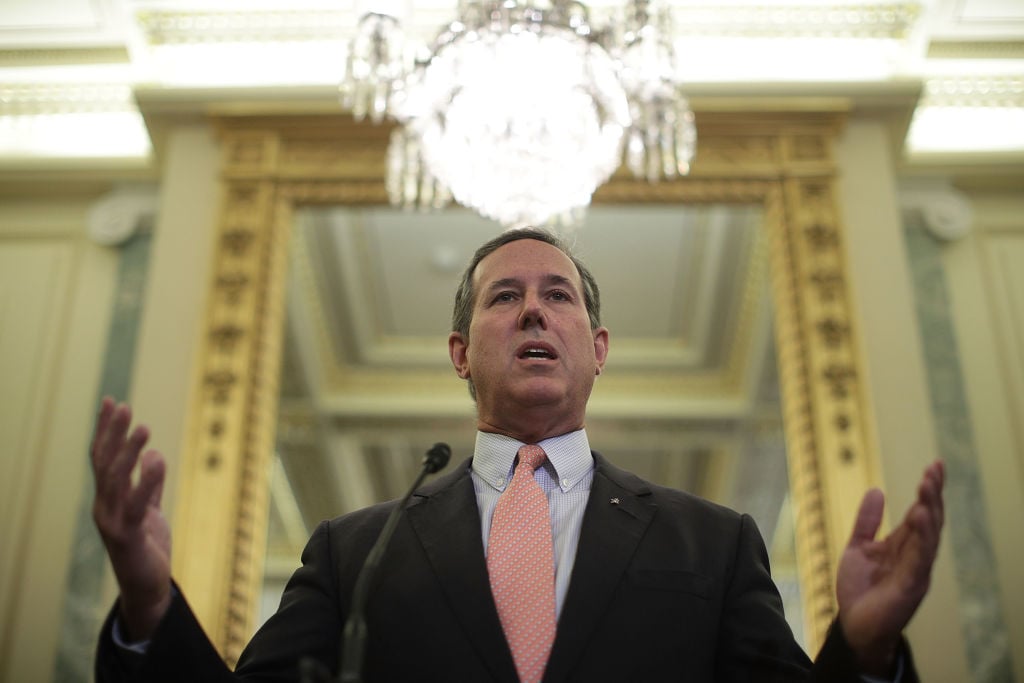

Facing a small classroom, former Republican senator and current CNN pundit Rick Santorum stands at a podium emblazoned with the logo of the Young America’s Foundation, an organization for conservative youth.

There are six young women in the front row, arms crossed, waiting intently for Catholic Dad™ to tell them the story of his “fight for religious freedom,” and he doesn’t disappoint. After a 20-minute preamble about the Civil Rights era, which he describes as destroying the soul of America, Santorum pauses briefly, then says: “We birthed a nation from nothing.”

This disavowal—this denial of the brutal reality of American genocide—repeats ad infinitum among white settlers of all political persuasions. Rick Santorum is not exceptional. His run-of-the-mill white supremacy depends on erasing Indigenous peoples in order to replace us with nothing… with absence. Because if we were never really here, then the Santorums of the world do not have to explain what actually happened to the hundreds of Indigenous peoples whose lands they occupy. They don’t have to explain how we continue to exist, here, now.

In his haste to clarify what he likely sensed was a faux pas, Santorum lets his guard down just a bit: “I mean, yes we have Native Americans, but candidly there isn’t much Native American culture in American culture.” Candidly, he says. The rhetorical leap is telling. We have Native Americans—not “they exist,” but “we” have “them” (we are burdened with them?)—even though their culture has not endured.

Now, candidness is not something we have come to expect from American politicians. Racism, sure. But we are not accustomed to such honesty. Perhaps this is why Santorum’s comments caused a stir online. Here we have Santorum confessing what Indigenous people have known for a long time: for white American culture to exist, ours must be erased.

But we are not so easily erased. The fact of Indigenous presence on Turtle Island has confounded settlers for centuries. In the aftermath of Santorum’s comments, many people have pointed to the role of the Iroquois Confederacy in shaping American democracy, while others have noted our sophisticated agricultural practices and environmentalism.

But rather than try to convince white Americans that Indigenous people exist, or that we have ongoing cultures, or that those cultures are in fact, by definition, “American,” I want to show how Santorum’s admission is part of a long, deliberate history in both settler colonial politics and visual culture that aims to rewrite the story of this continent by erasing Indigenous people.

A Closer Look

In fact, historically, “America” was represented on European engravings, paintings, and maps as an Indigenous woman. Sixteenth and 17th century engravings often portrayed the continents as women—in various stages of undress, surrounded by diverse animal and plant life. By the time the Mayflower left for the “New World” in 1620, this allegorical practice was over a century old.

Take, for example, Allegory of America, from the Four Continents (ca. 1590–1600), a series of engravings designed by Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder. Here, the central figure, a nude Indigenous woman, stands on one leg, supporting her weight with a club, and dons a feather headdress as she gazes languidly at her upturned hand. There she is: America, in terra nullius.

Marcus Gheraerts the Elder, America, from the Four Continents (ca. 1590–1600). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

And so, 400 years later, when Santorum claims that the United States was “birthed from nothing,” one has to wonder, what happened?

The short answer is racism. But the long answer requires a bit of psychology and a bit of jurisprudence, so bear with me. It is not simply easier for white men like Santorum to imagine that the U.S. emerged from nothing. That premise, the blank slate of a virgin continent, is necessary for settlers to promote Euro-American morals. For what moral authority can be based on genocide? It is hard to fathom. Without this blank slate, without this virginia, the horrors of Indigenous genocide would overwhelm the white people who are the inheritors and the beneficiaries of Native elimination. They would crumble under the weight of their own hypocrisy.

International legal scholars describe this use of nothingness to justify the conquest of the Americas as emerging from a series of papal bulls, or public decrees, issued in the late 15th century that granted European nations the right to possess and evangelize lands not belonging to any Christian prince.

Though the term terra nullius, or no man’s land, did not enter the legal lexicon until the 19th century, the right to dominate lands that Christians “found” is the basis of all territorial claims in the Western hemisphere. This regime is often called the Doctrine of Discovery and it still forms the basis of how people like Santorum can claim, without a hint of irony, that we were never even here to begin with—legally, that is.

But even when “finding” empty land, Europeans often represented this place as an Indigenous woman—as in another engraving by Theodoor Galle that depicts Amerigo Vespucci “discovering” America.

Theodoor Galle, New Inventions of Modern Times [Nova Reperta], “The Discovery of America,” plate 1 (ca. 1600). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

A New Allegory of Choice

The allegory of choice shifted from the mysterious Indigenous femininity of the 16th century to an idealized white motherhood in the 19th century. This artistic change took place in tandem with the legal maneuvers that justified the westward expansion of the United States (i.e. Manifest Destiny). Santorum is not wrong when he states that the family was central to the foundational ideology of U.S. nationalism.

He neglects to mention, however, that only white families count in the era of U.S. expansionism. Indigenous families, in contrast, were reduced to reservations, children were stolen or sent to boarding schools, and entire nations (such as my own) endured the forced removal to Indian Territory. Thus, we see rather than an Indigenous woman standing in for America, a new symbolic regime, the ethereal white woman emblematized by John Gast’s 1872 painting American Progress.

Based on John Gast, American Progress (1872). Photo by © CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

This version of “America” is detached from the land, moving across it spectrally, and yet, she carries with her a telegraph wire, a symbol of progress, leading farmers and frontiersmen across a continent.

Here, the allegory of (white) woman-as-progress replaces that of (Indigenous) woman-as-the-land-itself. The land, in turn, is reduced to a stage of Indigenous flight to nowhere, to nothingness. In this image, we see how American white nationalism harnesses white motherhood to do the ideological work of conquest by another name: erasure and assimilation. Indigenous women can have no place in this landscape.

Of course, Santorum is not interested in historical verisimilitude but in the purging of truth from history. He is not interested in the actual reality of Indigenous people’s presence on Turtle Island, but in the nullification of our bodies, in the murderous death by a thousand omissions. And in his candor, he recalls the thousands upon millions of omissions from a history that has only ever been written by white people who know full well that there were Indigenous peoples in the Americas, but who cannot bear to reckon with the reality of our absence, our genocide.

Thus, it is easier for men like Rick Santorum to simply wave his hand and imagine that we were never even here to begin with. There is no reckoning—or to put it in the Biblical terms, no redemption—if those crimes are never admitted in the first place.

By now, we are all familiar with this white nationalist nostalgia, this yearning for a bygone era of cultural unity and moral rectitude. But what stands out about Santorum’s remarks is not this rote conservatism, but rather a moment of sincerity in which, against his own designs, he reveals the disavowal that is required to sustain this conservative ideology.

Joseph M. Pierce is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and associate professor in the department of Hispanic languages and literature at Stony Brook University.