments with fragmentation into multimedia context; the entirety of the “Surrealist Objects” room; the institution’s renewed faith in the oddly incredible paintings of Morris Hirshfield (“Among twentieth century American paintings I do not know… a more unforgettable animal picture than Hirshfield’s Tiger,” MoMA’s founding director and czar of Modernism, Alfred Barr, once raved of the self-taught artist’s work).

Wilfredo Lam’s The Jungle (1943) and Maya Deren’s A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945). Image: Ben Davis.

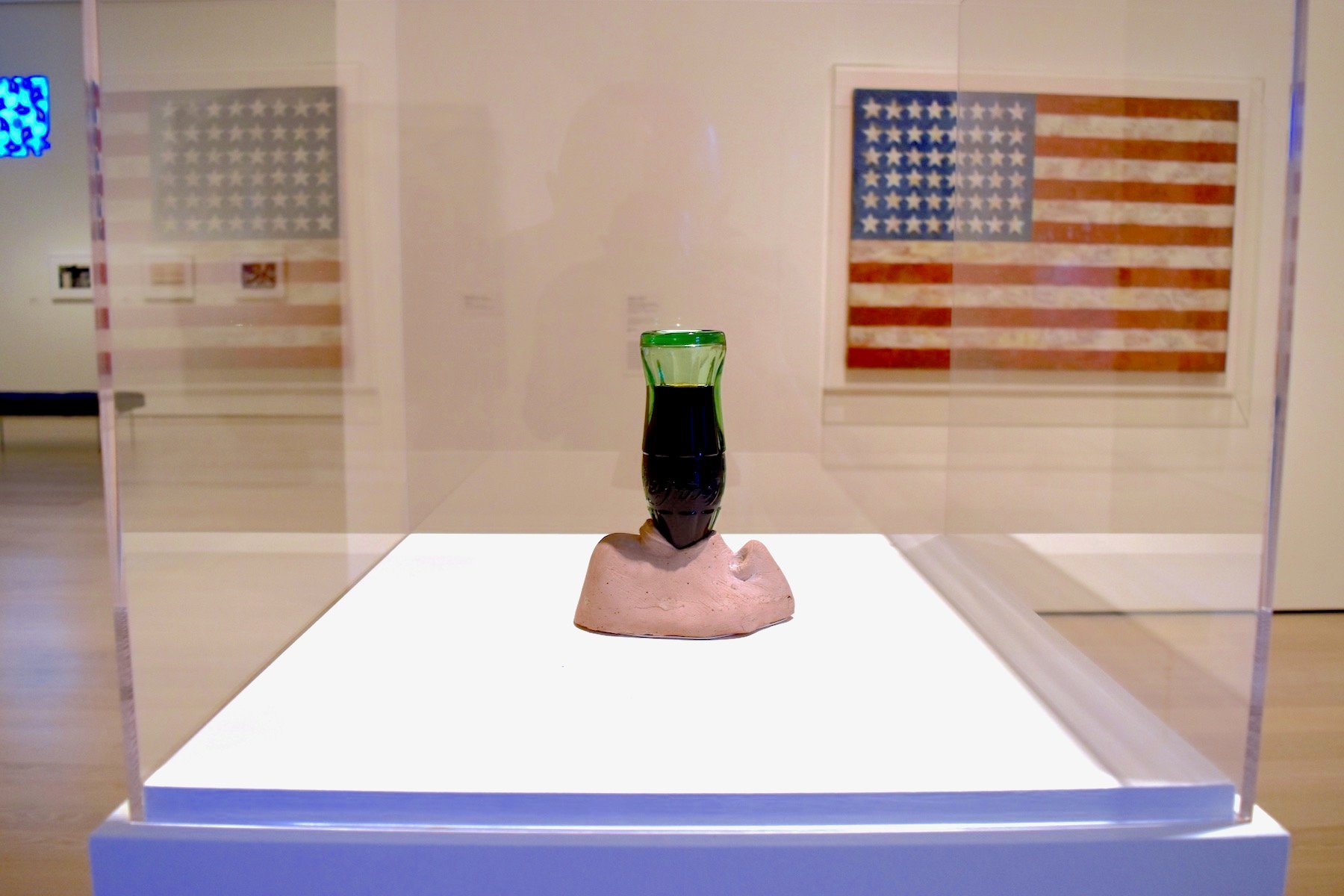

In Postwar, I think of Wilfredo Lam’s the Jungle (1943) and Maya Deren’s experimental dance film put in conversation (1945); Marisol’s small and unforgettable sculpture of a disembodied face being force-fed a bottle of Coca-Cola placed before a poker-faced Jasper Johns flag; the eloquent grit of Japanese photographer Daido Muriyama’s photos; a case of Ibrahim El-Salahi’s intricately drawn notebooks from his time in prison.

Doris Salcedo’s Widowed House IV (1994) and Zarina’s Home is a Foreign Place (1999). Image: Ben Davis.

In Contemporary, there’s Zarina’s beautifully cryptic and personal portfolio “Home Is a Foreign Place,” a kind of visual poem; the great post-Pictures artist Gretchen Bender’s cataclysmic multichannel video installation Dumping Core; the heady but righteously visceral dance film from Wu Tsang, We hold where study.

But then, of course, any show with these resources and this much curatorial talent behind it will have individual highlights. It’s a highlights show.

So let’s talk about what’s weird about the thing as a whole.

A New Art History?

The idea of needing to rethink the story of modern art has been very much in focus in recent years. In 2016, the Haus der Kunst’s huge and ambitious “Postwar” show, for instance, set out to do exactly that, seeing how the 1940s to the ’60s moment looked artistically, if you opened the aperture of art history to let in the light of multiple modernities.

“To soldier forth with this endeavor, the weight of ‘canonical’ art history must first be shrugged off, let fall, gracefully, by the wayside,” the late curator Okwui Enwezor wrote in that show’s massive catalogue tome. “That does not necessarily mean casting it aside in toto, nor abandoning some of its many important insights. But it is part of this exhibition’s mission to acknowledge and identify the persistent blind spots of that history, and the Eurocentric limits that it places on artistic activists outside Europe and North America.”

I think that’s a pretty good program. But this is very much not how material manifests in this MoMA reinstall.

The sharp features of the MoMA-approved history may have expanded to offer a more detailed topography—but, really, it is still the same general landscape. The river of history still runs from Paris through New York to the ocean of “the global,” only now with a few extra tributaries.

Tarsila do Amaral’s The Moon (1926), Constantin Brancusi’s Blonde Negress (1933), and Fernand Léger’s Three Women (1921-22).

Indeed, not one but two galleries are devoted to Paris as a meeting place for the global avant-garde, “Paris in the 20s” on the fifth floor and “In and Out of Paris” on the fourth. This proves to be one way to retell the same old story while still diversifying the palette. The former gallery, for instance, gives us not just Brancusi and Léger but also a canvas by Tarsila do Amaral, the towering, troubling Brazilian artist (recently given a solo show at MoMA).

Paris is part of her story, but Brazil is where its impact is. Particularly given the stakes of the “Antropofagia” (or “Cannibalist”) movement she helped initiate, which was all about advocating for a unique Brazilian aesthetic that blended cultural influences, you really want to see her surveyed in a Brazilian art context as well.

Song Dong’s Breathing (1996) and Huang Yong Ping’s Palanquin (1997). Image: Ben Davis.

Meanwhile, the entirety of this new, rethought permanent collection features just one geography-specific gallery dedicated to a non-Western art scene, down in the contemporary section. It is titled “Before and After Tienanmen” and dedicated to Chinese art—which makes good sense, since the rise of China is in many ways the major human event of the last decades. Yet given how seismic the artistic energy coming out of China has been in recent years, this is still a very, very abbreviated showcase, with just five artists.

What is the governing logic here? You have to think of this installation, above all, as a compromise formation reflecting an institution wrenched between two poles.

On the one hand, MoMA’s bread and butter is mass tourism. “Critical works that people travel long distances to see, like Matisse’s Dance, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, the Demoiselles d’Avignon, Monet’s Water Lilies—we’re not going to change those,” the museum’s director, Glenn Lowry, told my colleague Andrew Goldstein.

On the other hand, particularly since Trump’s election, a decidedly mainstream form of cultural consumption for an educated, liberal audience now involves a hyper-awareness of and symbolic atonement for the sins of history. The New York Times is the paper of record for these kinds of gestures, not just with the refreshingly deep historical reexamination of US racism of its “1619 Project,” which had fans literally lining up in Times Square to get special copies, but in its project of writing new obits for women whose accomplishments it had historically overlooked.

Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), Ellen Gallagher, DeLuxe (2004-5), and Roni Horn, Stevens’ Bouquet (1991). Image: Ben Davis.

MoMA’s own reinstalled contemporary galleries, which center feminist critique, black artists, Latin American political work, and queer subjectivity, provides the lens through which its own past history has to be viewed. You can’t just pretend that there was no dark side to European and American history.

Pinioned by these two impulses, some kind of compromise must be reached.

Mostly Monochronology

And so, new voices have been inserted, which is an exciting thing. Yet very often the new voices are quite obviously introduced so that they appear as icons of “inclusion,” very much on the “Muslim ban” protest model. Because the underlying narrative remains intact, it is pretty clear whose story is primary, and who is a supporting character.

Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon on the left, and Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20. Image: Ben Davis.

The most-talked-about example, because it really is so striking, is Faith Ringgold’s vivid painting of a race riot hung to rhyme with Picasso’s ur-modern Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, in a room full of classic-period Picassos. Nearby, a room dedicated to MoMA’s magical, must-see Matisses—The Red Studio, The Dance, et al.—gets the accent of a small red-and-blue abstraction by Alma Thomas. Down in the postwar galleries, the glories of the New York School remain inviolable, but now Mark Rothko is paired with an abstract work by Indian modernist Vasudeo S. Gaitonde.

Vasudeo S. Gaitonde’s Painting, 4 (1962) and Mark Rothko’s No. 10 (1950). Image: Ben Davis.

Introducing the volume Modern Art in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, art historian Eileen O’Brien writes of the need to reject an approach to global modernism whereby “artworks are presented thematically, as if they had no histories or precursors.” This pretty much exactly describes what you get when, say, you pay homage to Korea’s recently hotly discussed Dansaekhwa (“Monochrome”) movement of abstract painting via exactly one 1974 dotted burlap canvas by Ha Chong-Hyun, placed in a gallery dedicated to responses to violence and oppression (“War Within, War Without”).

John Outterbridge’s Broken Dance, Ethnic Heritage Series (ca. 1978-82) and Ha Chong-Hyun’s Conjunction 74-26 (1974). Image: Ben Davis.

Enwezor mentions a “heterotemporal” and “heterochronological” approach—which really just means: Give the “new” art histories the dignity of their own spaces and contexts. Do an actual gallery of Japan’s Gutai movement (rather than a single drawing by Atsuko Tanaka mixed in with a bunch of other stuff), or the Bombay Progressives (rather than just that lonely Gaitonde), or Dansaekhwa. MoMA’s thematic approach starts to read like an expedient way not to concede this space.

“On the Modern”

This suspicion is thrown into relief over on the third floor, where you can actually see what another approach could look like in the galleries turned over to “Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction—The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift.”

The temporary installation of mainly abstract Latin American geometric painting reverses the energy field. It presents MoMA canon staples like Piet Mondrian and Aleksandr Rodchenko as guest stars to illustrate influence and affinity. The main story is the tremendous flowering of different experiments with abstraction in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Venezuela, in the postwar period.

Willys de Castro’s Objeto ativo (cubo vermelho/branco) (1962) and Gyula Kosice’s Escultura móvil (1948). Image: Ben Davis.

This is very clearly one story of Latin American art, not the story of Latin American art, conveying a very specific taste. The way that Brazilian Neo-Concretism eventual boiled over into the gnarlier interactive psychedelia of Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark is merely alluded to in the inclusion of Ivan Cardoso’s 1979 film H.O. and some photos of Oiticica’s experiments with wearable art in action; the affiliations of the more zealous Latin American abstractionists to Communism are mentioned, but dutifully. On the whole, it’s a pretty preppy, formal installation.

Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-43) and Jesús Rafael Soto, Double Transparency (1956). Image: Ben Davis.

Nevertheless, “Sur moderno” tells a relatively focused story from outside the usual axis of MoMA’s Modernist geography, without lapsing into thematic indistinction or pseudomorphism. By its example, it illustrates the degree to which the underlying logic of the main reinstall, even with all its many sincerely interesting new presences, recalls Visconti’s famous quip representing the plaint of a fading aristocracy: “everything must change so that everything can stay the same.”

Eugenio Espinoza, Untitled (1971) and Claudio Perna and Eugenio Espinoza, La Cosa (Médanos) (1972). Image: Ben Davis.

But at the same time, “Sur moderno” also cuts against the fantasy of institutional omnipotence, i.e. smart aleck complaints like mine that imply that at any moment the all-powerful MoMA can just tell whatever story it wants. The point this show clearly projects is that MoMA could not have told this new story without the largesse of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, a woman with the resources of “one of the largest privately held media fortunes in the world“—just as, over in the contemporary galleries, the handful of works from the Congo all hail from a single generous gift from Jean Pigozzi. The canon is not just a mental structure to be wished away. It is a calcification of tremendous amounts of historical wealth.

Cheri Samba, Problem of Water (2004) and Bodys Isek Kingelez, U.N. (1995). Image: Ben Davis.

A Permanent Crisis in the Canon

“We know that there are dozens of issues that were left on the table when we made hard decisions about what to show in the museum,” Lowry cheerfully concedes. You could go on listing things this installation does not do justice to, how even without accounting for a global story, MoMA’s US story is quite New York-centric. (Off the top of my head: Recently resonant movements like LA’s Light & Space, Chicago Imagism, AfriCOBRA, and the Washington Color School are all just rumors here, and even Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1943), most certainly a painting “people travel long distances to see,” does not make this christening.)

With its expansion, MoMA has never been physically bigger. Because of the present’s intensified awareness of exclusion and the general expansion of the cultural conversation, though, it has also never looked smaller, more particular, less universal.

The “At the Border of Art and Life” gallery. Image: Ben Davis.

Thus, the most radical gesture of the new MoMA permanent collection display may be that it is not permanent. The decision to turn over the galleries every few months to rethink juxtapositions and react to new conversations is a strategy, both wise and expedient, to forestall any criticism about lacks or absences.

Since, as Lowry notes, the crowd favorites will remain on view, it’s possible to argue that, in a way, the traditional Modern stars are rendered even more monumental by this dynamic scheme, standing as the traumatic material that everything else constantly reorders itself around to justify. It is also possible to be really conspiratorial and say, “Oh great, just when finally the canon starts to get seriously opened up—whoops, no more canon!”

Dan Flavin, untitled (to the “innovator” of Wheeling Peachblow) (1969), Anne Truitt, Catawba (1962), Rasheed Araeen, (3+4)SR (1969), and Donald Judd, Untitled (1967) in the “Breaking the Mold” gallery. Image: Ben Davis.

This really is too cynical. With finite space and a near-infinite task, there is probably no other way to do it. In essence, it is as if the quicksilver, incessant stream of commentary on the internet has poured against the collection, annealed with it, and rendered it into a new and more pliable form. The sense of crisis-response in MoMA’s “Muslim ban” intervention has been rendered institutionally permanent. In an age of continual news upheaval, what it takes to stay feeling relevant and meaningful is continual upheaval in art history.

But how this is done matters to me a lot! In a gesture of pedagogical populism, MoMA has banished the traditional terms like “Pop,” “Abstract Expressionism,” and “Dada” from its presentation. I am sure they have the data to back up the fact that these labels seem off-puttingly jargony to new audiences, with the more loose and conversational themes better suiting some measure of visitor engagement.

The “Circa 1913” gallery with Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913). Image: Ben Davis.

I’ve been thinking that the revisionist art historical blockbusters of recent note point the other way, though. Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim, or “We Wanted a Revolution” at the Brooklyn Museum, or “Radical Women” at the Hammer all have their echoes in this retooled display. But what each of these shows proved to me was that audiences will absorb a heck of a lot of complexity and context—as long as there’s a human story that feels resonant and relevant. Presented as trophies in incidental rhymes with other things—as, for instance, when the now-sanctified Hilma af Klint’s spiritualist-inspired painting is paired with the Futurists’s technophilic (and fascist-sympathizing) art in the MoMA’s new “Circa 1913” galleries—I just feel that artworks lose that hard-earned human depth.

You shouldn’t take the triumphs of this new display for granted. I’ve spend more than 10 hours in it, and that’s not enough to fully see all the great things there. It’s the product of a lot of work, and navigates problems that can’t necessarily just be undone with a wave of the magic “good curating” stick.

But if a time of uncertainty and acceleration isn’t going to deplete these objects, then the loosening up of history is a mistake, I think; history and context are more important than ever as a counterweight. That may mean fully giving up the residual fantasy of telling a universally resonant history, so that the different, specific stories that can be told actually get enough space to make their full case, in the time they have—if that’s possible.