For the past week, the country has been in a blackout. People are going without food. The director of a major artist’s foundation builds shields from cardboard and carpets to protect protesters from the police’s plastic bullets while canvases by Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon, and Antoni Tàpies hang in dark, hot museums.

And Venezuelans are left to wonder: how long will the turmoil last?

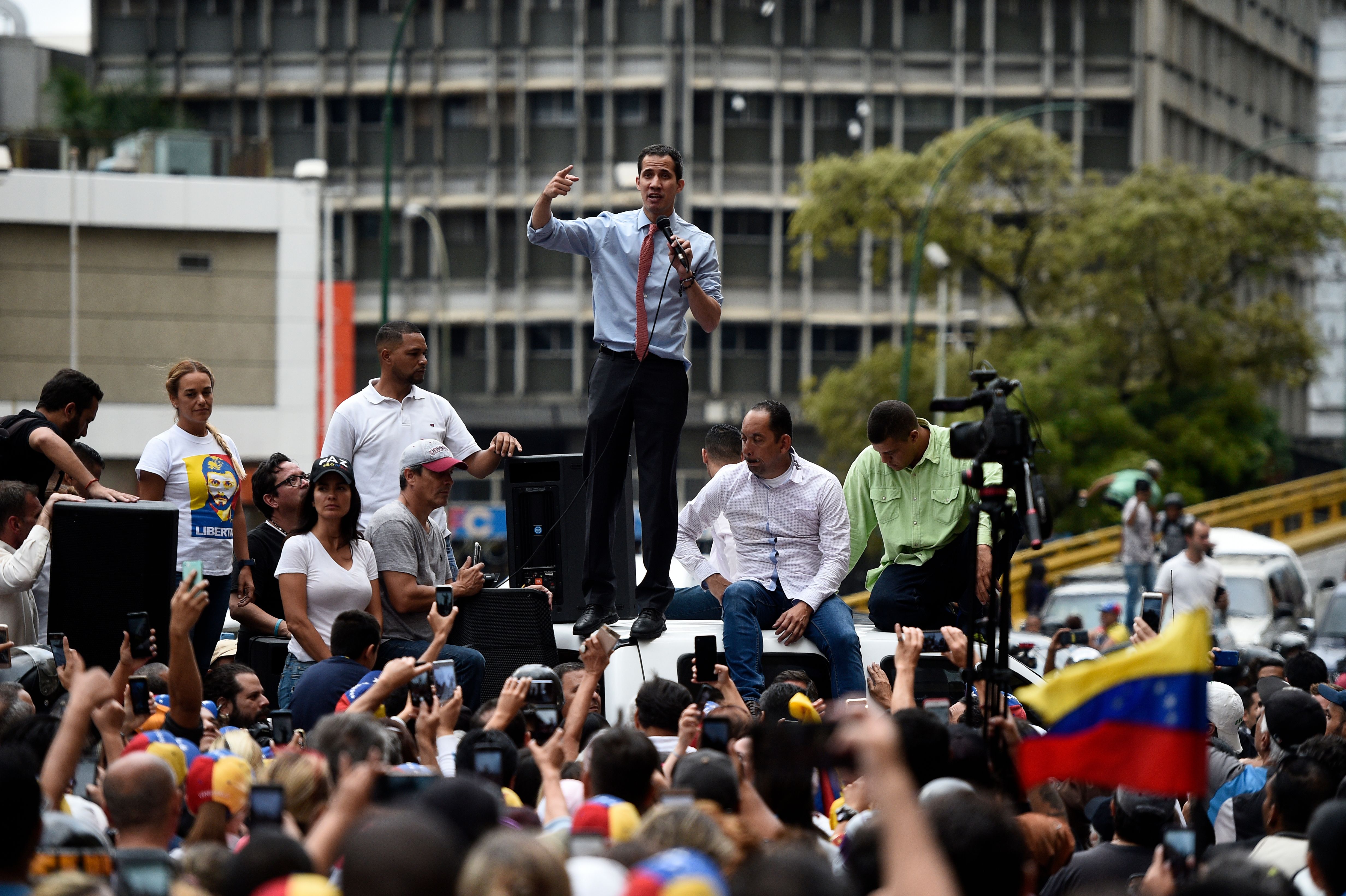

The US, Germany, France and Britain have branded the January reelection of Nicolás Maduro, the oil-rich nation’s authoritarian president since 2013, a sham. His young challenger, Juan Guaidó, is recognized as the legitimate head of state by 50 nations, including the US, while Russia and China are among those supporting Maduro.

But the recent unrest is just the latest in two decades of crisis since Hugo Chávez took power in 1999 and crashed the country’s economy, with profound implications for the nation’s arts community. The country’s history since his ascension is a litany of catastrophic ills: deadly riots, coup attempts, food shortages, galloping health crises, widespread poverty, and hyperinflation, at one point reaching 1.4 million percent. In the largest mass migration in the Americas, three to four million people—approximately ten percent of the population—have fled since Chavez took power.

Juan Jose Olavarria’s The Line (2018) depicts people waiting in line for essentials such as food. Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria, New York.

Artists Hit the Streets

Arts professionals have participated in daily demonstrations, creating anti-Maduro banners and posters, says Alejandra Mendez, director of GBG Arts, a Caracas-based gallery that recently expanded into Miami. Artist Sigfredo Chacón, who lives in Miami but travels back to Venezuela frequently, says that artists are also recording history by documenting the protests in photography and video. In addition to fashioning shields for protesters, Dilia Hernández, director of the foundation devoted to the work of Venezuelan Modernist Oswaldo Vigas, has provided food for demonstrators for days on end.

The regime has used torture and censorship to strike back at its critics. Venezuelans publicly criticizing the government from abroad may be refused entry; if allowed in, they may find their passports canceled. (Even so, everyone interviewed for this article volunteered to speak on the record.)

Scarce flights and rising ticket costs are constricting artists’ opportunities to exhibit, says Gabriela Benaim, owner of GBG Arts, one of the few galleries remaining open in the nation’s capital. Her artists have fled to places like New York, Paris, and Buenos Aires. According to Hernández, those shipping artworks out of the country may find them destroyed or confiscated by customs officials.

Even under these crushing conditions, the art community is pressing forward, says writer Raquel Abend, currently at work on an art history PhD in Houston: “In a country where there is no paper, we are still printing catalogues. In a country where we can’t find medicine, we are still organizing exhibitions.”

A Steady Decline of State Funding

Caracas was the cultural capital of South America throughout much of the 20th century and up until the 1990s, say all those interviewed for this story. The country had healthy state funding for the arts, including grants for artists to travel and study abroad. Museums were free and offered lively public programming. In 1968, a project by painter Jacobo Borges received $1 million in government support, according to Gabriela Rangel, director of visual arts at the Americas Society. Even recently, from 2006 to 2014, Caracas had enough local collectors and international pull to host the Iberoamerican Art Fair FIA.

Under Chávez and Maduro, government support for the arts dried up. Contemporary artists are considered enemies of the state, Chacón says, because the regime considers them to be influenced by capitalism. These days, national museums are often closed, with no budgets to pay their staffs or conserve their collections; if open, they often exhibit state propaganda.

“It’s a nightmare,” Hernández says. “The staff are still going to work for now, but they might make $30 a month. That will pay for one chicken. Why keep going to work just to be able to buy one chicken?”

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros poses with Nylon Cube by Venezuelan artist Jesus Soto at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2014. Photo by Matthew Lloyd/Getty Images.

Since the withdrawal of state funding, private arts patronage has become more crucial.

One of Latin America’s best-known art collector-philanthropists is Venezuelan-born Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. Since 1999, she has promoted artists from her country and other Latin American nations through award-winning traveling exhibitions and major gifts to museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Other private or corporate bodies, like the Colección Mercantil Arte y Cultura, with large holdings of Venezuelan art, and the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection in Miami, have also been key, lending art internationally. These collections have supported exhibitions such as “Embracing Modernity: Venezuelan Geometric Abstraction,” at the Frost Art Museum in Miami and “Contesting Modernity: Informalism in Venezuela, 1955−1975” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Venezuela-born artist Patricia Van Dalen called the Houston show “a revelation even for me,” while critic John Yau said it was nothing less than “a rescue mission for Venezuelan modernism.”

A Post-Maduro Future?

Still, Venezuelans are confident that the country will turn around soon.

Though he calls the last two decades “the worst time in the country’s history,” Antonio Gustavo Ascaso, sales director at Ascaso Gallery (with locations in Caracas and Miami), says that he and his colleagues “have hope that Maduro will soon be out of office.” Once that happens, he says, collectors who have been hesitant to spend will begin to support artists again. “People will go back” when the dictatorship ends, says Alejandra Mendez, director of GBG Arts.

In the meantime, galleries are conducting charity auctions, often in coordination with nonprofits, to support organizations like those advocating for political prisoners. “That situation is getting worse every day,” says Eugenia Sucre, director at Henrique Faria Fine Art, with galleries in New York and Buenos Aires.

“We have so many projects waiting” for the moment Guaidó takes power, says Benaim. “We are going to change this country.”