Each week, countless articles, think pieces, columns, op-eds, features, and manifestos are published online—and any number cast new light on the world of art. Each Friday (when I can!), I pick out a few recent pieces that might inspire some larger discussion.

“Goodbye, Guy on a Horse” by Carolina A. Miranda, Los Angeles Times

Statues have been falling everywhere in the past month, amid the ongoing anti-racist protest wave. These topplings have turbo-charged another, parallel conversation about what should go up in their place. Here, Miranda surveys a broad selection of projects to get a sense of how the changing conversation about who gets memorialized is also changing what monuments look like.

The idea of a break with classical forms of monuments is not entirely new. Maya Lin’s powerfully minimalist Vietnam War memorial, derided as the “black gash of shame” in its time by critics who insisted on putting up a parallel figurative monument depicting GIs nearby, casts a long shadow in terms of this conversation. Nevertheless, Miranda argues that this moment may represent the “swan song” for the style of figurative sculpture that has long dotted city squares.

Statue of three armed soldiers at the Vietnam Memorial on the National Mall, Washington, DC. Photo by Robert Knopes/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

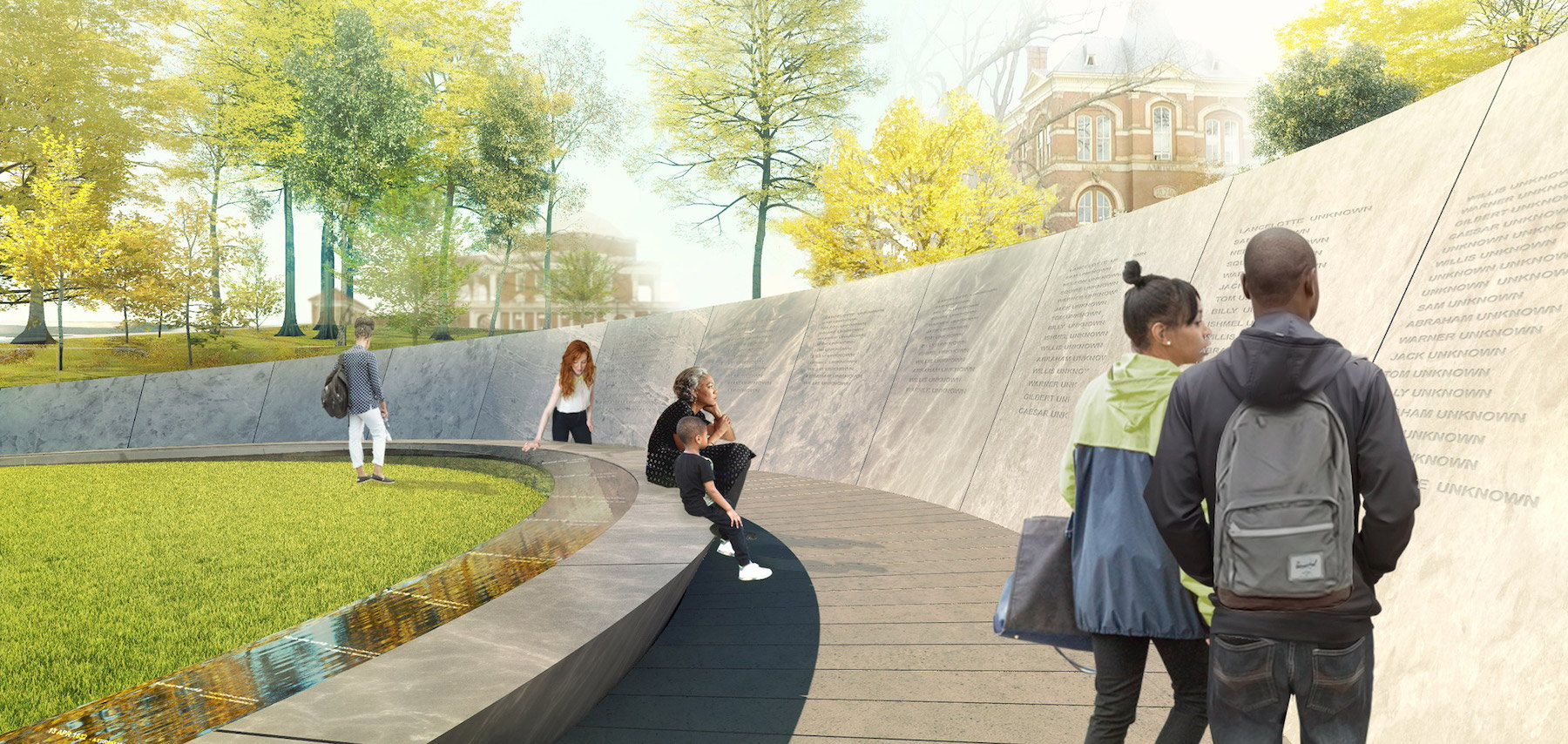

When it comes to present-day sensibilities, Miranda looks to the University of Virginia’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, built to reckon with the institution’s entanglements with slavery. It takes the form of a raised stone ring in the ground, with all the known names of enslaved workers who built the university inscribed.

The article makes me think that the new monument movement represents four parallel shifts in perspective, each flowing into the next, around ideas of history, choice of subject, conception of authorship, and symbolic form.

In terms of ideas of history: the 19th century, when the US’s national identity was forged and so much of the classically inspired heroic monuments went up, was marked by Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle’s so-called “Great Man Theory of History.” World events, in this view, were driven by exemplary and heroic individuals, “the modelers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain.” So you got images of singular leaders celebrated as avatars of civic virtue.

But Great Man Theory is out now and “People’s History” is in—that is, history told not from the point of view of world-moving individuals, but from the point of view of the excluded and marginalized, of social movements that were often antagonistic to the people in power.

That affects the choice of subject matter. While some new monument initiatives have focused on adding tributes to more diverse individuals, it seems to me that that gesture actually tends to sit oddly with the underlying spirit in which this rethinking of public space is happening. So many of the new monuments focus not on individuals, but on events; and not on exemplary heroic moments, but on instances of injustice whose memory is being reclaimed.

Thus, one of Miranda’s case studies is a planned monument to the events around the “Sleepy Lagoon Murder” of 1942, when the unsolved death of José Gallardo Díaz at an LA swimming hole touched off a moral panic about Mexican gangs that led to the wave of anti-Mexican vigilantism known as the Zoot Suit Riots. The proposal reflects a keen sense of the need to honor the entire context of a segregated LA that gave birth to that chain of events. As artist Arturo Ernesto Romo tells Miranda about the project, “[t]o reduce an incident like that down to an individual thing, it doesn’t do justice to the way that any human experiences and events play out.”

Following directly from changed ideas of both history and choice of subject, two further effects stand out to me. One is that this different picture of the past also changes the way the role of the artist involved is imagined. The Great Man theory of History logically rhymed with the Great Artist idea of art history, and thus its monuments tended to be commissions from prestigious professional individuals. The new monuments tend instead to be framed more as the result of lots of community input and collaboration between multiple authors, credited as a team.

Rendering of UVA’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers. Image courtesy Höweler + Yoon Architecture LLP.

The other shift is in the function of the site of the monument itself. “People’s History” is sometimes also called “History From Below.” And, symbolically, while traditional monuments give us figures on pedestals that you are meant to literally and figuratively look up to, the new monuments tend to be much more horizontal, serving as garden-like social spaces or stages for ceremonies. In the case of UVA’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, it is meant as a place to “gather, reflect, acknowledge, and honor.” The Sleepy Lagoon monument is planned to reflect the “restful spirit of a swimming hole.”

In Miranda’s piece, Cameron Shaw, chief curator at the California African American Museum, offers an example that brings all these threads together in a clarifying way:

When I start to think about the types of monuments that interest me, it’s the collective ancestor altar. That is a form known by Angelenos: a public, large-scale site where people can honor the people who came before us, the native land, the people who came after. That’s something we see throughout the city and because of celebrations like Día de los Muertos, it’s very familiar. In my mind’s eye, it has photographs, it has screens that play images of folks’ ancestors, multiple artists contribute to the vision, and there is a pilgrimage piece in which Angelenos can come from all over and contribute many different images and many different rituals.

“American Degeneracy” by Michael Lobel, Artforum

Frederick Wellington Ruckstull, South Carolina Monument to the Women of the Confederacy (1912). Image courtesy of the Historic Columbia Collection.

This is popular art history at its best: Lobel digs into the history of The Art World, a 1916 magazine edited by one Frederick Wellington Ruckstull (1853–1942), dedicated to spreading the idea that modernism was a sign of civilizational decay and moral corruption. The reason why this near-forgotten publication is newly relevant is because it illustrates the art-historical bridge between two moments: Confederate monument building and fascist demonization of modern art.

Ruckstull was a prominent scholar and member of the early 20th-century New York art scene (his sculpture Evening (1887), a sleepy, idealized female nude, is on view at the Met). It turns out that he was also a major player in shaping the look and ideas of the Confederate monument movement: “In the two decades or so leading up to his writings in The Art World, Ruckstull had devoted his artistic career to developing a detailed symbolic sculptural language for the Southern ideology of the so-called Lost Cause.” Later, his extravagant anti-modern diatribes following the 1913 Armory Show are thought to have influenced Nazi ideas of “Degenerate Art”—very much a parallel to how the US’s Jim Crow laws and white suprematist terror directly inspired the ideology of Hitler’s Germany.

“Art is Not Revolutionary Unto Itself; It Is People Who Are Revolutionary” by César Montero, puntorojo

Check out the crisp, committed graphic work of César Montero, spotlighted here in puntorojo, a new magazine dedicated to “the current generation of Mexicanx, Chicanx, Latinx, transborder, and transnational radical thinkers, workers, scholars, activists, artivists, historians, and other commentators.”

Montero’s works have hard-hitting verve. This selection makes me look forward to the upcoming online exhibition “Desde Abajo: La Gráfica Libertaria de César Montero (From Below: The Liberatory Graphics of César Montero),” set for August from Mata Art Gallery—though based on his artist’s statement here, they might be best seen on the streets in solidarity with tenants on rent strike or Black Lives Matter.