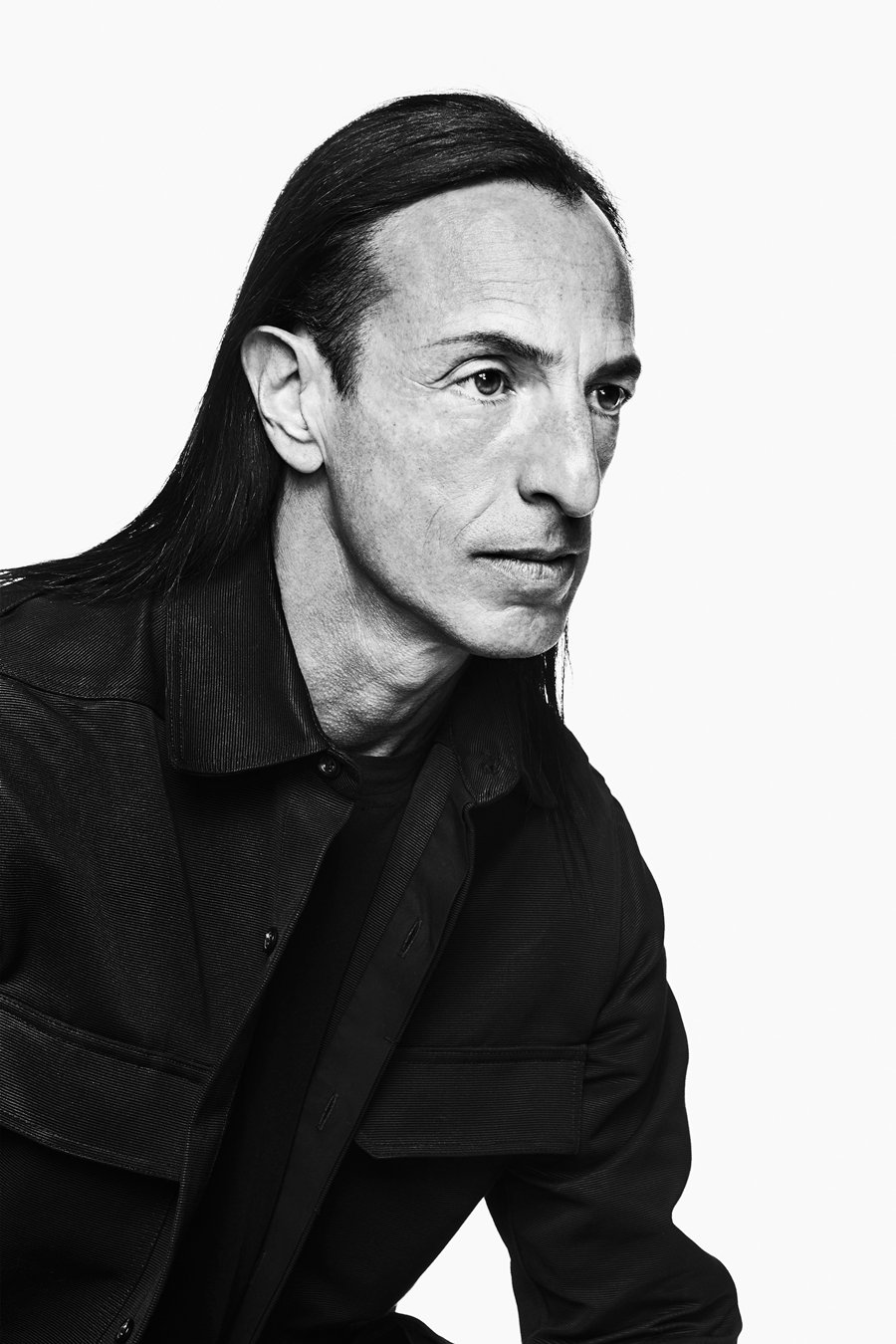

The American fashion designer Rick Owens occupies a mythical place in the minds of many: his personal evolution from West Coast miscreant to the dark horse of Paris fashion has been driven by a strict, unrelenting devotion to re-thinking the human vestment. Owens’s approach is less “Why?” than “Why not?”—a questing process that has led him to fuse nature’s finest materials (paper-thin lambskin, raw cut silks) and mankind’s more monumental inclinations (be those architectural, cinematic, musical, or otherwise) to create clothing that has genuinely shifted the fashion dial forward, both for the subcultures he has nurtured and for the field at large.

That said, Owens will be the first to admit that his work has been pigeonholed. “For the rest of my life I’m going to be the sneakers-and-baggy-shorts guy in black,” he says. “But I should be grateful to be recognized for anything at all, so being able to elaborate on it is just icing on the cake.”

Installation view of “Rick Owens: Subhuman Inhuman Superhuman” at the Triennale di Milano. © 2018 Owenscorp.

Speaking to artnet News from his label’s production HQ in Concordia (a small town in Modena, Italy), Owens is referring to “Subhuman Inhuman Superhuman“—his first retrospective exhibition, currently on view at the Triennale di Milano, which provides ample opportunity for the designer to “elaborate” on his life’s work. From afar, it seems an incongruous venue for the expat Parisian’s first foray into public nostalgia, but Owens’s links with Italy are many, and the rare freedom granted to him by the prestigious design museum was impossible to refuse. “I agreed to it as I didn’t have any interaction with other curators at all,” he says. “That was the only appeal in doing it. I’m not good at negotiating, compromising, and listening to other people so it would have been very frustrating.”

Born from that curatorial freedom, Owens’s show is a sprawling autobiography, occupying the Triennale’s curved gallery with tableaux and tall pedestals holding mannequins draped in his creations—all of it arranged not chronologically, but chromatically. In shades of bone white, pearl grey, khaki, and stark black, outfits are nuanced with exquisite details: protruding forms of copper leather, strict rows of bugle beads, geometric arrangements of horn, stripes of mink, and cascading jersey pleats reminiscent of the work of Madame Grès or Madeleine Vionnet.

In vitrines nearby, Owens tells his story through an intimate curation of personal paraphernalia, from jewelry and invitations to photography and fashion shows to more exotic pieces like bone cutlery and a reusable cock ring fashioned from a goat’s eyelid (a product that the designer commercialized in 2008, sold in a toadskin case). Though Owens’s furniture line is present, it takes a backseat, with his costlier creations in petrified wood, ox bone, antler, and alabaster eschewed in favor of more robust camelhair modules scattered throughout.

What follows is a conversation with Rick Owens about his show, and the inspirations behind it.

Left: India, FW17 Glitter Womens. Photo: Danielle Levitt. Right: Installation view of “Rick Owens. Subhuman Inhuman Superhuman.” © 2018 Owenscorp.

Where are you at the moment, Rick?

I’m on my terrace in Concordia. It’s overgrown with jasmine plants. I don’t trim them, so I let them go wild. I have a Greta Garbo movie playing and I just got off the phone with Michele [Lamy] who is in London for her LamyLand boxing world project.

Most people think that you live full time in Paris, but in fact you are often in Venice, or Concordia, right?

I spend about five months a year in Venice now, from about May to September so I don’t need to go there in winter. Besides, the dock is closed to the Excelsior, which is where I order all my food!

So, showing your first retrospective in Italy wasn’t such a left-field move after all.

The whole thing of having that show in Milan just seemed very resolved—it made perfect sense to me. This brand is Italian, in the end, although I’m not really familiar with Milan, as I haven’t done a lot of business there. We have a store there, but I’ve always shown in Paris. I love the way Milan looks, though: the severity, the shagginess. They have a shaggy way the plants drip off the balconies. Paris is a little bit more groomed. With all that stone and all that grayness and the severity, it is kind of stern. I could totally live in Milan. For me the train station really sets the tone for the city. For the party we had, we were looking at spaces in the train station, but in the end, there were too many issues with the entrances. Did you come to the party?

Yes, I think I saw you backstage with those white-painted fan dancers, just as they took their underwear off to perform.

(Laughs) Well, originally, I wanted to find original leather-daddy fan dancers from San Francisco, but now those guys do this new flag dancing that just wasn’t old-school enough. And I wanted them to be naked because it was supposed to be complete hedonism, to honor the queer forefathers that suffered a lot. I thought, “This is a fashion party in Milan, it has to be full-on!” They were pretty great, but they had to learn fan dancing. It can be very intricate! And they had beards! Guys have beards these days. So we extended them!

Installation view of “Rick Owens: Subhuman Inhuman Superhuman” at the Triennale di Milano. © 2018 Owenscorp.

Do you consider yourself to have any relationship to Italian design? It’s funny to consider that there’s an Ettore Sottsass show at the Triennale coinciding with yours.

I liked Luigi Colani at the time of Sottsass—he’s the one I identify with the most in Italian design. I really love his work. He reminds me of that ’70s Brutalist moment with Domus magazine at that time. I think I first saw that magazine when I was at art school in LA. And I always liked the old stuff like Carlo Scarpa, and Luigi Moretti especially.

How did it feel to curate your own retrospective? To see this kind of show for a living artist or designer, and from their own perspective, is rare.

Obviously, it makes you aware of your mortality and it presses some buttons there about what you’ve achieved, and it’s easy to get a little bit melancholy. But that feels a little silly, so I preferred to completely relish it and wallow in it. You do think about the meaning of your life and what you will be remembered for and all of that. It’s really very satisfying. And the most important thing is being able to tell the story on my own terms, instead of having it being interpreted by someone else, which would never be perfect. Being able to tell your own story is an amazing thing. It doesn’t happen all the time, to be able to highlight your strengths and discretely sweep away your mistakes.

It was a weird year as I also received the CFDA lifetime achievement award. Both of those things have nothing to do with each other, but they’re such strong moments of lifetime achievement that it was such a weird coincidence. I’m 56, which isn’t really that old and it was really validating and satisfying. I’m not going to sneer at the fact that I am being recognized by the establishment. As you become older, you become the establishment. It’s interesting to be recognized as part of this generation’s aesthetic elite.

In terms of the garments on display, I was wondering why the oldest pieces of the show only date back to 2005–06? Was there a pragmatic constraint there, in regard to your archives?

Yes. Literally it was because I didn’t have any archives! Originally, my label was a license, so the samples technically weren’t even mine, so they got sold or disappeared. The archives weren’t in my head. I didn’t think I was that kind of designer. I would have been embarrassed to save things for archives in the beginning. So things literally disappeared—even what Michele had. Michele gives things away when she gets tired of them. She gives something to her daughter, then it goes to someone else. I think if I ever do another show maybe I would do one that was a little bit more discreet and more restrained and more about craft and technique and cut and the details. This one was more theatrical and big, and if I ever did a show that was more restrained, then it would be a good time to hunt down things that looked really loved, and really used.

The show’s set design is a big part of that theatricality. You’ve said it’s a response to your own words: “I would lay a black glittering turd on the white landscape of conformity.”

Guy Trebay wrote something in the Times a few years ago, well before the Triennale approached me for the retrospective. He wrote about my work, and he brought up that thing that I had said over 20 years ago so, so I guess it was in my mind. And the space itself was architecturally right up my alley. It seemed that placing a huge, primal, sweeping gesture in there was the right thing to do. Michele thought it was really lame, she turned her nose up at it and said it was “first degree.” I did it because a lot of the things I have done are simple gestures and I like that. It was a flourish that made sense with my love of Land Art and of something primitive in this graceful curve. I referred to it as a “Primal Howl.” The working title was the “Turdnado.” It gets cheap and it gets comical.

Installation view of “Rick Owens. Subhuman Inhuman Superhuman” at the Triennale di Milano. © 2018 Owenscorp.

Can you explain the composition of the “Primal Howl” piece? I believe it’s made from your own hair, sand from the Adriatic Sea, et cetera.

It couldn’t just be foam. It had to mean something that related to my life and that felt personal. The funny thing is that I had been saving up wads of my hair over the years. I really had wads of it from hairbrushes. Of course, there is not a hair in every square inch of it but it is in the mix. It’s about fucking the space with your DNA! The sand is from the area around Venice. It’s the beach that I am on quite a lot, and the seaside. I would be at the seaside all year long if I could. There is something about that intersection of ocean and sea and earth and sky that makes you feel like you are in the center of the universe.

What did you want this show to say, if not to be a didactic A–Z guide to Rick Owens?

There was no real narrative. It is about as graceful a composition as I can find. It’s based on instinct. It was just about scraping together everything that I felt right about, and creating these graceful compositions. I guess I had about 30 percent more that I edited out. It’s like poetry—you try to combine some sentences and some words that reflect off of each other in a beautiful way.

Installation view of “Rick Owens: Subhuman Inhuman Superhuman” at the Triennale di Milano. © 2018 Owenscorp.