The New York Times review of Paula Rego’s Tate Britain retrospective, published on July 7, begins: “Paula Rego is the kind of artist who paints a soldier in a leopard-print gimp mask, a little girl shaving her pet dog and the devil’s wife in nipple tassels.” This sentence might have read: “Paula Rego, one of our greatest contemporary figurative artists, draws harrowing, celebratory, and revelatory portraits of women that have redefined the practice of drawing, narrative figuration, and feminist portraiture.”

I met Paula Rego as an undergraduate at Yale in 2001, when her work was included in a show at the Yale Center for British Art. She approached me in the lobby of the museum before her talk because I had a flask of whiskey that I was covertly drinking from. As an agoraphobic, she entreated me for a sip.

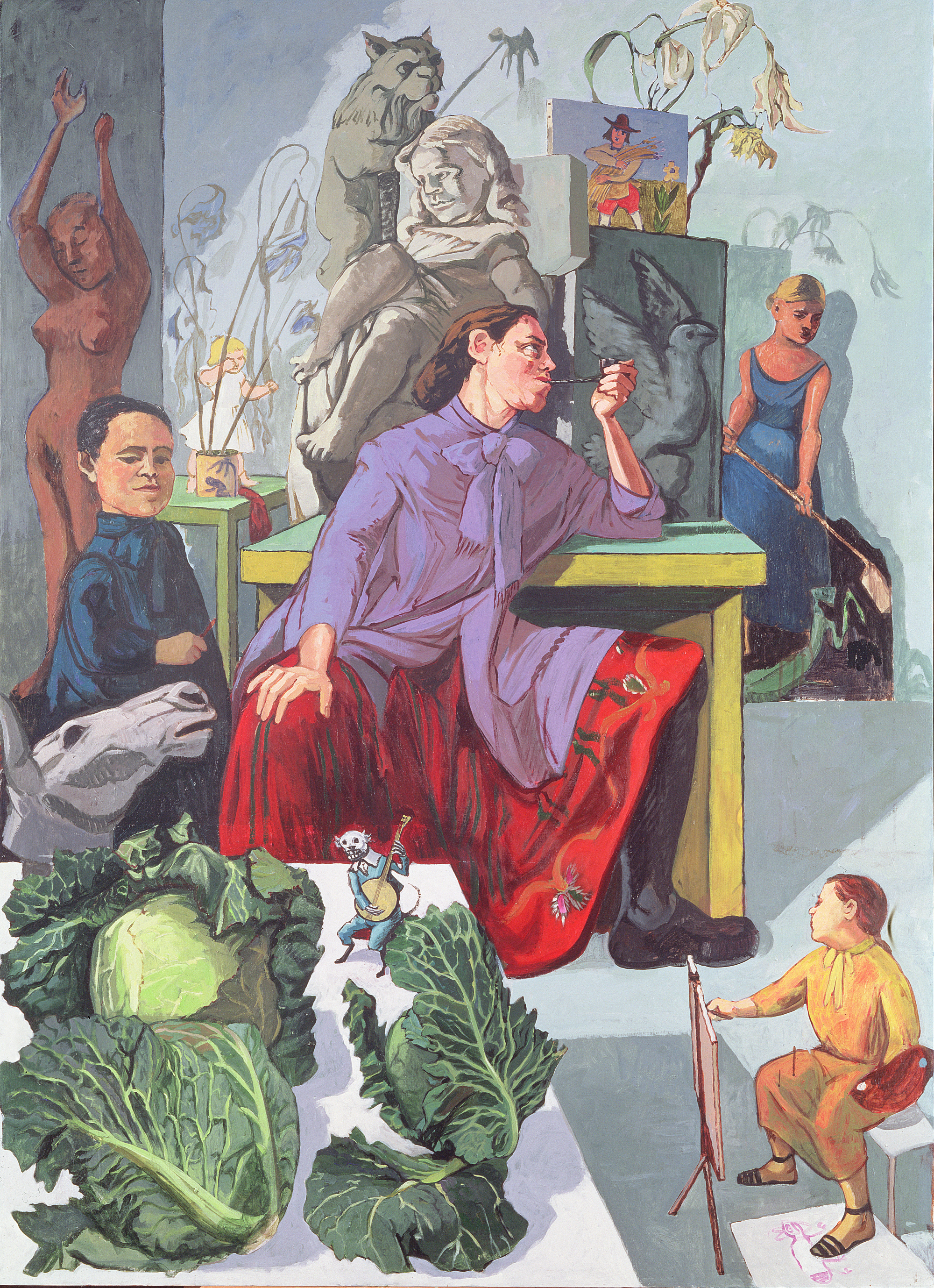

Portuguese-born British painter Dame Paula Rego during the opening of her show at the Marlborough Gallery, New York, 1996. Photo by Rita Barros/Getty Images.

I was an earnest young artist, and it was my habit to carry photographs of my paintings. I nervously waited to share them with Paula after her talk. She kindly looked at each one and invited me up to the director’s office for a drink. We connected over shared interests in feminist portraiture and the intersection of narrative, the female body, violence, and sexuality, as well as a bawdy vocabulary.

We began by writing letters, which would span the next decade and a half; letters turned into visits, in her studio in London most often, but also walking New York streets and museums. From Paula, I learned that drawing could be primary, and that stories that show women as they are—full of complexity, brutality, and grotesque sensuality—were ones that I needed to tell.

Paula shared that she had been turned away from the Slade, a loci for many of the School of London artists, and also where I learned to paint, because she wasn’t considered a good enough draughtswoman. Eventually she attended, but remained in the shadow of her husband, Vic Willing.

Paula Rego, Cast of Characters from Snow White (1996). Private Collection, London © Paula Rego.

In the beginning, she painted vomiting monkeys and vengeful, castrating rabbits, as well as abstract worlds disintegrating into collage. Her imagination conjured dark shadowy spaces where dignity erodes and people transform in daylight into their bestial selves. More than nightmarish surrealist tales, Paula captures the body in both activity and decay. Injustice floods through the violent pastel marks of her surface, and like many women who came before her, fairy tales and stories were the cloak to her dagger.

There is a clear and meaningful through line from Rego’s early abstraction, filled with political rage, fragmentation of space, and personal chaotic narrative, to her “Dog Women” series from the 1990s, whose bodies seem to have swallowed all of this anger and desire in a protest for freedom.

Visitors attend as Tate Britain opens UK’s largest ever retrospective dedicated to Portuguese visual artist Paula Rego at the Tate Britain on July 05, 2021 in London, England. (Photo by Tim P. Whitby/Getty Images)

It is this rage, protest, and female sensuality, encapsulated in her feminist portraits, that still prove controversial and uncomfortable. A perfect illustration is the New York Times review by Eleanor Nairne, a curator at the Barbican Gallery. In one sentence at the beginning of her review of over six decades of drawing, painting, collage, and printmaking, Nairne instructs the reader to dismiss the past three decades of Rego’s “recent” work. It is her “exuberant, otherworldly early work, rather than the gritty naturalism of her recent pastels, that lingers powerfully in the mind.”

It is a reviewer’s prerogative and job to cast judgement as they see fit. But I believe this is a fundamental misreading of what makes Rego important. Her turn to drawing in pastel in her 40s, with such ravaging portraits as Dog Woman (1994), marked her coming out. I remember seeing some of these large-scale pastels at Yale for the first time, stunned, speechless, wrecked. I didn’t know drawing could be that big, that aggressive. I had never seen such audacious and free images of women.

Paula Rego, Dog Woman (Pastel on canvas, 1994).

By contrast, Nairne describes these women as “hysterical,” “sullen,” and “lone.” How could Rego’s women, transmitting pain and a lifetime of injustice, be reduced to words that men have used to dismiss women for centuries?

Nairne also says the depictions feel “muted and reminiscent of other London School painters, most notably Lucian Freud, who taught at the Slade when Rego was a student there.” Haven’t we come further than the time-worn, patriarchal trope of defining women artists against their male peers? Rego made feminist portraits; Freud made portraits of flesh. In Nairne’s simplification, Rego’s work is lost.

Installation view, Paul Rego, at Tate Britain.

These sweaty portraits presaged the squatting women in her abortion pictures, pictures she made in support of the legalization of abortion, which came to her native Portugal in 2007. Paula, now 86, grew up under the Salazar regime of the 1930s and made what was personal political, and vice versa.

It is from Paula that I learned about fairy tales as historical markers of women’s oral histories, and that figurative drawing could so beautifully capture a theater of the absurd, as well as document and protest women’s place in society. Paula’s remarkable facility and imagination are on full display in her graphic work: lithographs, etchings, aquatints, and of course, drawings. Her line, so lyrical, self-assured and playful, belies the unflinching narratives she chooses and the horror she wants to show you.

This is perhaps the review’s gravest oversight—and a widely held bias throughout the commercial and institutional ranks of the art world. Nairne fails to acknowledge one of the main subjects of Rego’s life’s work: drawing. To do so neglects the genius of both her imagination and her hand, as well as the gravity of her approach to stories as a humanist and feminist through the lens of drawing. It is astonishing that Nairne also does not acknowledge Rego’s involvement with printmaking, which has spanned over six decades. Rego is widely held to be one of the finest printmakers alive. Neglecting Rego’s graphic work and any acknowledgement of her powerful hand in drawing feels much worse than a misreading; it feels like an act of erasure.

The UK’s largest ever retrospective dedicated to Portuguese visual artist Paula Rego at the Tate Britain on July 05, 2021 in London, England. (Photo by Tim P. Whitby/Getty Images)

Rego’s large-scale pastels of her “Dog Women” use drawing to mirror the interior complexity and rawness of women; these are her finest works. It is not surprising that, to some (including Nairne), they are the most menacing and thus, disposable. Female sexuality, when objectified, is still easy. Rego, however, commands all of its ugliness: the ripping flesh, hairy bodies, thick calves, and uneasy grimaces and, like a sorceress, transforms what has been deemed depreciative in women, into what endows them with agency.

Rego’s surfaces are stand-ins for the body, and at times, I suspect as a drawer myself, for her own. The act of drawing is a sensual ritual: bringing forth life by squeezing, rubbing, touching, creating and destroying bodies. Sensuality intertwines with mark-making in all of Rego’s work, and nowhere is it more important than in her pastel drawings from the 1990s onwards. Her focus on the bodies and roles of women in narrative scenes serves a vital function: it gives a literal presence to women who have not seen themselves as the leading actors of their own stories, and allows them to be imperfect heroines, elevating feminist portraiture.

Natalie Frank, All Fur III, (2011–14). Courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art.

During a visit to her studio in 2011, Paula encouraged me to consider drawing the Grimm’s fairy tales. She said that, if she had more time, she would have drawn them. At the time, I had not yet turned to drawing, gouache, chalk, nor pastel, nor had I begun working from literary narrative. Paula talked to me about trusting my imagination, and creating the worlds that I wanted to inhabit.

In her 40s, she revolutionized feminist portraiture, and prompted me, in my mid-30s, to turn to drawing. That practice has now spanned a decade and includes books (one of which, on the Grimm’s, I dedicated to Paula) and museum shows (including a just-opened drawing survey show co-organized by the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art and the Kemper Museum). In 2019, I worked with a team to design the sets, costumes, and animations for a Grimm’s Ballet at Ballet Austin, in which every element was drawn.

Paula Rego, Inspection (Rosenthal 195) (2001–2).

Paula cleaved open a space for artists to tell stories, to draw—a space where women, especially, can explore the ways in which sex and violence intertwine. During our last visit in her studio, she asked me to undress and don a black, ruched, Victorian dress and pose. We had lunch and went about our afternoon.

Months later I received a package in the mail, a lithograph of me, hawkish, offering Jane Eyre to be inspected by Mr. Rochester. Six months later, another package arrived, this time much smaller, and in it was a beautifully wrapped set of Jane Eyre postage stamps made by the British government, with my evil profile. In true Paula fashion, she insisted that the women be made into first class stamps, the men, second. In her revolutionary drawings, painting and graphic work, she has always put women first.

Natalie Frank is an artist in New York.