Two sisters, one consoling the other. Headphones and a microphone collaged onto a canvas. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, majestic in a black robe. These paintings spoke to my soul. I saw them all at San Quentin State Prison, where both the artists and I are serving life sentences. I thought the world needed to see their work, too.

Most art created by people in prison stays locked behind bars, only seen by a captive audience. In rare cases, an exhibition like MoMA PS1’s “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” organized by curator Nicole Fleetwood, brings the work to the outside world.

But what about artists in prisons across the United States who don’t have curators coming to visit them? How can their talents and voices find a way into museums? Why does it take someone from outside to decide what the public should see? And what happens when a pandemic keeps visitors away indefinitely?

The answer is enlisting a curator who resides inside the prison.

Over the past two years, I have taken on this role several times, even before I knew what it meant to be a curator. The experience has taught me that in the same way that incarcerated people have unique stories to tell as artists, they also bring particular skills as curators—and insight into the art that others might lack.

I first acted as curator for “Meet Us Quickly: Painting for Justice From Prison,” an exhibition at the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco in 2020. It featured the work of 12 men incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison.

My honorary title of curator came about because a Jewish lady was determined to work with a system-impacted Black person on decarceration. Jo Kreiter, an aerial dance choreographer, experienced the prison industrial complex through visiting her husband in federal custody. His mistreatment inspired her to use dance for activism.

She came up with the concept “The Decarceration Trilogy: Dismantling the Prison Industrial Complex One Dance at a Time.” Part one, The Wait Room, focused on the experiences of women visiting loved ones in prison. Part two was geared toward Jewish people helping Black people end mass incarceration—Meet Us Quickly With Your Mercy. For part two, she wanted to work directly with a Black writer and social justice advocate. Her quest led her to me.

The entrance to “CounterPulse,” an exhibition of work by incarcerated artists curated by the author. Photo: CounterPulse.

One day in 2019, I returned to the cell assigned to me to find a letter from her organization, Flyaway Productions. Her pitch envisioned aerial dancers outside MoAD; inside, work by incarcerated artists would be hung on the walls. Jo had me at dancing in the air and ending mass incarceration. I immediately wrote back agreeing to collaborate.

We corresponded regularly, planning long before the launch of part one of her trilogy. That gave us plenty of time to work around the obstacles to communicating with someone in prison: slow mail, 15-minute phone call limits, the difficulty of getting visiting appointments.

With my input, the dynamic behind the exhibition evolved from Jewish people helping Black people to Jewish and Black people working together to end a plague that infects us all.

I quickly gathered paintings from artists with the intent of sending them out months in advance to guarantee they would arrive at the museum on time. Prison is a place of uncertainty, where lockdowns can destroy long-held plans.

At this point, no one said anything about my being a curator. I got involved simply to free the humanity that reformed men painted onto canvases from behind bars. My formal assignments revolved around writing. I wrote a piece called “Pushed and Shoved” about how systems turn people against each other. Jo translated it into a dance and made arrangements for the dancer to visit.

Before she could, San Quentin went on an indefinite COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, canceling all visits and limiting calls to one every five days. All Jo and I had left was mail. Society also sheltered in place, putting the live event in a state of flux.

Jo and I kept writing, and began reading books together. Many of the titles, like Philip Dray and Seth Cagin’s We Are Not Afraid (1988), about three civil rights volunteers murdered by the KKK, were intended to sharpen our knowledge of history ahead of the event.

This reading and writing helped me get through the worst moments of my incarceration. In June 2020, COVID-19 broke out at San Quentin after a botched transfer. The virus spread like gossip, infecting thousands. I got infected and suffered for 10 days. I heard alarms blaring in response to calls of “man down” seven times a day. Friends left the cell block on stretchers and some never returned, death ending a life sentence for burglary.

“CounterPulse,” an exhibition of work by incarcerated artists. Photo: CounterPulse.

In August 2020, Emily Kuhlmann, a curator at MoAD, wrote to commission me to write a statement for the show. She confirmed the exhibit would go on despite the lockdown and would be held online for the 2020 fall season. She also asked several other questions: Did I have a name for the exhibit? Did I want individual artists’ statements presented online? How long did I envision having the works up on MoAD’s website? At the time, I didn’t realize those were curator questions.

I did not know what a curator did or that my role had made me one. They had commissioned me to write. I considered sending out the paintings to be a favor, extending an opportunity to my favorite San Quentin artists.

I thought to myself, should I be paid for my work as a curator? I wondered what curators make. However, prison rules in California forbid incarcerated people from having a career or profession that generates revenue. The only exceptions are for writing and painting. So I asked for more money to pay the artists for allowing their work to be displayed. MoAD agreed and the nonprofit I worked with at the time received enough funds to give each artist a $600 grant.

The online exhibit launched on December 10, 2020, and ended up being extended through March. About 26 articles, including two in the San Francisco Chronicle, covered the exhibit, making it the most press MoAD ever received for a single show.

After that, doors continued to open. In 2021, after COVID conditions relaxed, I acted as a curator for an in-person exhibition at CounterPulse, paired with a performance in which Jo’s dancers flew above the crowd before viewers entered the space to see art crafted by system-impacted people. Then, Kratina Baker, of the nonprofit DreamCorps, contacted me about being a curator for an exhibition coinciding with their sixth annual Day of Empathy on April 5, 2022.

Work in the “Counterpulse” exhibition. Photo: CounterPulse.

For me, being a curator has become a regular thing. But what about people in other prisons across the nation? I wonder about the amazing talent that’s being left off the walls and out of conversations. Knowing that isolation—growing up in neighborhoods segregated by redlines—is a root cause of violent crime, I wonder why we don’t embrace the work of incarcerated artists more.

The best way to embrace that art is through an inside curator because we know each artist and why their work should be featured. My organization, Empowerment Avenue, is currently working on another partnership with Flyaway Productions and MoAD, this time with incarcerated women. Through this project I will help build the capacity for other inside curators. Empowerment Avenue will also be developing an inside curator training guide to normalize the practice.

After all, prison is no excuse for exclusion. We should make room for this work and its remarkable worth.

Art gets its value from its story, as well as from its beauty. Those who have experienced the darkest aspects of this world and still paint light onto canvas have the most insightful stories. Shouldn’t we find more curators who reside behind prison walls to help tell them?

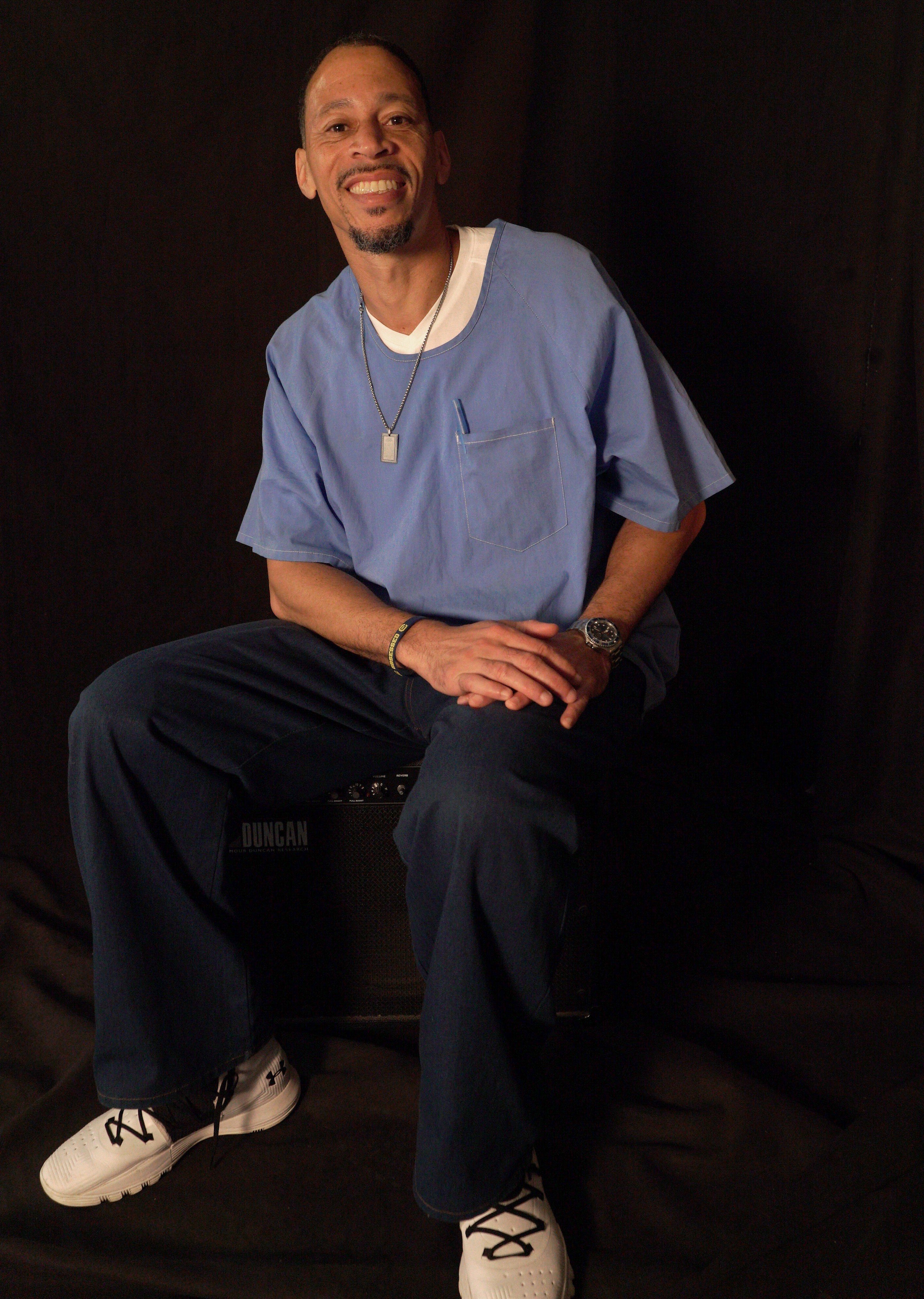

Rahsaan “New York” Thomas is a grandfather, writer, director, curator, advocate, youth counselor, producer, and podcaster, most known for co-hosting the award winning podcast Ear Hustle. He co-founded Empowerment Avenue, an organization aimed at normalizing the inclusion of incarcerated artists, curators and writers in mainstream venues, and he was the curator of DreamCorps Day of Empathy on April 5, in Washington D.C.