Édouard Manet (1832–1883) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) were peers, friends, and rivals.

The two French painters played a crucial role in the new painting that emerged between the 1860s and 1880s in Paris, but each had strikingly different personalities and artistic approaches. A new blockbuster exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in the French capital (on view through July 23) highlights their overlapping interests and individual techniques through exciting juxtapositions of their masterpieces. The groundbreaking show will later travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Both artists were born into bourgeois backgrounds. But whereas the extroverted Manet was highly driven towards recognition, the more introverted Degas often eschewed official channels of legitimacy. While they shared certain interests—such as depictions of café scenes, prostitution, nudes in bathtubs, and horse racing—they portrayed these genres in contrasting ways. Manet made audacious paintings reinventing realism and Degas focused on developing a slightly more intimate style. Both of them made a significant mark on art history in the lead-up to Impressionism, a movement with which they later became associated.

Artnet News spoke to Isolde Pludermacher, chief curator of painting at the Musée d’Orsay, about five pairings of paintings in the exhibition that illuminate the relationship between these two master painters.

Degas’s Femme sur une terrasse (1857–58, reworked 1866–68) and Manet’s Jeune dame (1866)

(L) Edouard Manet Jeune dame (1866). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (R) Edgar Degas Femme sur une terrasse (1857–58). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Isolde Pludermacher: “Manet made his painting for a salon in reaction to a painting, La Femme au perroquet (1866), by Gustave Courbet whom Manet was more in dialogue with at the time, whereas Degas’ work was made from a study. Manet’s association of a young woman with a pet could recall his painting Olympia (1863), which features a small black dog. In both paintings, it’s the same model, Victorine Meurent, who also posed for Manet’s painting Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863). Manet evokes the young woman’s intimacy as if the parrot could be her confidant; the parrot is gray and all the color is focused on the model’s dress.

Meanwhile, Degas’s work [also known as Jeune femme et ibis] wasn’t destined to be seen by a lot of people. Initially, it simply depicted a young woman wrapped in a blue cloak standing on a terrace. Around a decade later, he added two flamboyant pink ibis birds, a sunset, and an imaginary town evoking Babylon. The inspiration is very symbolic, close to the Pre-Raphaelites, and might have been inspired by Gustave Moreau who’d suggested to Degas the idea of painting a young Egyptian woman feeding ibis.

What interests us is that Degas had seen Manet’s painting in the 1868 salon and made a sketch inspired by it. He might have incorporated the ibis into his work afterwards. There’s a mysterious and enigmatic dimension to Degas’ painting where the birds are free, while the parrot in Manet’s painting is domestic and inside a bourgeois interior.”

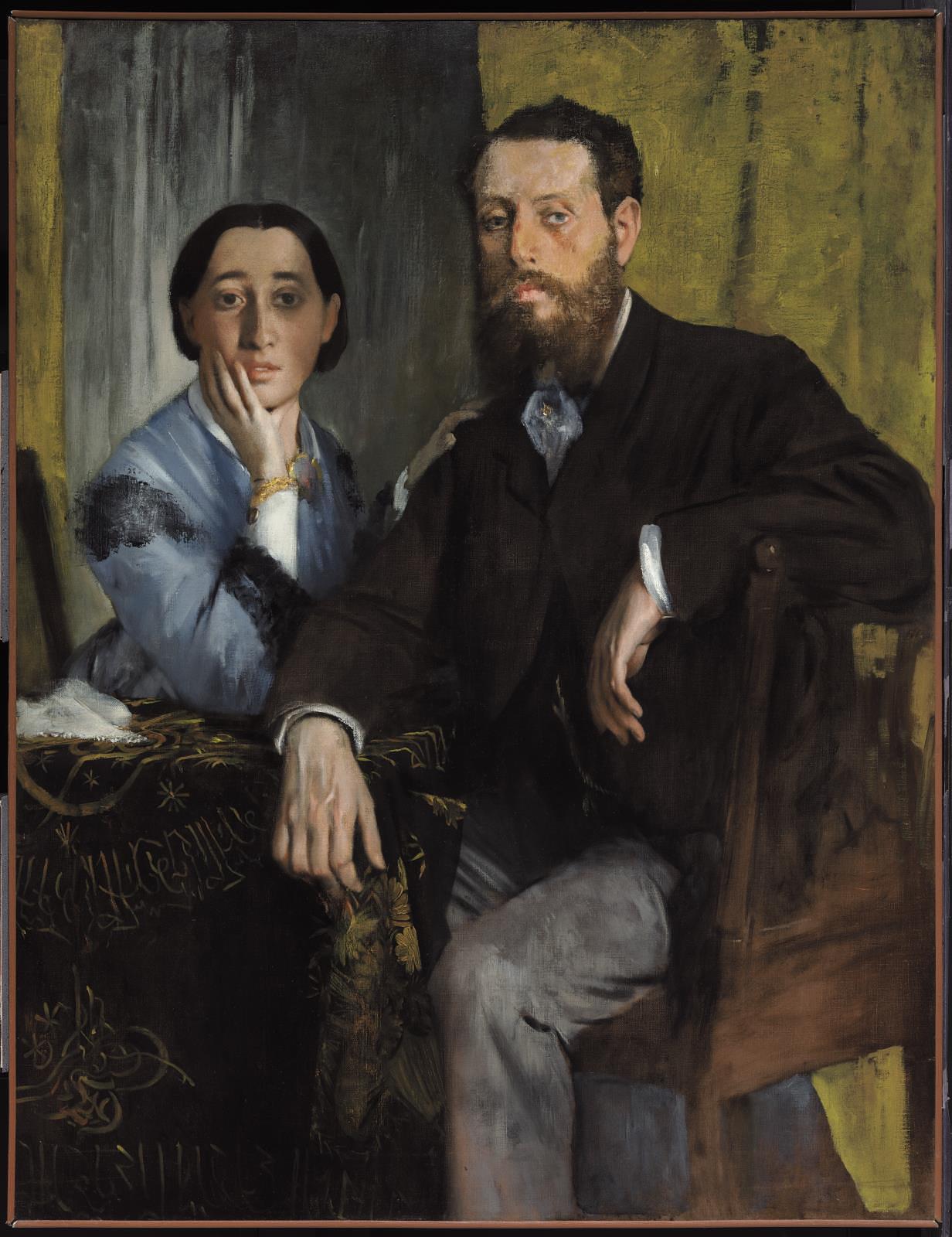

Degas’s Monsieur et Madame Manet (ca. 1868–69) and Manet’s Madame Manet au piano (1868)

(L) Edgar Degas Monsieur et Madame Manet (1868–69). Kitakyushu, Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art, Japan © Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art. (R) Edouard Manet Madame Manet au piano (1868). © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt.

Isolde Pludermacher: “This pairing is among the most interesting stories to explore the relationship between Manet and Degas. We imagine that Manet made his painting after that of Degas but don’t know for certain. Degas made the portrait of Manet [on the sofa] and his wife playing the piano at their home and offered it to his models. The Manets organized a lot of parties on Thursday evenings to which they invited their artist friends and we can see this sociability through the painting.

One day, Degas went round to Manet’s and saw that his painting had been cut at the level of the wife’s face. [Manet had cut it because he believed his wife had been rendered “excessively ugly”.] Degas angrily took the painting back and returned a still-life that Manet had given him.

Fascinatingly, Degas kept the [Monsieur et Madame Manet] painting all his life. At the end of the exhibition, there’s a large photograph of Degas in his apartment with the painting on his living room wall. Around 15 years after Manet’s death, Degas added a piece of canvas to complete the missing part of Madame Manet and it was found like this in Degas’s studio after his death.”

Degas’s Portrait de Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet ‘La Source’ (ca. 1867–68) and Manet’s Lola de Valence (1862)

(L) Edouard Manet Lola de Valence (1862). © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt (R) Edgar Degas Portrait of Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source” (1867–68). Gift of James H. Post, A. Augustus Healy, and John T. Underwood. Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn © Brooklyn Museum.

Isolde Pludermacher: “What we wanted to show through this pairing is that the two artists, with different techniques, propose a comparable mise-en-scène, both depicting celebrity dancers. In Manet’s painting, it’s a Spanish dancer who was part of a Spanish troupe performing in Paris. In Degas’ painting, it’s an opera dancer, Eugénie Fiocre, who was very famous, notably for her beauty. Neither painting shows the dancer on the stage. In Lola de Valence, it’s [backstage] just before she goes on stage.

In the painting of Fiocre, it’s during a rehearsal break—she’s in a moment of reverie, her ballet pumps beside her, and a figure behind her is playing music. So both artists were interested in sideline moments. Degas obviously had a very particular relationship to dance. He captured the repetition of certain bodily gestures and postures in a singular way. By contrast, Manet was more traditional in the way that he asked his different models to pose.”

Degas’s Scène de Steeple chase (1866, reworked in 1880–1881 and 1897) and Manet’s L’homme mort (1864)

(L) Edgar Degas Scène de Steeple chase (1866). National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. (R) Edouard Manet L’homme mort (1864). National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Isolde Pludermacher: “Both these paintings are on loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, but have never been shown together before. The pairing is a very striking example of the proximity between the two artists.

Manet exhibited a painting [Incident in a Bullfight] in the Paris salon [in 1864] representing a corrida scene with a dead toreador in the foreground and the corrida in the background. Its perspective was harshly criticized and so Manet cut it into two in order to make a stronger, more powerful image of the dead man. The other part of the painting [The Bullfight] is in the Frick Collection, New York.

Degas’s painting, Scène de Steeple chase, is undoubtedly inspired by Manet. It’s a salon painting too. The horse-racing theme is particularly important for the two artists and symbolically interesting. At the end of the 1860s, Manet went to England and wanted Degas to go with him to the horse races and sell [ensuing paintings] on the English market but Degas declined.”

Degas’s Dans un café (1875–76) and Manet’s La Prune (1877)

Edouard Manet La prune. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Edgar Degas Dans un café or L’absinthe (1875–76). Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. ©Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt.

Isolde Pludermacher: “It’s a really interesting, lovely confrontation because it’s the same model—the actress Ellen André—in the same bar, La Nouvelle Athènes [in Place Pigalle]. It’s where artists and writers hung out, and Manet and Degas went there every day.

Both paintings were made in the 1870s, later than other paintings in the exhibition. Degas made his first, and showed it in an Impressionist exhibition, and perhaps it inspired Manet.

Even though the model is in the center of Degas’s painting [also known as L’Absinthe] she seems to be in the background. He’s depicted her as if she’s under the influence of alcohol, forlorn, and like a prostitute. Degas was interested in an oblique perspective, her feet and a play on mirrors. In Manet’s painting, the same woman is barely recognizable. She’s traditionally in the center of the composition, also in front of an alcoholic drink, but there’s a gracious pose and a beauty of colors that enhance her.”

“Manet/Degas” is on view at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris through July 23, 2023.