When Arthur Sackler died in 1987, his obituary in the New York Times noted that he owned one of the largest collections of Asian art in the world. Patrick Radden Keefe’s new book Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty is an exposé of the family whose name has become synonymous with the opioid epidemic in the United States—but it also offers some prehistory about the Sacklers’ relationships with museums.

Arthur is now considered the “good” Sackler, since he died before his family’s company began making OxyContin. Nevertheless, his life—and especially his collecting practices—were not without controversy.

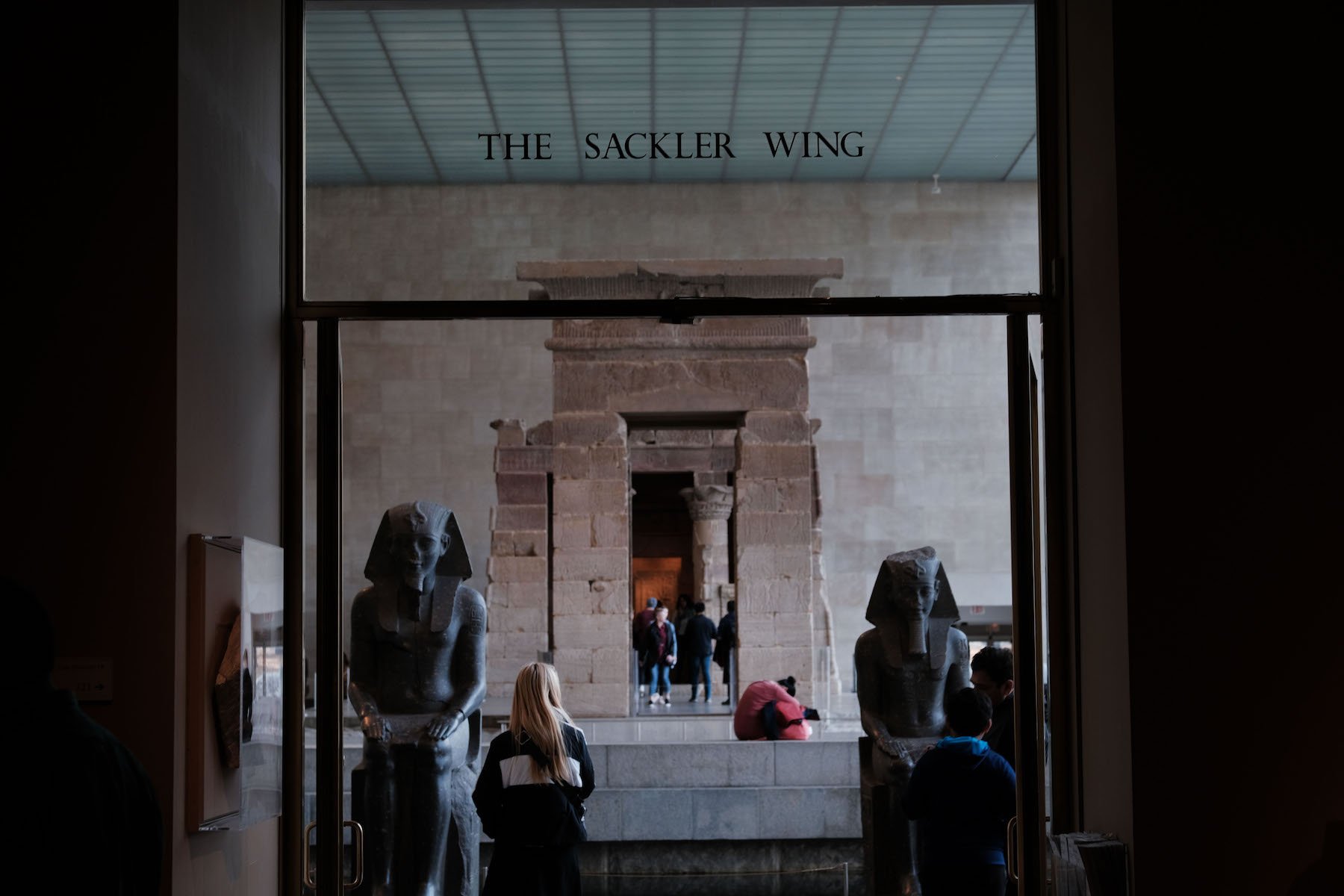

In 1978, ARTnews reported on the existence of the enigmatic Sackler “enclave” within the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, wondering whether it was a “Public boon or private preserve?” That particular bit of coverage was spurred by an investigation by the attorney general, who had caught wind of Sackler’s storeroom in the museum, and set out to determine if it amounted to “an improper use of the museums’ space and resources.”

By then, the unconventional arrangement had already been in place for more than 10 years.

The “enclave” was actually a 600-square-foot gallery-cum-warehouse that Arthur Sackler had commandeered as his personal storage facility, a deal he wrangled by dangling the possibility of eventually gifting the trove to the museum, according to Empire of Pain.

Cover of Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain (2021).

When the handshake deal was made twelve years earlier in 1966, Sackler was just beginning to dabble in philanthropy. He offered his largesse to institutions in exchange for having his name (and that of his brothers, Mortimer and Raymond) emblazoned, mounted, and stamped on institutions around the world.

That year, Sackler made the acquaintance of the then-director of the Met, James Rorimer, a driving force behind the creation of the Cloisters and a member of the US Army’s famed Monuments Men art recovery corps during World War II. At that point, according to Keefe, Sackler’s home in Long Island and apartment in Manhattan were both overflowing with objects the tycoon had acquired during frenzied buying sprees (he once bought 30 bronzes at the Parke-Bernet auction house in a single evening).

Rorimer at this time was fundraising for updates to the Met. Sackler offered to contribute $150,000 toward renovations in exchange for renaming the second-floor the Sackler Gallery—but he “also proposed a more exotic arrangement.”

The arrangement, Keefe writes, was that Arthur Sackler would purchase all of the Asian artworks in that space for the same price the Met had originally acquired them for in the 1920s (a significant amount less than they would have been worth in 1966). Then, Sackler would donate them back to the museum, to be noted as a “Gift of Arthur Sackler.”

This, Keefe writes, was a “classic Arthur Sackler play: innovative, showy, a little bit shady.” It was because of this promised gift that Sackler was able to ask for another, even more absurd perk: having his own storeroom within the museum.

The “enclave” had all of the benefits of being in the museum, with climate control, security guards, and prime New York City real estate, as well as its own number. Sackler had the locks changed so that Met employees could not enter the room, and made a spare key for his friend, the art collector Paul Singer.

“The space was run independent of the museum and in our opinion the museum was in breach of its own practices,” Charles Brody, the assistant deputy attorney who investigated the “enclave,” would tell the Washington Post.

Rorimer signed off on the scheme hoping that Sackler would ultimately gift his entire collection, or at least some of it, to the museum. In Empire of Pain, Arthur’s son-in-law Michael Rich describes the enclave as being “kind of like that last scene in Citizen Kane… it wasn’t a place that celebrated the art. I flashed on Rosebud when I saw it.”

Visitors to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery look at an exhibition on Buddhas in Washington, DC on March 26, 2019. (Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images)

As it happens, Rorimer died later that year. Sackler would go on to have a chilly relationship with succeeding directors of the Met, first Thomas Hoving and then Philippe de Montebello, who presided over the museum in 1978 when officials began looking into the curious arrangement. Ultimately, Sackler and de Montebello’s relationship soured to the point that Sackler opted to donate his collection to the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

“Nobody plans to do anything,” de Montebello told the Washington Post‘s David Remnick at the time, “but obviously the reason it was housed here was so that we would ingratiate ourselves to Dr. Arthur M. Sackler so that he might donate to us all or part of his collection.”

Now, decades later, as photographer and activist Nan Goldin’s P.A.I.N. movement and a slew of lawsuits lay bare the extent of the Sackler family’s part in fueling the opioid crisis, the same institutions around the world are announcing, one after another, the decision to part ways with the Sackler name, promising to remove the traces of the tainted gifts and refuse further philanthropic agreements. The Met’s Sackler Wing has not been renamed.