The world watched today as the Donald Trump impeachment hearings took a surprise turn when Ambassador to the European Union Gordon Sondland essentially flipped on the President. Pundits (and John Dean himself) called it a “John Dean moment,” referring to the testimony of the former White House counsel to Richard Nixon, who cooperated with prosecutors and implicated Nixon in the Watergate cover-up.

With current and past impeachments very much in the air, Gallery 98 Bowery in New York, an online outfit that deals in “art ephemera from the 1960s to the 1990s,” is hosting a timely online exhibition: pastel drawings made by courtroom artist Freda Reiter during the mid-1970s trials of close Nixon advisors and collaborators, John N. Mitchell, H. R. Haldeman, and John D. Ehrlichman. (Nixon, of course, avoided the courtroom by resigning from the presidency in August of 1974.)

Freda Reiter, St. Clair petitions Supreme Court (1974). Gallery 98 Bowery’s site states: “Nixon’s refusal to hand over the White House Tapes, under a claim of ‘executive privilege,’ led to the Supreme Court case United States vs. Nixon. White House special counsel James St. Clair’s arguments proved unsuccessful, with the Supreme Court ruling against the president on July 24, 1974.”

“Obviously, there are parallels,” says Marc H. Miller, the curator and gallerist behind Gallery 98 Bowery, on a phone call with Artnet News.

Miller says there has been a lot of interest in Reiter’s pastels lately, likely a result of the renewed interest in impeachments, but also because the images are simply very good. “She’s an extremely talented artist,” Miller continues. “That drawing of Halderman listening in on the headphones is just a stunning picture.”

Freda Reiter, Haldeman listens to Nixon White House tapes (1974). “Central to the court case were Nixon’s secret White House audiotapes, admitted as evidence after the Supreme Court’s ruling on July 24, 1974. Headphones were distributed to everybody in the courtroom,” the gallery states.

Miller says that the historical value of these drawings is remarkable, with Reiter capturing some of the only direct depictions of one of the greatest denouements in American history. Reiter was given access to the courtroom as the official courtroom artist for ABC News.

“They could show the news commentator, or they could use one of Freida Reiter’s pastels,” says Miller. “A courtroom illustrator like Reiter, her greatest value came as part of the judicial process in the courtrooms where photographers weren’t allowed back then.”

Freda Reiter, Nixon’s attorney, James D. St. Clair (c. 1974). “The Watergate trials marked a high point for the practice of courtroom illustration and Freda Reiter was one of the best in the field,” copy on the Gallery 98 Bowery site states. “The museum-worthy drawings being sold by Gallery 98 are priced from $1600 to $3200.”

When ABC initially sent Reiter, who passed away in 1986, to cover the trials, the courtroom artist didn’t expect it to become such an epic commitment.

“She didn’t even live in Washington, D.C.,” says Miller. “My understanding was that she lived in Jersey and they asked her to go down for the early moments, and she found herself there for an almost two-year period.”

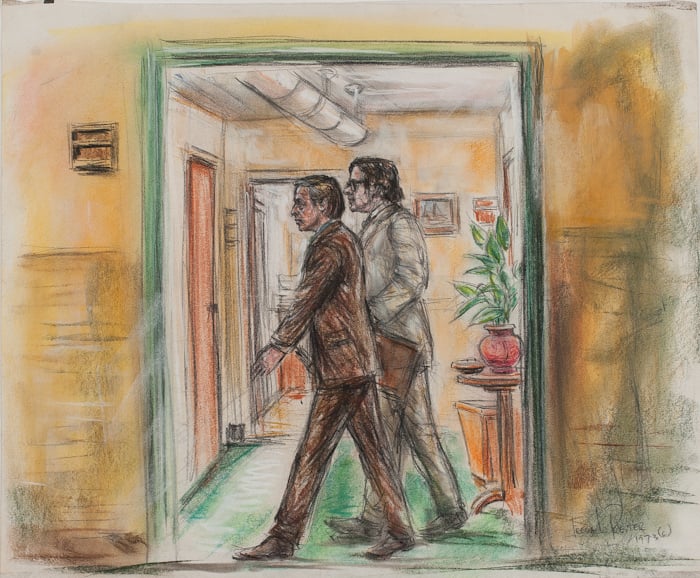

Freda Reiter, Guards Outside Grand Jury Room (c.1973). “The secrecy of the grand jury hearings added even more suspense to the Watergate story. Barred from the proceedings, Reiter captured the heightened security and tension around the proceedings, as in this drawing of two guards outside the grand jury room.”

Miller points out a few pastels that have particular historical relevance. That includes a drawing of James D. St. Clair, Nixon’s attorney, before the Supreme Court during the hearings to decide whether the infamous “Nixon tapes” would be released; and one of Judge John Sirica, who presided over the trials of the Watergate burglars, instructing jurors. In certain other drawings, Reiter imagines Nixon himself, in the midst of phone conversations that were central to the trials.

Miller, who was a curator at the Queens Museum when the Watergate scandal broke, first developed an interest in courtroom drawings through Harper’s Weekly, a fin-de-siecle political magazine that had a brief resurrection in the 1970s. When he saw a small ad for an auction of Reiter’s estate in Philadelphia, he hopped on Amtrak to attend the sale, where he purchased the Watergate drawings and dug through Reiter’s vast archives.

Freda Reiter, Alone in Oval Office (1975). “This pastel imagines Nixon shedding a tear as he prepares to sign his letter of resignation. While the resignation took place on August 9, 1974, the drawing is dated 1975. Reiter might have prepared the drawing for a television program recapping the Watergate saga.”

“I decided to focus on the Watergate ones because I was buying them as an investment,” he says. “I regret a few things I passed up: a batch from around Sandra Day O’Connor’s appointment and presence on the Supreme Court, and some of Patty Hearst’s trial. Most of the trials covered that were topical at the time have faded, but it seemed clear to me that Watergate would have continued currency.”