The contemporary African art fair 1-54 made its African debut in Marrakesh, Morocco, in the Grand Salon of the ritzy La Mamounia, one of Winston Churchill’s favorite hotels. Held over the weekend, 1-54 welcomed 4,000 visitors to view the offerings of 17 international galleries, which exhibited more than 60 contemporary artists from across Africa and its diaspora. Sales were strong, but with the exception of a few rising stars, prices generally ranged from $1,000–20,000—still lower than other markets. That dynamic has many wondering what the fertile African art scene still needs to do in order for the market to fully blossom.

The fair was heaving with international collectors while high-profile museum directors and curators made the trip to Marrakesh. The director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Glenn Lowry, and the Tate’s Zoe Whitley, who co-curated “Soul of a Nation” with Mark Godfrey, were spotted roaming the booths. The fair also reported attendance from directors and curators from The Smithsonian, Zeitz MOCAA and Centre Pompidou.

The past 10 years has seen a growing market interest in contemporary African art. Many blue-chip galleries now represent African artists, and initiatives like 1-54—which launched in London in 2013 and crossed the pond to New York in 2015—are drawing in international collectors in droves.

Marrakesh is traditionally a link between Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. French is most Moroccans’ second tongue, so the location lured numerous Francophone exhibitors and collectors not guaranteed to appear in the New York edition of the fair in the spring or in the London iteration in the fall.

Fair director Touria El Glaoui, center. Courtesy of 1-54.

“I think there’s a high correlation between the economics of a country and how the artistic scene is developing,” fair director Touria El Glaoui told artnet News when asked about the different scenes across the continent. “We’re dealing with the whole continent, not one country, and they’re all at different levels of development.”

According to El Glaoui, who is also the daughter of Moroccan painter Hassan El Glaoui, North Africa has developed a strong artistic scene over the past 20 years, with auction houses popping up around Morocco, and some 10 galleries per big city. Many of them are now doing international art fairs, and Moroccan artists are commanding high values for their art.

The 2018 edition of the Marrakesh Biennale, which was due to take place this month, was cancelled in September last year due to the withdrawal of sponsors. But the local gallery scene is vibrant, with galleries like Comptoir des Mines and Gallery 127 in the city’s Guéliz neighborhood buzzing with locals, as well as artists and art lovers drawn into the city for the fair. The city’s newly opened Yves Saint Laurent museum and the first museum dedicated to contemporary African art also drew crowds.

Yamou, Double Ciel (Double Sky) (2017). Courtesy of L’atelier 21.

Moroccan gallerists were well represented at the fair. Loft Art Gallery, from Casablanca, founded by young gallerists Myriem and Yasmine Berrada in 2009, took part in the fair for the first time. Loft brought two Moroccan artists, Hicham Benohoud and France-based Mohamed Lekleti, and an Ivorian artist called Joana Choumali, who lives in Abidjan but studied and lived in Morocco for several years. “Our selection is a synthesis of the Moroccan creativity,” the gallery’s development manager, Jacques-Antoine Gannat, told artnet News, adding that it reflects the “incredible diversity of the Kingdom, artistically but also culturally and historically.”

Also making an appearance from Casablanca was 10-year-old L’Atelier 21 presenting work by a roster of all-Moroccan artists. They included Mohamed Abouelouakar, who turned to painting after a career in filmmaking, and Yamou, who lives and works between Paris and Morocco and whose work is inspired by organic processes.

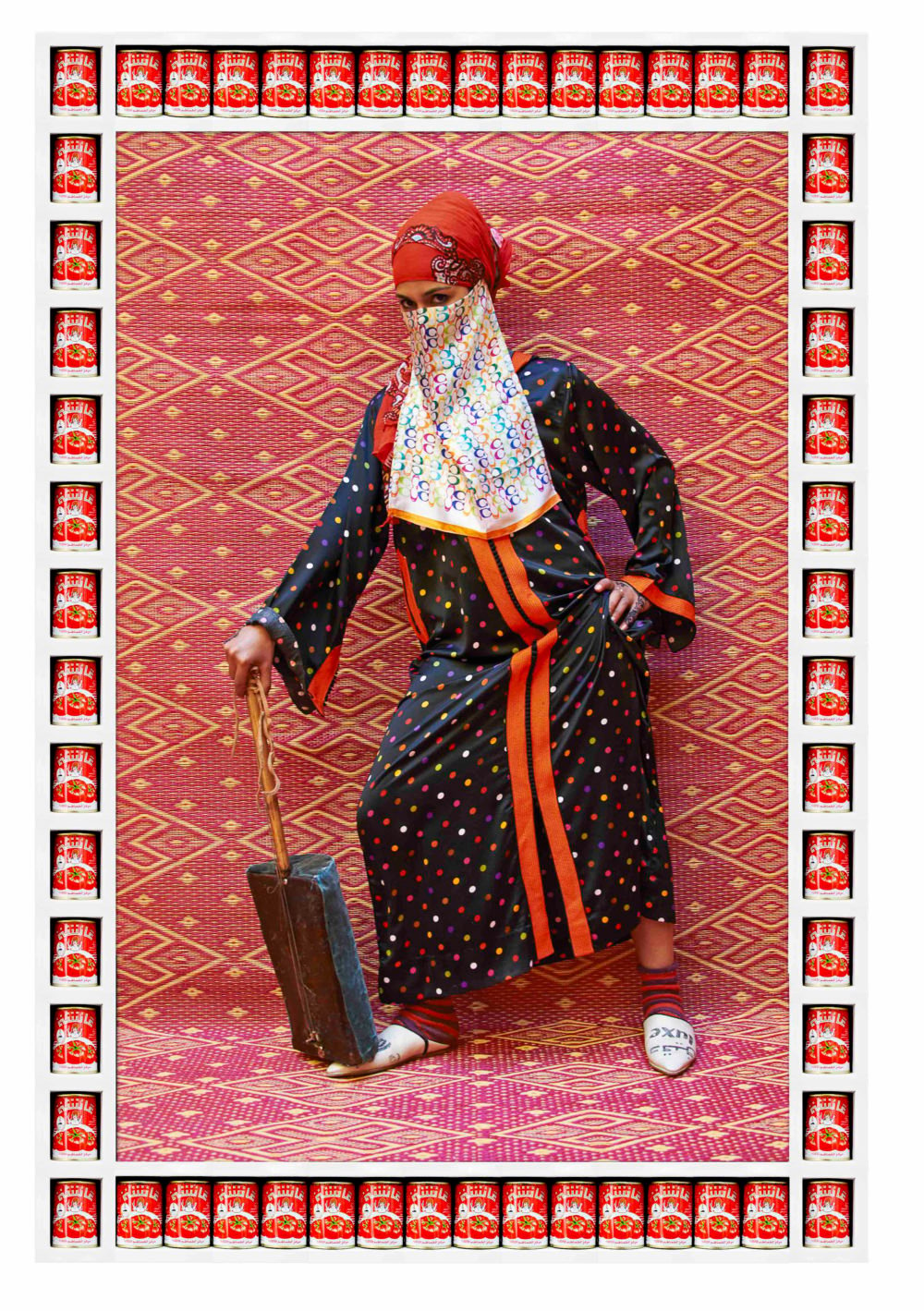

Other Moroccan artists of note were Mahi Binebine at Sulger-Buel Lovell—who has reached as much as $210,000 at auction, according to the artnet price database—and Hassan Hajjaj, the “Moroccan Andy Warhol.” Hajjaj told artnet News that London’s Vigo gallery had sold his one work at the fair, a 2012 photograph titled Marmouche, framed with arabic-laden tomato soup cans.

Installation shot of VOICE Gallery’s stand. Courtesy of 1-54.

The only gallery actually from Marrakesh was seven-year-old VOICE gallery, which brought Sara Ouhaddou, who was raised in France in a Moroccan family, and Algerian artist Eric van Hove. Gallery director Rocco Orlacchio told artnet News he chose these artists for the first edition of the fair in Marrakesh because while their work differs vastly to each others, they both have a strong connection with the craft tradition in Morocco. Aside from attracting collectors, he also said that he hopes the fair will draw other artists to the region. When asked what he thought the contemporary African art market needs to grow, he answered simply: “Quality, and institutional interest.”

Among local collectors at the fair were Othman Lazraq, the president of Marrakesh’s newly opened Museum of African Contemporary Art (MACAAL), which houses the Lazraq family’s collection of contemporary African art. Lazraq used the buzz around 1-54 to relaunch his museum on the edge of the city, which has attracted around 5,000 visitors since its soft launch last year. He and his father Alami are both on the acquisition committee for the museum, and have purchased from 1-54 before, notably an Abdoulaye Konaté work showing at the museum.

Installation shot of Blain Southern’s stand. Courtesy of 1-54.

Marwan Zakhem, an Accra-based construction entrepreneur who has been collecting for 17 years, and is on Tate’s Africa Acquisitions committee, was also there. Two years ago he also opened Gallery 1957, named for the year Ghana gained independence from the British, and one of his artists, Elisabeth Efua Sutherland, was also in the city with an arresting performance titled Black Noise.

As to the scene in Ghana, he said that the country still lacks the collector base and infrastructure that a more mature market like Morocco’s thrives on, but that it is slowly building one. “I think we’re still scratching the surface, obviously, but we do have now pretty established names, successful West African names like El Anatsui, and Ibrahim Mahama, are becoming household names”

Although Zakhem’s gallery has taken part in other editions of the fair, he skipped out on Marrakesh. Speaking to the glut of art fairs in the yearly calendar, he explained: “We’re actually doing Art Dubai next month, 1-54 New York in May, then London, and we were going to do Dallas Art Fair in April, so it was just too much,” adding: “It’s nice to come to a fair and not have something to do. You know, really to just be able to see the other angles, to come in as a collector, a supporter, and have a little bit of fun.” Zakhem made an offer on two pieces on the second day of the fair, but they had both already sold.

Other galleries from West Africa did make an appearance at the fair, including Art Twenty One, from Lagos, Nigeria, which showed metal sculptures by Nigerian artist Olu Amoda, and photographs by Swiss-Guinean artist Namsa Leuba. Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, from Abidjan in Ivory Coast, which has participated in the fair since its first edition in 2013, brought work by Ivorian artist Aboudia, and photographs by French-born François-Xavier Gbré, who is based in Abidjan, among others. Also representing from Abidjan was LouiSimone Guirandou Gallery, founded by art historian Simone Guirandou-N’Diaye in 2015.

Installation shot of Sulger Buel–Lovell ’s stand. Courtesy 1-54.

London- and Berlin-based Blain|Southern gallery was taking part for the first time. Laetitia Catoir, one of the gallery’s directors, told artnet News they made a number of new contacts among the regional and international collectors attracted to the fair. “The fair has a relaxed pace of sales, which stretched well into the weekend, and we had interest from the outset in the works by Moshekwa Langa and Abdoulaye Konaté.” She added that the strong interest in Konaté (whose prices range from $55,000–105,000) was buoyed the unveiling of his work at MACAAL. Both Konaté works are on reserve, and alongside institutional interest, there will be several new commissions.

Before the fair was through, Milanese gallery Officine dell’Immagine had almost sold out their booth, surrendering eight works—by Mounir Fatmi, Safaa Erruas, and Farah Khelil and priced between $2,000 and $18,000—to international collectors.

London-based Sulger-Buel Lovell, founded four years ago by collector Christian Sulger-Buel and gallerist Tamzin Lovell Miller, showed Senegalese painter Soly Cissé, and stunning folkloric paintings by Tunisian artist Slimen El Kamel. A gallery spokesperson told us that sales were going well, and the booth was drawing in buyers and collectors from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and the US.

Farah Khelil, IQRA (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Officine dell’Immagine.

Omar Berrada—who will also take the lead on the talks program in the New York edition of 1-54 in May—curated the fair’s Forum talks program, titled “Always Decolonize!” Among other things, the talks suggested that not looking at the continent as a homogenous lump, or in the broad strokes of territories carved out by colonialists years ago, might help the distinct African markets to develop.

The artistic scenes in Africa differ vastly from country to country. As far as contemporary art goes, South Africa has taken the lead in recent years, with Zeitz MOCAA opening in Cape Town last year, and the appearance of fairs like Cape Town Art Fair and Joburg. Nigeria has also seen a wealth boom related to oil, which has fostered an art scene, evinced by the founding of international contemporary art fair Art X LAGOS in 2015. The Egyptian art scene is also lively, with Cairo Art Fair now entering its fourth year.

Indeed, the variety of work showed that “African art” is a clumsy handle. Although it has often been essentialized in art history, Africa, after all, is made up of 54 countries. Here, a nuanced interpretation of African art is on view. Stories that tell of any African experience vastly differ from country to country, as does work guided by the experience of the being part of the diaspora.

But pushing the growth of the market through dedicated fairs and sales is just the first step. The next step is to integrate art from the continent into the market without seeing it being in a different league, lifting the longstanding geographical paradigms to reflect contemporary artistic scenes and movements. The strong sales show that 1-54 is a fair to be reckoned with; its presence on the art-world calendar continues to boost international visibility for African artists, which will ultimately translate into the market.

This, however, will take time, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “Obviously, we don’t want a bubble, an accelerating craziness like China, or South America,” said El Glaoui. “My desire is that it is a continuous, constant growth rather than any kind of boom.”