When the 20th edition of the World Cup begins in Brazil on June 12, ball artists from 32 countries—including Primitives, Realists, and Incoherents—will be given an opportunity to mount some “true exhibition stuff,” as the saying goes. Soccer and art have, in fact, proved a better match than soccer and film, or soccer and literature, because attempts to impose a dramatic structure on soccer’s inherent and unscriptable drama invariably fails.

What follows are 16 artworks that in entirely different ways catch the essence—or in some cases the tragic ironies—of “the Beautiful Game.”

Du Jin, Chinese ladies playing cuju

The Chinese sport of cuju (“kick ball”) originated as a military training exercise during the Warring States period (476–221 B.C.) and evolved into an upper-class pastime during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220). This painting by Ming Dynasty painter Du Jin (active 1465–1509) shows female courtiers, apparently unbothered by their bound feet, playing cuju in a garden.

Du Jin

Photo: Public domain.

Thomas Webster, Football or The Football Game (1839)

Association football, or soccer, evolved from the English 12th-century mob sport played with a pig’s bladder and ritualized as a Shrove Tuesday festivity. Webster (1800–1886) was a popular Victorian painter of rural village scenes. In this one, and in at least two others, he depicts a rabble of boys bearing down on a nervous little goalkeeper.

Thomas Webster, The Football Game (1839)

Photo: National Football Gallery.

Thomas M.M. Hemy, Sunderland vs. Aston Villa (1895)

One of the first and most detailed English Football League paintings shows Villa attacking the crowded home goalmouth on January 2, 1895. The game ended 4–4. The huge canvas (12 × 8 ½ feet) was commissioned to commemorate Sunderland’s winning of the First Division Championship (now the Premier League) three times in four seasons—1892, 1893, and 1895. Villa, who had won it in ’94, finished third in ’95 but won that year’s FA Cup. Hemy (c. 1850–1937) was primarily a marine painter.

Thomas M.M. Hemy, Sunderland vs. Aston Villa (1895)

Photo: Sunderland AFC.

Umberto Boccioni, Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913)

Successive movements are simultaneous in the work of the foremost Italian Futurist painter and sculptor Boccioni, who synthesized time, place, and matter into vertiginous flurries of color. His 1912 Elasticity, depicting the formidable energy of a horse, preceded 1913–14’s “Dynamism” series, which featured the human body, a cyclist, and “horse + houses,” as well as his speeding soccer player.

Umberto Boccioni, Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913)

Photo: The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection.

Lady Butler, A London Irish at Loos (1916)

Elizabeth Thompson (1846–1933), better known as Lady Butler, was a distinguished painter of British military scenes, her works including The Defence or Rorke’s Drift (1880) and Scotland Forever! (1881). Her avowed intent was not to capture battlefield glory but war’s “pathos and heroism.” Pathos is to the fore in this watercolor depicting Sergeant Frank Edwards of the London Irish, who, against orders, began a passing movement with a leather ball as he and his fellow riflemen headed across no-man’s-land toward the German wire on September 25, 1915. Edwards was shot in the thigh and gas-poisoned, though he survived the war and lived until 1964. Combined British and German casualties at Loos exceeded 110,000. The British offensive failed.

Lady Butler, A London Irish at Loos (1916)

Photo: London Irish Rifles Association.

L.S. Lowry, Going to the Match (1923)

One of Britain’s’ most popular 20th-century painters, Lowry (1887–1976) was born in the Manchester United territory of Old Trafford, Stretford, but fate apparently selected him to be a Manchester City fan. An admirer of Rossetti, Magritte, and Lucian Freud, he painted in a flat, naïve style—the places composites, their people and dogs near-matchsticks—with an Expressionistic undertow. His canvases indelibly capture the rituals and rhythms of Northern working class life—none more important than hurrying to a soccer match for a three o’ clock kickoff on a chilly Saturday afternoon.

L.S. Lowry, Going to the Match (1923)

Photo: National Football Museum.

Photographer unknown, Mme. Bracquemond, c. 1920

Madeleine Bracquemond, captain of France’s national women’s team, posed for an unusually sophisticated early soccer photo. By isolating her in a shadowy studio, the photographer emphasized her concentration and the illusion of motion. Bracquemond led the side that defeated England’s famous Dick, Kerr’s Ladies 2–1 over a four-game 1920 international series. (Dick, Kerr and Company was a Preston manufacturer of tramcars and rolling stock.)

Photographer unknown, Madeleine Bracquemond, c. 1920

William Reginald Howe Browne, Wembley (1923)

The building of England’s Wembley Stadium was completed four days before it hosted the FA Cup Final between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United on April 28, 1923. There was space for 127,000, but thousands more filled the terraces and spilled onto the field. PC George Scorey, mounted on “Billie,” gently pressed the fans to the side so the game could begin—the event subsequently was dubbed “The White Horse Final.” Billie is virtually center of Browne’s painting, on the uppermost edge of the “highest” of the green islands that form an archipelago amid the sea of fans. Bolton won 2-0. The grand old Wembley was demolished in 2003 and replaced by the new one.

William Reginald Howe Browne, Wembley (1923)

Photo: National Football Museum.

Artist unknown, O Vincere o Morire (1950s)

A soccer poster ruefully commemorates the telegrams sent by Benito Mussolini to Italy’s players telling them they must “conquer or die” in the 1938 World Cup final in Paris. Luckily for them, they defeated Hungary 4-2. Italy had won the 1934 tournament on home ground.

Artist unknown, O Vincere o Morire (1950s)

Georg Eisler, Hillsborough (1989)

Eisler’s Expressionist rendering of the Hillsborough stadium disaster in Sheffield, England, was taken from a television screen frame logged at 3.06 pm, April 15, 1989. That afternoon 96 Liverpool fans were suffocated to death as a result of overcrowding at the start of their team’s FA Cup semifinal with Nottingham Forest. The painting shows some fans straining for safety in the tier above the crush—an echo of Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment. Eisler was the son of the Austrian composer Hanns Eisler and a pupil of the Expressionist master Oscar Kokoschka when both were Austrian refugees in wartime London.

Georg Eisler, Hillsborough (1989)

Image: © Walker Art Gallery, courtesy The Public Catalogue Foundation.

Peter Edwards, Bobby Charlton (1991)

Fifteen years after his official retirement, the great Manchester United and England forward relaxes at home. Sir Bobby was a gentleman player—hence the suggestion of a halo. The painting, now in the National Portrait Gallery, was commissioned to celebrate the 25th anniversary of England’s triumphant 1966 World Cup campaign, in which Bobby and his older brother Jack were ever-present.

Peter Edwards, Bobby Charlton (1991)

Image: © Peter Edwards, courtesy The Public Catalogue Foundation.

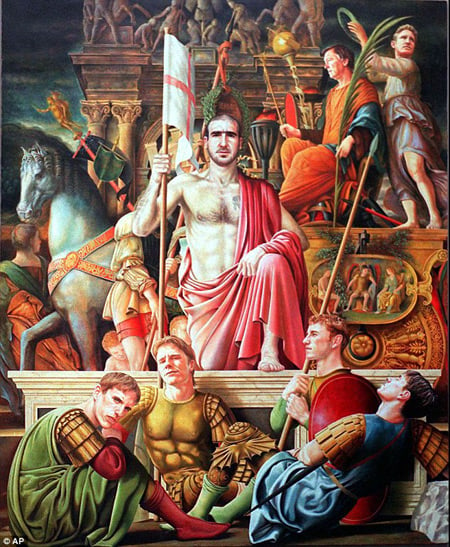

Michael Browne, The Art of the Game (1997)

Browne’s painting glorifies Manchester United’s domination of English soccer in the 1990s. Closely based on Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection (c. 1460), its Jesus is Eric Cantona, United’s virtuosic philosophe; the Roman disciples at his feet are Philip Neville, David Beckham, Nicky Butt, and Gary Neville. Another United player, John Curtis, places a laurel on the head of coach-turned-emperor Alex Ferguson.

Michael Browne, The Art of the Game (1977)

Photo: Michael Browne.

Peter Hodgkinson, The Splash (2004)

Soccer statues are sprouting up everywhere, but none is more imaginative than this tribute to Sir Tom Finney (1922–2014), the legendary 1940s and 1950s Preston and England winger. It was inspired by the English 1956 Sports Photograph of the Year, which shows Finney sliding through a tackle at Chelsea’s waterlogged pitch. Interestingly enough, he maintained his plumbing business throughout his career.

Peter Hodgkinson, The Splash (2004)

Photo: Preston North End Football Club.

Felix Reidenbach, Adidas Fresco, Cologne (2006)

It took Hamburg illustrator Reidenbach 40 days to paint the sportswear corporation’s 9,000 square-foot ad on the ceiling of Cologne Central Station. In appropriating the style and worshipful perspective of Andrea Pozzo’s Baroque masterpiece The Triumph of Sant’ Ignazio of Loyola (1685), which decorates the nave at St. Ignatius Church in Rome, Reidenbach granted contemporary divinity to the following players in the Adidas stable: Michael Ballack, David Beckham, Djibril Cissé, Kaká, Lionel Messi, Nakamura, Lukas Podolski, Raúl, Juan Román Riquelme, and Zinedine Zidane.

Felix Reidenbach, Adidas Fresco, Cologne (2006)

Photo: Adidas.

Jessica Hiltout, Happy Soko FC, Malawi (2010)

In 2002 Anglo-Belgian photographer Hiltout abandoned advertising, bought an old jeep, and began a series of journeys to the “un-Western” countries that attract her. Her book Amen: Grassroots Soccer (2010) is a stunning portfolio of young footballers—from 10 countries in southern and western Africa—who make balls and goals from whatever comes to hand and play because they need to.

Jessica Hilltout, Happy Soko FC, Malawi (2010)

Photo: Jessica Hiltout

Felipe Barbosa, Green Field (2012)

The Brazilian artist Felipe Barbosa takes everyday objects and recycles, reconfigures, and deconstructs them, thereby questioning their cultural significance. His 3-D walls of flattened and stitched-together soccer balls are spectacular—and, to some eyes, sacrilegious.

Felipe Barbosa, Green Field (2012)

Photo: Felix Barbosa/Cheryl Hazan Contemporary Art.