Every day, an average of 750,000 people pass through New York’s Grand Central Terminal (make sure not to inadvertently call it Grand Central Station, which is the name of the subway station below the train terminal). With that number ballooning to upwards of 1 million a day during the holidays, the terminal is one of the most-visited sites in the city, second only to Times Square.

Designed and built between 1903 and 1913, the building was constructed in the Beaux-Arts style, and heavily influenced by 1870s French architecture. The site was previously home to a train depot, built in 1871 by railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt who wanted to create a 42nd Street juncture for multiple train lines. By the turn of the 20th century, however, plans for a new station were underway, one that could accommodate electrified trains and relieve train and platform congestion,

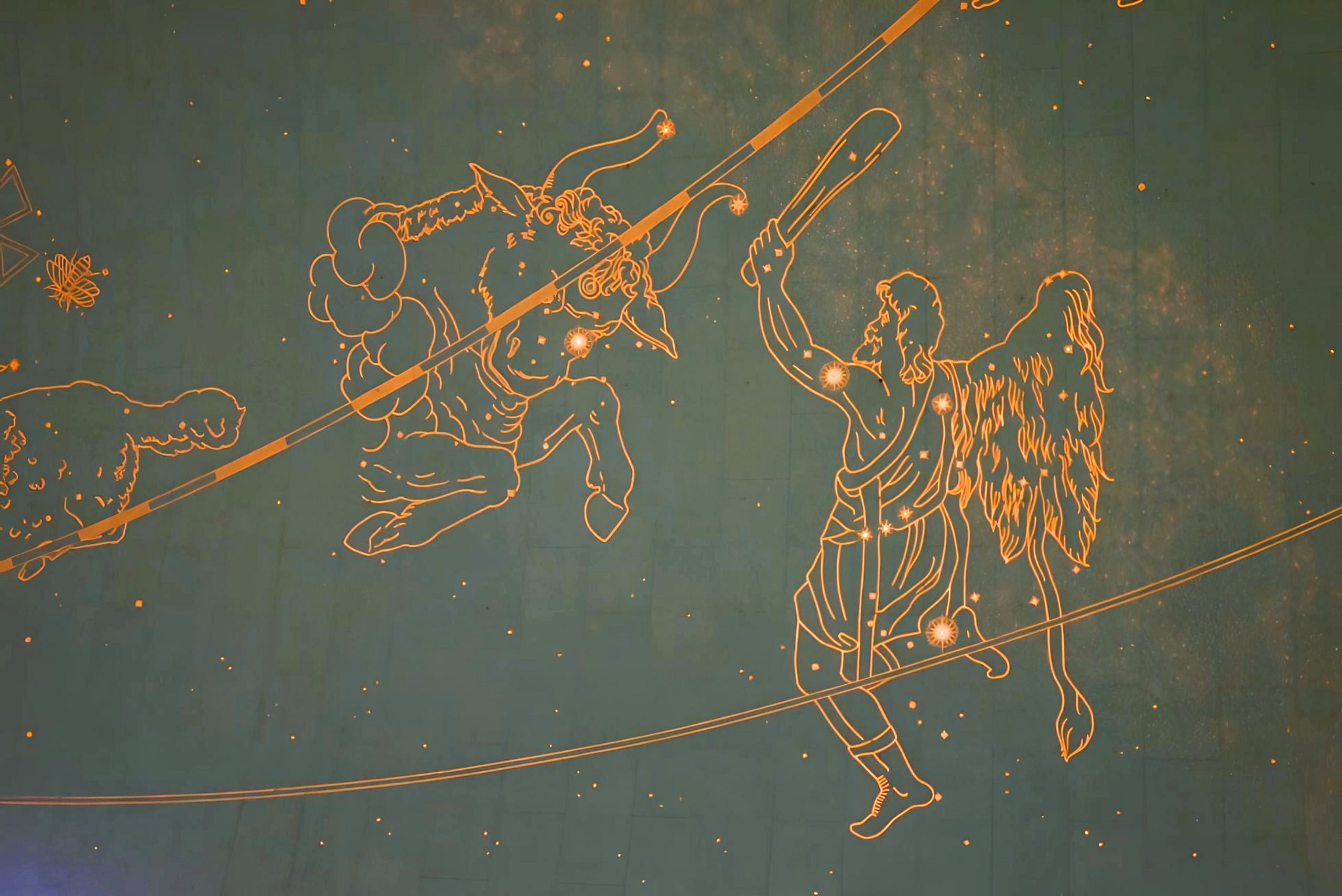

At the time of its completion in 1913, the terminal’s Main Concourse was the largest enclosed space in the world, measuring 275 feet long and 120 feet wide. What truly captivated the public, however, was the 125-foot-high vaulted ceiling, which was painted a distinctive shade of turquoise and covered in gilded illustrations of the zodiac and other constellations. Lights were even embedded in the more significant stars so that the ceiling seemed to twinkle like the night sky. Millions of people from around the world—alongside everyday commuters—have gazed up at this celestial ceiling since its completion, which has become as much an icon of Grand Central Terminal as of New York City itself.

We took a closer look at the ceiling’s mural and its history and found three intriguing facts that you should know.

Main Concourse, Grand Central Terminal, New York City. Photo: A. Olsen.

The Orientation of the Constellations Isn’t Quite Right…

Johann Bayer’s 1603 publication Uranometria, an atlas of the stars, served as the primary source of stylistic and compositional inspiration for Grand Central Terminal’s Main Concourse ceiling mural. Though the Uranometria is scientifically correct, and several astronomers were consulted for the overall design, there are somewhat baffling inaccuracies that can be observed in the mural’s overall design.

Foremost, the arrangement of the constellations is shown in reverse order—wherein east is west and west is east—except for the depiction of the Orion constellation. One early explanation for this from officials is that it was from God’s perspective, in other words, from “outside” the celestial sphere looking in, as if onto a globe. Unfortunately, this doesn’t quite solve the issue, as that would still leave Orion backward.

Souvenir postcards produced around the time of the terminal’s opening offer another explanation. The postcard features the ceiling but is shown astronomically accurately, leading some to speculate that the issue arose from those producing the work referring to a draft or sketch placed on the floor and projected upward, reversing the image. Perhaps the error was observed before the completion of Orion, but, ultimately, we can only speculate as to how or why the vast mural was composed in the way that it is.

One thing to note, however, is that some are a bit touchy about the subject, and don’t particularly care for the error being repeatedly pointed out. Astronomy writer and instructor George Lovie once rejoined, “Leave it alone. Its flaws are part of its fascination, as with the Leaning Tower of Pisa.”

Main concourse, Grand Central Terminal, New York City (ca. 1913). Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The Ceiling You See Today is Not the Original

A decade after the original Main Concourse ceiling mural was completed, it was already showing advanced signs of deterioration. A water leak in the roof caused mold and mildew to bloom across its surface, and a grungy coating from smog, soot, and exhaust smoke obscured the composition and the hallmark turquoise color. (Several sources have claimed that much of the grimy buildup was from cigarette smoke and nicotine, but this has been refuted by John Canning Company, which undertook a later restoration) Continuing to deteriorate, by the early 1940s the mural by many accounts was barely discernible, and the vivid shade of blue-green it is known for was instead more a beige tan with splotches of navy. Gross.

Rather than clean or redo the terminal’s ceiling, four-by-eight boards comprised of asbestos and cement were installed over top of the mural, and a reproduction of the work was painted. The outline of these boards can be seen today when looking closely. The newly painted ceiling, however, endured similar soot and smog build-up over the following decades, and another restoration project was undertaken in the 1990s. The removal of the overlain boards was considered, but Beyer Blinder Belle, the firm leading the restoration, found the underlying mural to be beyond recovery and deemed the removal of the asbestos-filled boards too hazardous. Thus, the boards were painstakingly cleaned and partially repainted (though very little, less than 1 quart of paint was used according to John Canning Company).

Detail of the ceiling mural in the Main Concourse of Grand Central Terminal, New York City. Photo: A. Olsen.

Historical “Easter Eggs” Are Hidden in Plain Sight

Though millions of people have passed under Grand Central Terminal’s iconic celestial ceiling, there are a couple of details that only hawkeyed observers might notice.

First of these, on the far corner of the ceiling, there is a small, dark, rectangular patch across the cornice and part of the ceiling. Many have ascribed its existence to being a cogent reminder left by restorers of the state the ceiling was once in—a sort of “before and after.”

Though the patch does in fact illustrate the level of pollution and filth that once covered the entirety of the mural, that is not its primary purpose. As one of the participating firms in the restoration, John Canning Company clarified that it is part of standard practice in conservation to preserve a material record of the prior condition of the project. By leaving this patch untouched, restorers and conservators in the future can reference and study this area to garner further information on the ceiling’s material history—and develop methods for further repair if and when needed.

Detail of the ceiling mural in the Main Concourse of Grand Central Terminal, New York City. Photo: A. Olsen.

And there’s one more point on the ceiling worth noting, a rather inconspicuous hole near the depiction of the constellation Pisces that is often missed or thought to be a star. The hole is where, in 1957, a wire was anchored in order to stabilize the installation of an American Redstone Rocket, which was installed for a period of time in the Main Concourse. The rocket was placed on view to help alleviate Red Scare sentiments and improve national confidence following the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik into low-earth orbit—the first satellite—the same year.