Late last month, an Israeli art museum unceremoniously removed a political painting from a group show. Now, dozens of artists in the exhibition are decrying the decision as an act of censorship—and they’re demanding their own works be taken down in protest.

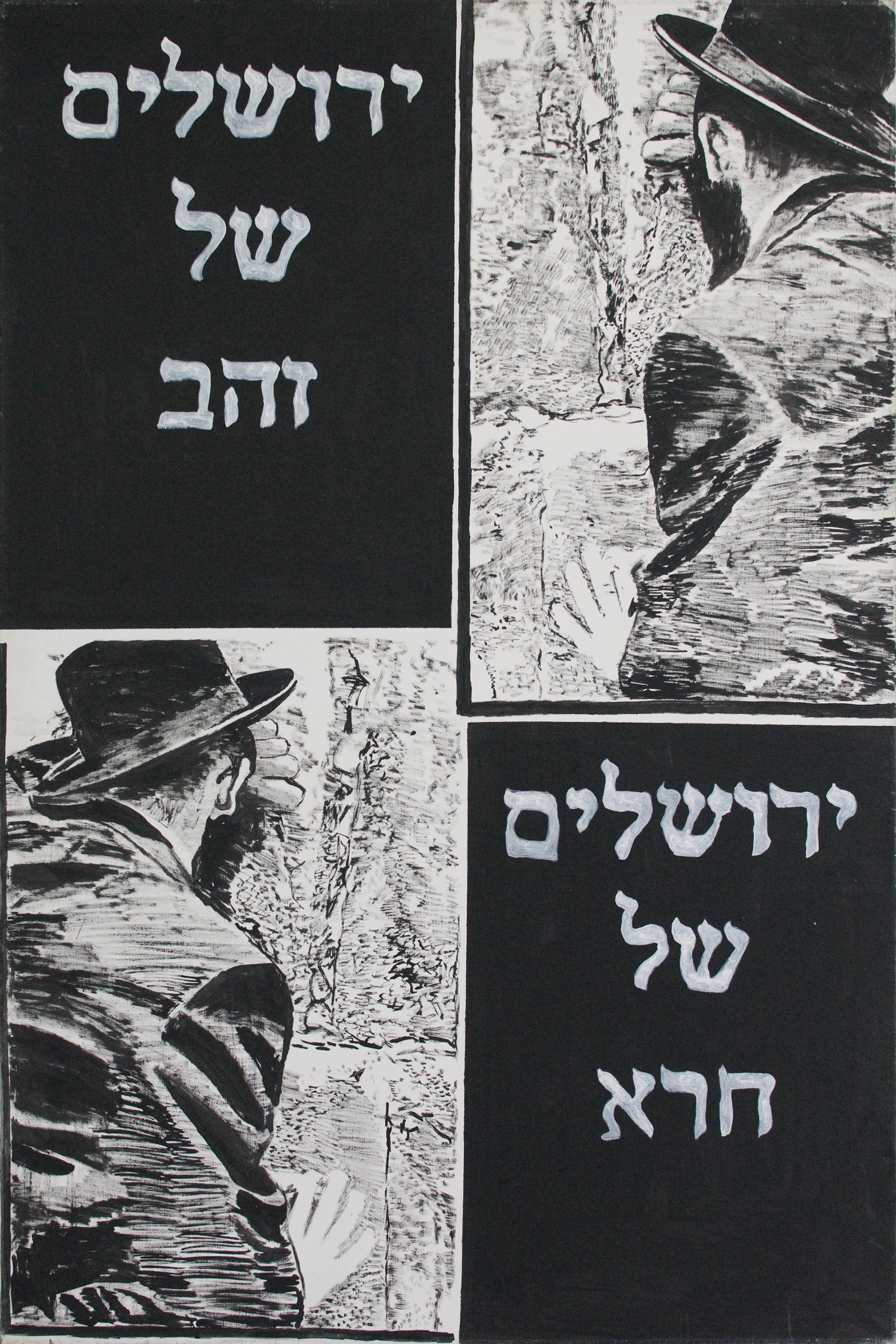

At the heart of the controversy is Jerusalem, a 1997 painting by Israeli artist David Reeb that depicts reverse images of an Orthodox man praying at the Western Wall with the captions “Jerusalem of gold” and “Jerusalem of shit.”

The artwork was included in “The Institution,” an exhibition of more than 60 Israeli artists inaugurating the newly renovated Ramat Gan Museum of Israeli Art outside Tel Aviv.

Days after the show opened on December 23, Ramat Gan Mayor Carmel Shama-Hacohen posted a picture of Reeb’s painting on his Facebook profile, polling his followers about whether the “disgraceful” artwork should be removed from display.

“Jerusalem is a symbol that’s in the heart of every Jew and sacred to all religions,” he wrote in a follow-up post. “Ramat Gan didn’t build a museum for a huge sum of money and will not subsidize it every year to expose its children and others to gutter language.”

Shama-Hacohen subsequently requested that the museum take the painting down, which the institution promptly did.

“I was surprised at the mayor of Ramat Gan’s ridiculous charge that it is ‘a racist painting,’” Reeb told Artnet News in an email. “Of course, it is no such thing. I absolutely respect religious people of all beliefs and denominations and have been fighting racism all my life. I suppose it’s easier for some people to call it racist or antisemitic than to assume responsibility for the dispossession and oppression that we live with.”

After Reeb’s painting was removed, roughly 40 other artists in the the show covered their contributions with black cloth in a gesture of solidarity. Shama-Hacohen then instructed the museum’s administration to remove the cloths, and again the museum acquiesced.

Reeb added that the Ramat Gan Museum’s board of directors “have acted as a rubber stamp for the mayor, who pressured them and threatened that the museum would not be funded if the painting were not removed.”

“Their capitulation to censorship threatens artistic freedoms and more generally democratic rights,” he added.

After the mayor’s move, 43 artists sent an open letter to the museum demanding the immediate removal of their works from the museum.

“Freedom of expression has been severely damaged, the exhibition has become fundamentally flawed, and our work environment as artists has become unsafe and threatened,” the artists wrote in the letter.

Meanwhile, Reeb, working with the Association of Civil Rights in Israel, contested the Ramat Gan Museum’s action in a Tel Aviv district court, requesting that his painting be returned to display. The judge ruled in favor of the museum.

In a statement on its website, the institution said it “regrets the need for a legal decision on this issue. The museum’s professional staff and officials on the museum’s board of directors expressed their views on the fear of a serious violation of the museum institution’s autonomy, the principle of freedom of expression, and the status of the museum. At the same time, we respect the court’s decision and will act in accordance with the ruling.”

The museum also issued a plea to the show’s participating artists.

“Together with you, in transparency and cooperation, we will overcome this crisis and prove that the reopening of the Museum of Israeli Art is a significant and valuable event for the field of art and Israeli society—for its variety of identities.”

Museum administrators could not be reached for additional comment.