The New School has an impressive art collection, defined by its focus on social-justice themes and a number of permanent, site-specific commissions by celebrated contemporary artists including Agnes Denes, Glenn Ligon, and Kara Walker. The crown jewel of this collection is arguably the very first commission to grace the campus: a room containing five frescoes by José Clemente Orozco, completed by the artist in 1931.

The New School’s Orozco room embodies the leftist social themes that defined his output and positioned him within the “big three” Mexican muralists alongside Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros: universal brotherhood, revolutionary struggle, and the dignity and power of workers. One panel titled Science, Labor, and Art seems to foreshadow the changing shape of the university itself, from its founding as a free, progressive school of economics in 1919 to its century-long evolution into a conglomerate of colleges in the arts and social sciences.

The mural’s central figure, a manual laborer wielding a hammer, is bookended by two other figures shown with paper and drafting tools, with a rainbow also in the hand of the artist on the right. Each type of production is shown as important and interdependent, but the composition sends a clear message: Do not lose focus on labor.

Sadly, today the fate of Orozco’s commission seems like a symbol of the New School’s estrangement from its origin story, despite its eagerness to continue branding itself as a progressive institution that takes pride in fostering “an equitable, inclusive, and socially just environment.” Though the murals were designed for a dining hall and student lounge, various renovations to the building over the years and concerns over preservation essentially tucked the Orozco room away into the school’s archives; it is now a rarely used meeting space that most students and faculty never set foot in (though it is possible to view the work by special request).

The irony of this situation was not lost on Nomaris Garcia Rivera, a recent Parsons graduate who wrote an essay about the Orozco room for the New School Free Press in 2020, her junior year. Rivera argued for restoring public access to the work, concluding that “living and engaging with the art is the ultimate purpose of a mural. I believe that Orozco would argue that it is the ultimate purpose of all art.”

Rivera’s critique symbolizes how the New School’s community must grapple with the dissonance between its activist legacy and its current reality. Woke branding and a nonbinary narwhal mascot can’t disguise the corporate model the university’s administration has long embraced, leading one student to recently comment on Instagram that it is a “shell of faux progressive ideals.”

Faculty who teach part-time at the New School belong to a class of contingent instructors commonly labeled as “adjuncts” elsewhere. But the New School avoids this term, perhaps to nominally acknowledge that we are anything but inessential to the school’s functioning—so-called “Part-Time Faculty” make up 87 percent of the New School’s teaching staff.

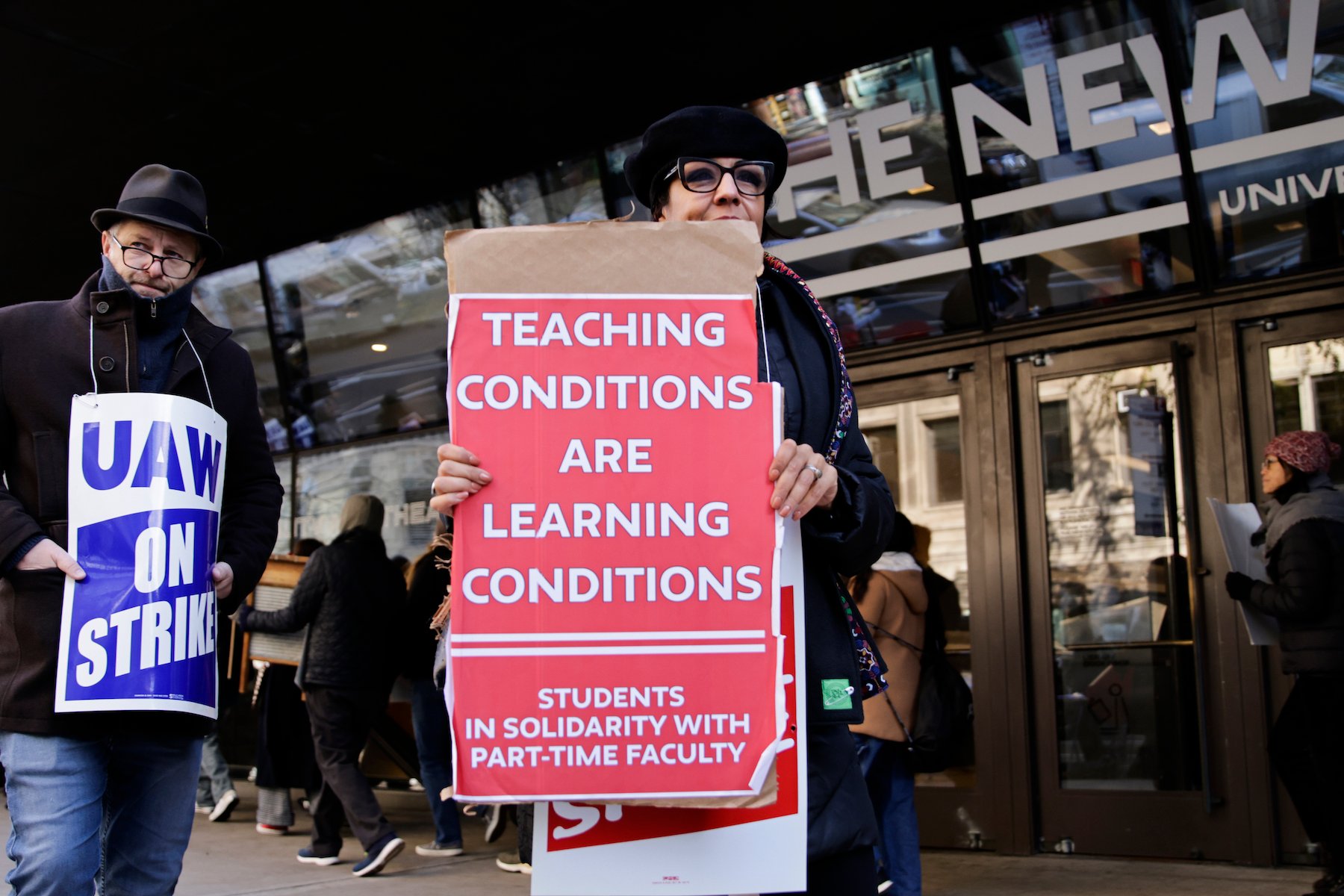

A picket line in front of the Parsons School of Design in Greenwich Village on November 17, 2022 in New York. (Photo by Kena Betancur/VIEWpress)

After fighting against the unionization of its part-time faculty back in 2005, the New School’s administration recommitted this fall to their aggressive, anti-labor tactics in negotiations with the people who are the true lifeblood of the university, opting to hire a lawyer from Akerman LLP, a firm that boasts about its record suppressing union organizing. The university has staunchly refused to grant our union a fair pay raise that is long overdue. Meanwhile, data shows that the New School spends over twice the national average on administration relative to their spending on instruction. Top executive salaries exceed half a million dollars annually.

Most of the university’s part-time faculty are at Parsons School of Design, the largest entity under the New School umbrella since the two institutions affiliated in 1970. Parsons’s reputation as a leader in arts education dates back to the era before this merger, when it was the first school to offer programs in design. You’ll find plenty of luminaries among its alumni, from mid-century icons (Jasper Johns, Alexander Calder) to New York-based artists defining the field today (Sable Elyse Smith, Mary Mattingly).

Similarly, a list of alumni and faculty in the School of Fashion is a who’s who of both the local and global scene. This is possibly why one of the school’s most successful fundraising campaigns is its fashion-focused—and often celeb-studded—“Parsons Benefit” gala.

Despite the school’s prestige, the university says it cannot afford to pay its faculty above poverty wages. In 2022, the starting rate for a semester-long studio course was a mere $4,300 at Parsons, which is the same rate paid since 2018. Faculty teaching five of these classes per year would make $21,500—less than the median annual rent of a one-bedroom apartment in New York City.

At the time of this writing, the university’s best offer for raising compensation in the next year has been an increase of 3.5 percent—but accounting for the rate of inflation, the real dollar value of this proposal would actually pay less than we made four years ago. Simply matching that amount today would require an increase of at least 18 percent.

The situation is emblematic of not only the New School’s broader identity crisis, but also the institutionally normalized inequity endemic to New York’s culture industry and higher education all across the U.S. Part-time faculty at Parsons, teaching in one of the wealthiest cities on the planet, must accept that the comforts and benefits customary of most white-collar jobs are unattainable luxuries for us—even after many years of hard work for the school.

Perhaps it is easier to make rent on a Parsons salary with a supportive partner’s income in the equation. Yet if one wants to have children, there are no options for paid parental leave. I’ve heard about this from several colleagues. One was lucky that her baby was due during winter break, allowing an entire month off from teaching; another miraculously found a way to return to the classroom within a couple weeks of giving birth. Such conditions would be inhumane anywhere, but at an institution that loudly extols “equity” and “inclusivity,” it feels like a form of gaslighting. Over time, faculty’s individual experiences of being mistreated and unappreciated have curdled into a climate of pervasive mistrust.

Like other employers in the culture industry, the New School justifies this unfair system by promoting a convenient myth about the city’s creative workers and their desire for the freedom of the freelance “hustle.” It’s time we unequivocally rejected this romanticization: low pay and a lack of job security does not fuel creative freedom. It fuels stress and anxiety, and ultimately leads to the quiet exclusion of many from academia, creative careers, and often the city itself.

A picket line in front of the Parsons School of Design in Greenwich Village on November 17, 2022 in New York. (Photo by Kena Betancur/VIEWpress)

Though women, gender-nonconforming and trans people, people of color, disabled people, and other historically marginalized groups are still underrepresented in both the arts and academia, our presence has grown enormously in the last fifty years—but better representation will be a hollow victory if it occurs alongside the devaluation of teaching as a profession.

The reality is that institutions like the New School have grown accustomed to running their university as if it were a corporation. They see their students as customers and their faculty as gig workers, asking how they can deliver the product of education at the lowest possible cost. While they won’t willingly reform themselves out of this bottom-line mindset, they may eventually come to realize that no amount of marketing or executive innovation will ever replace simply investing in the people who actually teach the classes.

The university initially stalled bargaining for months, and once they did come to the table their offers have remained far from fair or compromising, leaving the union with no other option but to prepare for a strike when our contract expired Sunday at midnight.

Wednesday morning, our first time rallying together at the picket line, was beautiful. It was especially moving to see some of my own students who are freshly in their first semester at college arrive with handmade signs eager to support us. Fifth Avenue, with its high volume of traffic, turns out to be an ideal place to picket. Among the many drivers who honked in solidarity, I counted MTA bus operators, tour bus operators, local delivery drivers, postal workers, cab drivers, and at least one ambulance. New York is a union town.

A picket line in front of the Parsons School of Design in Greenwich Village on November 17, 2022 in New York. (Photo by Jill Enfield)

Several part-time faculty who have taught for over a decade have described the past weeks as one of the most uplifting experiences of community they have ever witnessed in their many years at the New School. Organized and on strike, we have gained power to reshape the school as a space of real collective care, rather than a tightly controlled collection of assets.

Thinking back now to that famous art collection: If the university covers its walls with the work of political artists while scornfully rejecting the same spirit at the core of how it operates, it risks becoming a museum to progressive ideals rather than a living embodiment of them. If the New School and its legacy are to survive into the future, it must first return to sincerely upholding the values that brought it into being in the first place. That means coming to the table to treat their faculty—and by extension their students—fairly, and prove that they finally understand what we know to be true: we are the New School.