A controversial sculpture of Thomas Jefferson is moving from the New York City Council Chamber to a new home at the New-York Historical Society.

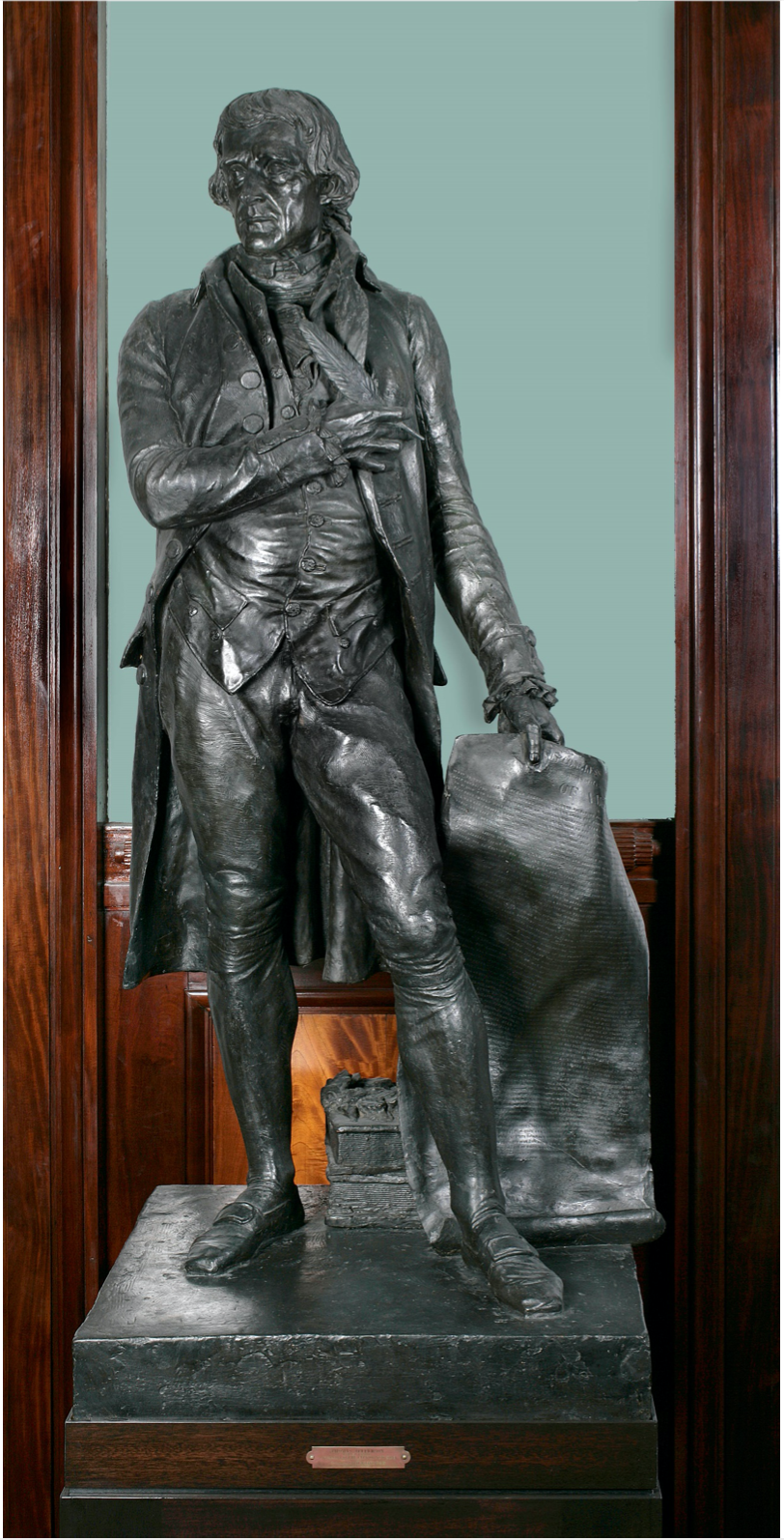

The seven-foot statue by French artist Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, which dates to 1833, is a plaster model of the bronze version at the U.S. capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C. But in recent decades, Jefferson’s legacy as a founding father and the author of the Declaration of Independence has been complicated by the fact that he also owned hundreds of enslaved people, and even fathered children with one of them, Sally Hemings. Along with monuments to Confederate leaders, public artworks featuring the nation’s third president have faced a reckoning in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

The Public Design Commission finalized the relocation of the statue at City Hall on Monday, reports the New York Times. The final decision had been delayed in part due to concerns that the loan would mean New Yorkers would now have to pay to see the piece.

Under the final terms of the deal, the city is loaning the work to the museum for 10 years, starting in April. It will spend six months in the museum’s lobby gallery before moving to the reading room, also on the ground floor. Both spaces do not require museum admission to visit.

The restored New York City Council Chamber in 2012, with the Thomas Jefferson statue on the left. Photo by Glenn Castellano, courtesy of the New York City Public Design Commission.

“The statue will be given appropriate historical context, including details of Thomas Jefferson’s complicated legacy—his contributions as a founder and draftsman of the Declaration of Independence and the contradiction between his vision of human equality and his ownership of enslaved people—and the statue’s original purpose as a tribute to Jefferson’s staunch defense of freedom of religion and separation of church and state,” the museum said in a statement.

Assemblyman Charles Barron began calls for the artwork’s removal in 2001, when he was a city council member. (He believes the statue should be destroyed outright.) But the idea did not gain traction until the council’s Black, Latino, and Asian Caucus took up the cause this year, writing to Mayor Bill De Blasio to call the artwork “a constant reminder of the injustices that have plagued communities of color since the inception of our country.” Its relocation was approved in October.

In 2018, New York’s mayoral advisory commission on city art, monuments, and markers opted not to take down controversial monuments to figures including Christopher Columbus and Teddy Roosevelt, but instead to add additional context to such works. (A statue of gynecologist J. Marion Sims, who experimented on enslaved Black women, was moved to a less prominent location and will be replaced by a tribute to his victims.) But the tide has continued to turn, and a Roosevelt monument at the American Museum of Natural History is now slated for removal.

Pierre-Jean David d’Angers’s bronze Thomas Jefferson sculpture (1833) seen in Lafayette Park in Washingon, D.C., in 1870. The work has since been moved to the U.S. Capitol building. Photo courtesy of the White House Collection.

As for the the Jefferson artwork, it was commissioned by Uriah P. Levy as a gift for Congress. He donated the plaster model to New York City in 1834. (The first Jewish commodore in the U.S. Navy, he saw the work as a tribute to Jefferson’s support of religious freedom in the military.) Before it went on view atop it nearly five-foot pedestal at City Hall that year, Levy charged admission to see it at 355 Broadway, using the proceeds to buy 1,200 loaves of bread for the poor. It has been in the City Council chamber for over 100 years.

A counter proposal from 17 historians had suggested returning the work to the governor’s room in City Hall, where it spent most of the 19th century. The design commission rejected the idea because the room is only open to the public during scheduled tours, and because the city wouldn’t be able to provide adequate context for the work.

The statue was last restored in 2011, as part of a year-long conservation and redecoration of the chamber, which had been suffering from water damage. Its relocation could pave the way for similar campaigns against some of the other 700 works of art at city-owned property.