Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, asking when enough is enough…

ONCE IN A LIFETIME

Last Wednesday, Kevin Roose of the New York Times detailed the emergence of what he called the “YOLO economy,” as scores of young professionals bust previously unfathomable career U-turns sparked by the realization that “you only live once.” Despite art’s perceived status as one of the ultimate passion-above-all pursuits, however, I’m skeptical that our niche industry will see a huge amount of new participation from this shift in the zeitgeist. Instead, I’m inclined to believe that the epochal upheaval of the past year is less likely to produce a slew of daredevil ventures than a smaller, more consolidated art world that actually prioritizes playing it safe.

Roose’s argument primarily focuses on upwardly mobile professionals in their late 20s and early 30s who have grown to distrust the “traditional white-collar career path” during the unforeseeable chaos of 2020 and early 2021. He sums up the dissonance this group has been experiencing by writing:

They had watched their independent-minded peers getting rich by joining start-ups or gambling on cryptocurrencies. Meanwhile, their bosses were drowning them in mundane work, or trying to automate their jobs, and were generally failing to support them during one of the hardest years of their lives.

This system shock is now sparking a variety of strong reactions from non-essential workers across industries, according to Roose. His interviewees include a high-powered attorney who bailed on “a partner position and a big-firm salary to take a job at a small firm run by his next-door neighbor”; a Daily Beast reporter who ditched the hypercompetitive New York media sphere for a new life of freelance writing, kayaking, and recreational painting near her parents in Florida; and a buyer at a “major clothing retailer” about to walk away from a low six-figure salary for a next chapter still to be determined.

(The pursuits under consideration by the soon-to-be-ex-buyer include learning to code, mining Ethereum, working on an upcoming political campaign, opening a tourism business in the Caribbean, and launching a line of artisanal maple syrup. I only fabricated one of those options.)

Roose argues a host of different factors are making these dramatic course-corrections feel newly viable to the last of the millennials and the first of the zoomers. High earners with in-demand skills feel emboldened by a year of huge returns on Wall Street, low interest rates, and a glut of openings in “remote-friendly industries” like tech and finance. Other workers may have at least slightly more cushion (or less debt) thanks to multiple rounds of stimulus payments and more generous unemployment benefits. Online day trading and the NFT slot machine have also delivered silly amounts of cash to savvy (or just straight-up lucky) market players across income bands.

Yet closely analyzing the “YOLO economy” reveals that the phenomenon encompasses more than just privileged young professionals luxuriating in enviable options. No matter their tax bracket or employment history, workers seem to be asking themselves whether the benefits of their chosen careers are worth the cost to the rest of their lives—a fundamental question made newly visceral by reckoning with mass uncertainty, loss, and death on a daily basis since March 2020.

Plenty of people seem to be wrestling with the same dilemma in the art industry, too. Across sectors, and even across age groups, more and more of them appear to be reaching the conclusion that the pain has become too extreme for the possible gain of continuing on in a field that looks more and more like scorched earth.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Photo by Liao Pan/China News Service via Getty Images)

NONPROFIT NONSTARTERS

Earlier this month, the American Alliance of Museums published a study quantifying the shutdown’s effects on the nation’s past, present, and future institutional staffers. The data came from 2,666 respondents predominantly composed of paid museum employees. Their answers suggest U.S. museum labor is being hollowed out less by the recognition that you only live once than by the prospect that the industry is continuously draining the life force from its workforce.

Among paid museum staff and students (who together made up 90 percent of the sample), more than one-fifth rated it “unlikely they will be working in the sector in three years.” Less than half (46 percent) considered it “very likely” they would persist in the field that long. Although students made up just a thin sliver of the overall sample (three percent), their expectations were especially grim; a staggering 92 percent anticipated there would simply be no museum jobs for them by 2024.

What are the main barriers to a long-term career in U.S. institutions? Fifty-nine percent of qualifying respondents doubted they would earn sufficient compensation; 57 percent flagged burnout; and 53 percent cited discouraging prospects for advancement. Slightly more than one-third of the sample even invoked disillusionment with the value of museum work as a whole—surely a read sharpened by a year in which the stakes outside the institution felt higher and more urgent than ever.

These bracing numbers come with caveats of course. As my colleague Sarah Cascone noted, it’s plausible that the AAM’s survey reached only a fraction of the U.S. museum workers furloughed or laid off during the public health crisis, especially since the majority of cuts landed on frontline staff more likely to leave the industry entirely. It seems plausible that the gloom could have been even heavier with big input from these groups.

Ethnicity and gender data complicates the picture. BIPOC respondents, who “were more likely to have been under financial stress at some point over the last year,” represented only 20 percent of the overall sample, versus roughly 42 percent of the national population per U.S. census data. (Museums largely remain slow to address the discrepancy.)

While that imbalance could be skewing the report in an undeservedly favorable direction, its gender data could be doing the opposite. Women made up 79 percent of respondents and proved significantly more likely than men to report increases in their workload and hours, decreases (or total losses) in their salary and benefits, and less optimism about the future as a result of the shutdown.

In the end, the AAM decided these acknowledged imperfections in methodology gave no reason to hold back an aggressive conclusion, calling the impact on museum workers “clear, severe, and troubling.” If that verdict doesn’t suggest many of them may be considering spending their one and only life in another profession, regardless of their age and income situation, I don’t know what would.

Rashid Johnson, Untitled Escape Collage (2019). © the artist. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles and Sammlung Goetz, Munich. Photo: Martin Parsekian

ESCAPE ARTISTS

U.S. museum staff aren’t alone in second-guessing the sacrifices of the current art ecosystem. The shutdown has been slamming non-superstar artists into the wall, too, and many are wondering if it’s still worth it to try to break through.

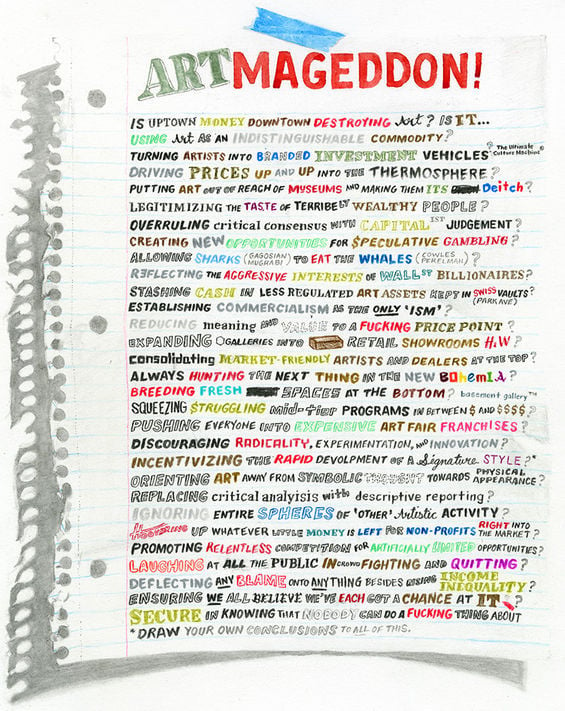

No one I’ve talked to or read about recently summed up the prevailing feeling better than the respected Brooklyn artist and activist William Powhida. When I asked him how many artists he knew were responding to the past year by taking bigger creative or professional risks, he suggested the premise should be inverted. “I think, as a category, most artists made this ‘YOLO’ decision a long time ago and are re-thinking that in the opposite direction,” he said. The only possible exceptions he could conjure were NFT artists potentially surfing out of their galleries on a wave of speculative cash.

To be clear, my sense is that U.S. artists are not (yet) racing for the exits en masse. But larger economic conditions do seem to have them examining the issue with newly critical eyes. Unlike the 2008 financial crash or 9/11, our current crisis has triggered a cascade of democratically socialist programs that have only heightened an awareness of the grander costs of a studio practice in “normal” times, especially for artists based in expensive hubs like New York and Los Angeles.

The message I’m hearing is that once your load has been lightened by enhanced unemployment payments, eviction freezes, and forgivable small business loans, it’s hard to un-see the size of the burden you were carrying to maintain a studio practice before—and are likely have to shoulder again soon, barring a paradigm shift in American politics.

It’s also important to recognize that, just like building a career as a museum professional, building a career as an artist tends to foist even more challenges onto BIPOC and women.

For example, in an April 2019 piece on the particular burnout experienced by many Black artists, Melissa Smith reported that interdisciplinary artist Steffani Jemison “frequently writes her own press releases because white curators are too afraid to do this themselves” and often feels pressured to act as a “spokesperson for Blackness in general” when showing in exhibitions devoid of other Black artists. These are not the types of added responsibilities, say, Chase from Greenwich, Connecticut would have to take on if he emerged from Yale’s MFA program with curators and collectors slobbering after his every new work.

Steffani Jemison, REVELATiON (2017). Photo by David Dashiell, courtesy of MASS MoCA.

Meanwhile, a joint study by Artnet News and In Other Words found that women artists made up only two percent of fine-art auction sales and 11 percent of acquisitions by U.S. art museums between 2008 and mid-2019. A very real level of artistic success can be enjoyed outside those data points, of course, but they nonetheless suggest that everything from disproportionate child-care demands and a paucity of paid family leave, to structural sexism in the pay scale deals women artists an even worse hand than their male counterparts.

And keep in mind, this was the case before a slow-motion cataclysm that left people inside and outside the art world claiming their affiliation with one of three life-saving vaccine-makers with the same casual pride they announce their astrological sign. The upheaval we’ve experienced since then has only given current and aspiring artists’ more reason to think about whether a career in the studio is worth the existential costs.

Even some renowned dealers are choosing to opt out in pursuit of holistic fulfillment. In an interview with my colleague Eileen Kinsella, Metro Pictures cofounder Janelle Reiring invoked the “YOLO” mantra almost word for word in explaining the rationale for sunsetting the storied gallery. After clarifying she and cofounder Helene Winer “in no way” decided to close because of the ongoing crisis, Reiring said:

It’s totally a personal decision. Exterior factors entered into it, of course. But it’s like, what do you want to do with the rest of your life? Which won’t be that long.

None of this is to say that this unprecedented economy and its tragic underpinnings won’t spawn a brigade of rebellious innovators willing to risk it all for art; every grand disruption does. Museum workers and activists are also pushing hard to make employment in the sector more sustainable through a renaissance of unionization and mutual aid. Even some municipal governments are piloting progressive measures to buoy the cultural sector, including universal basic income programs for artists. Surely some of these will enrich the for-profit and nonprofit sides of the art industry.

Still, I worry that these maverick elements will be too few and far between to vault the trade into the new golden age we’d like to see. So many artists, dealers, and art professionals have already endured so much pain to survive this long. A privileged minority of them may opt out to unwind in the opulent possibilities of the good life. But it shouldn’t surprise us if many others without such a protective halo soon decide to simply get out alive while they still can—and if they do, the cultural landscape will be worse for it.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Sometimes you can’t break away until the only other option is to break down.