Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, clawing down another art-tech rabbit hole…

MINT CONDITION

In the opening days of April, an artist operating under the pseudonym Monsieur Personne (“Mr. Nobody”) tried to short-circuit the NFT hype machine by unleashing “sleepminting,” a process that complicates, if not corrodes, one of the value propositions underlying non-fungible tokens. His actions raise thorny questions about everything from coding, to copyright law, to consumer harm. Most importantly, though, they indicate that the market for crypto-collectibles may be scaling up faster than the technological foundation can support.

Debuted as part of an ongoing project titled NFTheft, sleepminting serves as a benevolent but alarming crypto-counterfeiting exercise. It aims to show that an artist can be made to unconsciously assert authorship on the Ethereum blockchain just as surely as a sleepwalking disorder can compel someone to waltz out of their bedroom while in a deep doze.

Remember, to “mint” an NFT means to register a particular user as its creator and initial owner. Theoretically, this becomes the first link in a verified, unbreakable chain of custody tethered to an NFT for the life of the underlying blockchain network. Thanks to this perfectly complete, perfectly secure, and eternally checkable data record, the argument goes, potential buyers can trust non-fungible tokens without necessarily having to trust their owners or sellers. These traits add a valuable layer of security that traditional artworks could never rival with their eternally dubious off-chain certificates of authenticity and provenance documents.

Personne may have found a way to dynamite this argument for much of the art NFT market. Sleepminting enables him to mint NFTs for, and to, the crypto wallets of other artists, then transfer ownership back to himself without their consent or knowing participation. Nevertheless, each of these transactions appears as legitimate on the blockchain record as if the unwitting artist had initiated them on their own, opening up the prospect of sophisticated fraud on a mass scale.

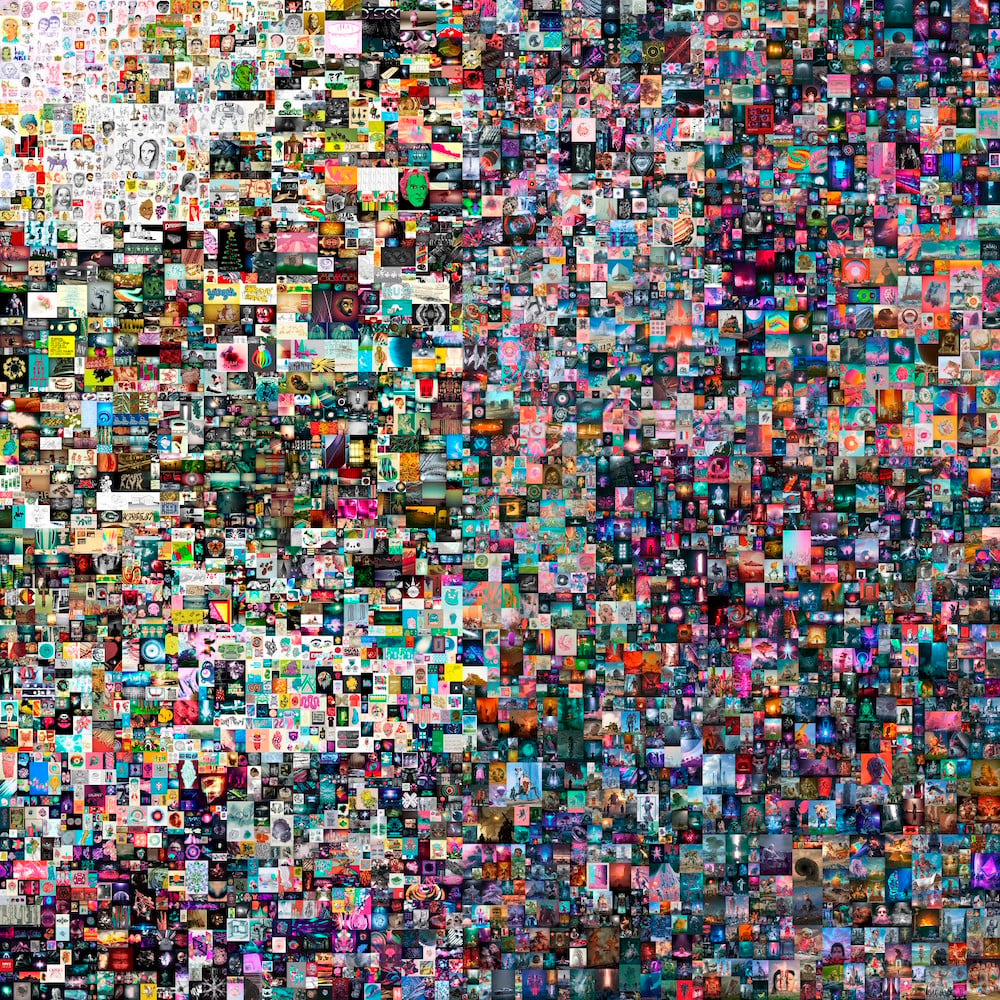

To prove his point, on April 4, Personne sleepminted a supposed “second edition” of Beeple’s record-smashing Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, the digital work and accompanying token that sold for a vertigo-inducing $69.3 million via Christie’s less than a month earlier. (My emails to Beeple and his publicist about the situation went unanswered.)

In our ensuing email exchange, Personne claimed he then gifted the sleepminted Beeple (Token ID 40914, for the real crypto-heads) to a user with the suspiciously appropriate handle Arsène Lupin, an homage to the famous “gentleman thief” created by Maurice Leblanc and recently reincarnated in a hit Netflix show. (Personne denied he was Lupin to the blog Nifty News.) Lupin then turned around and offered the sleepminted Beeple for sale on Rarible and Opensea, two of the largest NFT marketplaces—both of which eventually deactivated the listings. (Neither Rarible nor Opensea replied to my emails seeking comment.)

Why publicize any of this, you ask? Personne essentially sees himself as a so-called white hat hacker, meaning an ethics-driven coder who exploits technological flaws strictly to demonstrate how they can be fixed. He is a staunch believer in the potential of NFTs and crypto. However, he believes major “security issues and vulnerabilities” in smart contracts have been glossed over to make way for the gold rush. He also claimed to have launched the NFTheft project only after the crypto-community largely ignored or derided his attempts to spark earnest conversation.

“The goal I want to achieve with this is to take the most expensive and historic NFT, and show that if it is not protected, how can we guarantee that any NFT is safe from intentional malice, fraud, forgeries, theft, etc.?” he wrote.

Although the sleepminting saga is hairier than a Haight-Ashbury commune, I think we can chop through the overgrowth using two questions with serious stakes for different participants in the NFT market.

Screen grab of the NFTheft website showing details of the “sleepminted” token.

1. What does sleepminting tell us about the technological vulnerabilities of art-related NFTs?

Short Answer

The main smart contract driving the market might not be smart enough to secure the frenzied level of buying and selling we’ve seen in 2021.

Longer Answer

What’s clear is that Personne is exploiting a flaw in the standard ERC721 smart contract, which is used by the overwhelming majority of art-related NFTs transacting on the Ethereum blockchain. But it is not an easy-to-see flaw, and the effect is not being faked by Photoshop wizardry or some other non-crypto chicanery; the sleepminted Beeple really is minted in Beeple’s wallet, it really is transferred elsewhere afterward—and both of those transactions are memorialized forever on the blockchain.

How, exactly, is Personne doing this at the level of code? He declined to elaborate, saying only that he would publicly reveal the details before initiating the next stage of the NFTheft project. Other crypto-fluent folks I talked to needed more time to investigate than my deadline would allow. But Personne revealed in one tweet that he had deployed a “custom-built” contract that did not have an unnamed ERC721 “security check in place,” allowing him to move the token from wallet to wallet without meeting the typical conditions (for instance, a buyer sending funds to meet a set sales price).

Good luck identifying the flaw, though. Kevin McCoy, the creator of the first NFT, tried running Personne’s sleepminting smart contract through a decompiler to get more insight into the source code. His highly technical, highly candid snap take on the results was that they were “fucking crazy” with “all kinds of shit going on,” but he could not decipher the actual function responsible for the mischief.

A courtroom sketch of Domenico De Sole on the witness stand with the fake Rothko painting he bought from Knoedler gallery. Photo: Elizabeth Williams, courtesy Illustrated Courtroom.

Why It Matters

Sleepminting is likely more sophisticated than the average NFT buyer’s understanding of the technology, making those buyers unlikely to question what appears to be blockchain-verified authorship.

This is especially important because we’re in a market frenzy for NFTs right now. Thorough vetting falls by the wayside whenever under-informed buyers flood into a largely unregulated space. Fraudsters have made millions in the past selling fake Jackson Pollocks on eBay, and the Knoedler forgery scandal proved that even knowledgeable collectors can be susceptible to high-level chicanery.

I can’t rule out that a savvy crypto-collector might be able to detect a giveaway in either a sleepminting contract or its data trail. It’s also true that, even without Personne publicizing what he’d done, market players could use off-chain research to find out whether Beeple actually minted a second edition of Everydays—just as, say, Warhol collectors could consult the catalogue raisonné to make sure a particular Marilyn canvas is regarded as authentic.

Still, if bad actors began exploiting vulnerabilities in ERC721 contracts, it could theoretically plunge the NFT market into a forgery crisis on par with the antiquities market, where recent research showed that up to 80 percent of what is offered online is likely either looted or fake.

Incidentally, Personne alleges that 80 percent of the NFTs on the market are “invalid and need to be redone” because of their vulnerability to sleepminting. That’s a difficult estimate to corroborate. But even if he’s overshooting by two or three times, the financial exposure would swell to millions of dollars in art-related NFTs alone. Isn’t that a prospect worth investigating?

A courtroom setup awaiting a witness. Photo: Friso Gentsch/dpa (Photo by Friso Gentsch/picture alliance via Getty Images)

2. Does sleepminting violate any U.S. laws?

Short Answer

The legal exposures are murky and hard to act on, but they exist. In a way, that’s the point.

Longer Answer

At present, NFTs still occupy a legal gray zone. As of my writing, multiple cases pending in the U.S. could influence their ultimate classification. What’s unclear is how much immunity a sleepminter would have based on the lingering ambiguity.

Personne told me that, after being “thoroughly consulted and advised by personal lawyers and specialist law firms,” he is confident there are “little to no legal repercussions for sleepminting.” His argument is that ERC721 smart contracts only contain a link pointing to a JSON (Javascript Object Notation) file, which in turn points to a “publicly available and hosted digital asset file”—here, Beeple’s Everydays image. (Remember, the NFT is almost never the artwork itself.)

He likened the idea of suing him to the “absurd” prospect of Apple suing “every single pedestrian for viewing or photographing their billboard in Times Square.”

But multiple prominent art attorneys I spoke to felt Personne is standing on shakier legal ground. “If the hacker is not trying to pass the sleepminted work off as authentic and charging money for it, then he is probably not in any danger of being charged with criminal fraud,” said Steven Schindler, a founding partner at Schindler Cohen and Hochman. “If he were to be misrepresenting the nature of the NFT, and selling the works under false pretenses, then he would certainly be open to charges of fraud.”

But fraud isn’t the only issue at play here. Let’s return to Personne’s contention that the token merely points to a publicly viewable digital file. Querying the blockchain seems to show that the original Everydays NFT and Personne’s sleepminted “second edition” have two different URIs—essentially, the alphanumeric code identifying the actual image file that the token grants ownership to. This implies he downloaded the original file and re-uploaded it to a different online location.

Further, it looks like he did so without making any changes to the work that could be positioned as “transformative,” like, say, Richard Prince cropping out the Marlboro ad copy in his “Cowboys” photographs, or adding nonsensical comments to other people’s Instagram selfies in his “New Portraits” series. (Two copyright infringement cases on the latter are currently pending in the Southern District of New York.)

Richard Prince. Photo: Patrick McMullan

So even though the sleepminted token is not the artwork, it still needs to point to the artwork in order to mean anything. If Personne made this happen by reuploading an unaltered digital copy of Beeple’s Everydays, as the URI suggests, then that could very well still qualify as unauthorized reproduction of an artwork whose copyright Beeple still owns.

In short, it’s possible a court could find him liable to be “in violation of Beeple’s exclusive right to publicly display his work,” according to Megan Noh, co-chair of art law at Pryor Cashman.

Personne may also be running afoul of what’s known as the Lanham Act, specifically a clause known as “false designation of origin.” Remember, the entire point of sleepminting is that its unauthorized attribution to Beeple appears legitimate on the blockchain. These claims are reasserted in the details of the sleepminted token on the NFTheft website (“Creator: Beeple (b. 1981)”) as well as the listings on Rarible and Opensea.

“The ‘statements’ on the website and/or created by the intentionally-manipulated metadata feel a lot like ‘false designations of origin,’ which could give rise to liability,” Noh said. “But there’s also an interesting question about whether an NFT can be considered a ‘good or service,’ which it would need to be for this area of the law to apply.”

Screen grab of the Rarible listing for the sleepminted token, showing the current owner as Arsene Lupin and the creator as Beeple.

Why It Matters

Personne’s copious public proclamations that the sleepminted NFT was not, in fact, authorized by Beeple may not protect him in a U.S. court—precisely because he engineered the blockchain to say otherwise. If a sleepminted token truly made it out “in the wild,” as Personne told me it did, then his exposure could only increase as the token moved through the secondary market to buyers who may be less aware of the NFTheft site, his social media presence, and any other links back to his white-hat rhetoric.

That said, anyone who wanted to sue Personne would likely first have to untangle his identity, since it’s not easy to bring a pseudonymous party to court. Again, good luck.

Incidentally, this is one of the reasons it still seems unlikely to me that Lupin, the pseudonymous owner of the sleepminted NFT, is anyone other than the same person behind… uh, Personne. The best way to protect yourself from misunderstandings by subsequent owners is to ensure there are never actually any subsequent owners.

Debating the legality of this particular episode misses the larger point, though.

The NFTheft project aims to show that a gigantic proportion of the art NFT market is vulnerable to such malicious intent because of a structural flaw in the standard smart contract. If Personne were a bad actor, he could have sleepminted a much less famous NFT, kept quiet about his custom smart contract, and started selling directly to the most naive buyers he could find. That real people could be tricked into losing real money, and that anyone undertaking the ruse could plausibly be found liable for damages, reinforce why Personne’s gambit is worth our attention.

We have already seen sophisticated hacks siphon tens, even hundreds, of millions of dollars out of cryptocurrency exchanges, decentralized financial entities, and blockchain-based “smart” organizations. Maybe it was only a matter of time before someone figured out a way to do the same to the part of the NFT marketplace that relies on ERC721 contracts. The question is whether the biggest and most influential players will take action before the black hats dig in.

[NFTheft]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember what Upton Sinclar said: It is difficult to get someone to understand something when their salary depends on them not understanding it.