New York galleries are about to shutter for their holiday breaks, but before they do, can I entice you to take a pause from shopping to visit three superb exhibitions? Each is by an essential Korean artist who remains too little known in the United States. Tremendous pleasures await.

Installation view of “Ha Chong-Hyun: 50 Years of Conjunction” at the Tina Kim Gallery, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Tina Kim Gallery. Photo by Ahn Cheonho

At the Tina Kim Gallery in Chelsea, “Ha Chong-Hyun: 50 Years of Conjunction” is on view through Saturday. Ha, 90 next year, is a grand master of Dansaekhwa, the monochrome painting movement that arose in 1970s South Korea, which was then ruled by a military regime. In the “Conjunction” works being feted here, Ha pushes a single color of paint through the back of raw burlap, then makes marks on the front. They are paragons of restraint, of how much you can conjure from very little, and you might even say that their candor embodies a certain prepossessing ethical stance.

A few examples from the 1980s and ‘90s are variously black, gray, and white, with quick marks: hard-won beauty. In more recent pieces, Ha wields explosive color, sumptuous color in a manner that is joyous, incisive, and potent. Conjunction 23-39 (2023) is as red as red can be, with six thick, meaty marks gliding down its surface. The 7½-foot-wide Conjunction 24-20 (2024) is an almost pointillist constellation of minute brushstrokes—impressions, really—ranging from a deep, watery blue to a fulsome white. It recalls fresh snow falling on ice or light moving through water, a dark place suddenly illuminated.

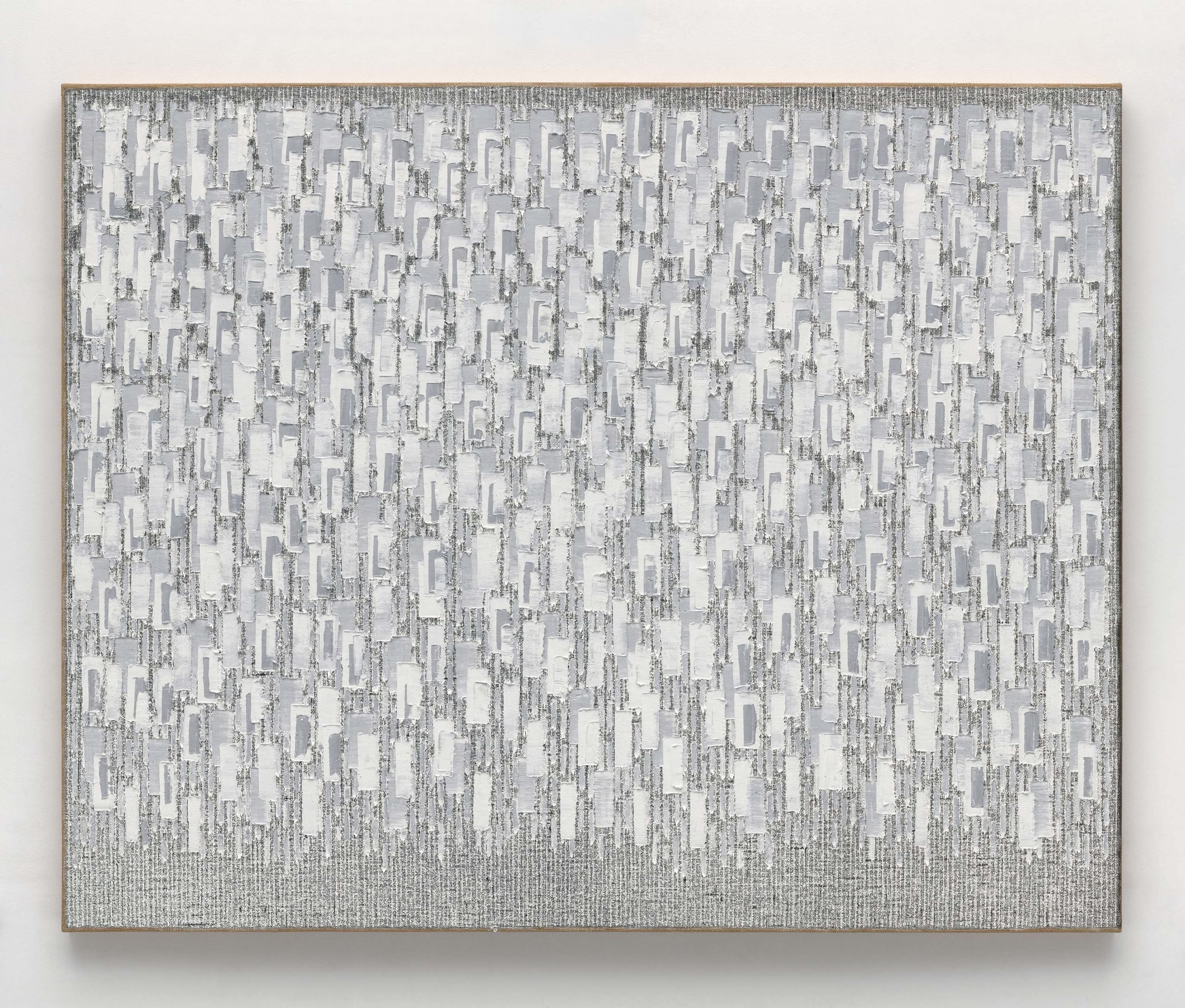

Park Seo-Bo, Ecriture No.221115, 2022. Photo © White Cube, photo by Theo Christelis

You have a little bit more time to catch “Park Seo-Bo: The Newspaper Ecritures, 2022–23,” a moving exhibition that runs at White Cube through January 11. Park, another Dansaekhwa legend, and a longtime friend of Ha, died in October 2023, at the age of 91. In his final years, sick with cancer, he embarked on this astonishingly beautiful series, mounting individual sheets of old newspapers (a 1959 Guardian, a 1964 Le Monde) to canvases, applying patches of white paint, and then running a pencil through them. These are quiet, enigmatic artworks, records of an artist blocking out history as he registers his presence. (Robert Ryman, Hanne Darboven, and Jasper Johns’s crosshatches may come to mind.)

Park was, in a sense, returning to his roots. In the late 1960s, he made his first “Ecriture” abstractions by scribbling repetitively through wet paint on canvas. (The Guggenheim owns a stunning one.) At a glance, these trademark works can recall Cy Twomblys, but their laborious genesis connected, for the artist, to Daoist and Buddhist beliefs about emptiness and meditation. Later, Park incorporated traditional Korean hanji paper, blazing colors, and larger canvases, and he became the most famous artist of his generation at home, as his work took on a certain impersonal, uniform elegance. The White Cube works are, instead, intimate and almost—but not quite—tender. Look at the insistence of Park’s marks, their conviction. He was a force. He remains one.

Installation view of “Hyun-Sook Song” at Sprüth Magers, New York. © Courtesy Sprüth Magers Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Last but not least: Hyun-Sook Song’s solo show at Sprüth Magers, which I regret closes today. Song, 72, was born in Damyang, a rural area outside of Gwangju, and moved in the early 1970s to West Germany to work as a nurse, like many of her fellow countrywomen. She stayed, studying at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Hamburg. Her paintings at Sprüth Magers manage to be at once plainspoken and otherworldly, nearly empty and teeming with life.

Their deadpan titles do not betray their majesty. 7 Brushstrokes over 1 Brushstroke (2023) has, yes, seven wide, shimmering strokes, but they are gradients that span from brilliant white to a dense black-green, and they veil a long, thin bamboo stick. That form recurs in these pictures, poking out from or hiding behind her brushstrokes in a manner that is by turns playful or reticent. Like, say, Giorgio Morandi, Song is able to use the most commonplace objects to plumb the slippery nature of reality. Unexplored realms of metaphysics flow through her pictures, and yet there is absolutely nothing fussy about them. This is Song’s first solo outing in the United States. We need another one soon.