Throughout art history, the quest for remembrance and dominance has led to intense rivalries. Some of these have inspired feats of creative one-upmanship; some have been outright destructive. Either way, they have indelibly defined the stakes of art-making. Below, we list five of the most famous.

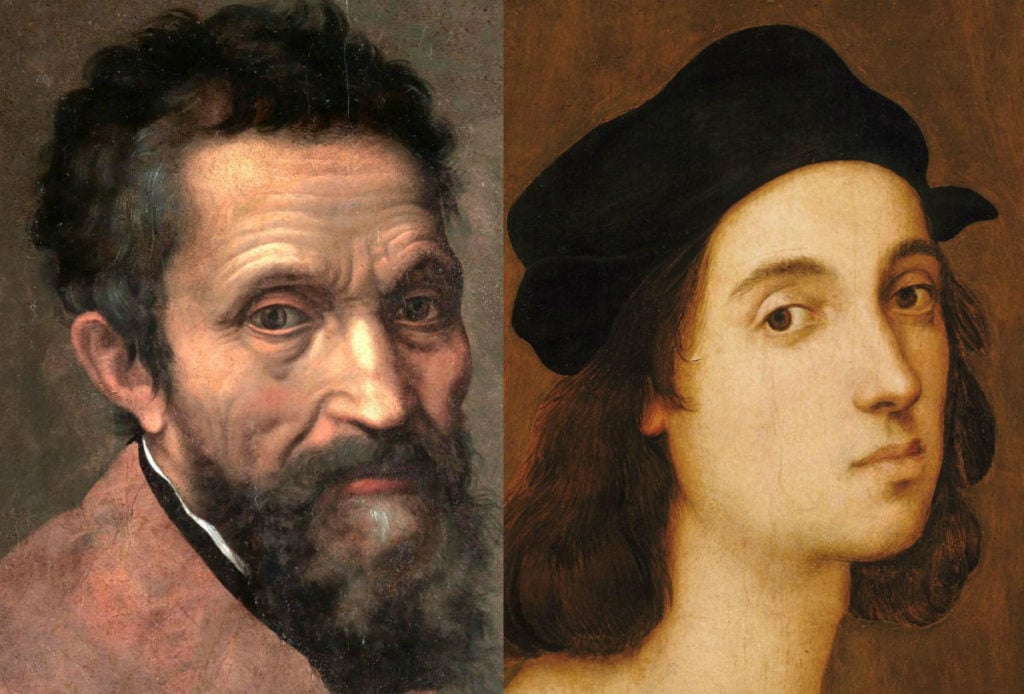

Raphael vs. Michelangelo

The youthful artist Raphael burst on the scene in Renaissance Italy in 1504 with an intricate style that was influenced by his predecessors Fra Bartolommeo, Leonardo, and Michelangelo. In 1508, at the age of 26, the young artist was invited by Pope Julius II to paint a fresco in the Pope’s private library in the Vatican Palace. Not only did he beat competitors such as Michelangelo and Leonardo to win the commission, his work gained rapturous reviews.

Even Renaissance chronicler Vasari, who basically viewed Michelangelo as a god and the high point of the Renaissance, acknowledged that Raphael gave the elder artist a run for his money:

Raphael of Urbino had risen into great credit as a painter, and his friends and adherents maintained that his works were more strictly in accordance with the rules of art than Michelangelo, affirming that they were graceful in coloring, of beautiful invention, admirable in expression, and of characteristic design; while those of Michelangelo, it was averred, had none of those qualities with the exception of the design. For these reasons, Raphael was judged, by those who thus opined, to be fully equal, if not superior, to Michelangelo in painting generally, and… decidedly superior to him regarding coloring in particular.

Michelangelo did not take well to the competition. As Robert S. Liebert writes in “Raphael, Michelangelo, Sebastiano: High Renaissance Rivalry,” he “made Raphael bear the brunt of his unrelenting envy, contempt, and anger.”

But Raphael could give as good as he got. For one thing, he famously painted Michelangelo’s features onto the figure of Heraclitus in The School of Athens.

Raphael painted a sulking Michelangelo as Heraclitus in The School of Athens (detail). Collection of the Vatican Museums.

Immortalizing one’s rival in the form of a pre-Socratic philosopher most famous for saying “you never step in the same river twice” might seem like a strange move, but Ross King clears up the meaning: “[I]t is not this philosophy of universal change that seems to have influenced Raphael to lend him the features of Michelangelo; more likely it was Heraclitus’s legendary sour temper and bitter scorn for all rivals.”

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Self-Portrait at the age of 79 years old (1859). Collection of the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Eugène Delacroix, Self-Portrait (ca. 1837). Collection of the Louvre Museum, Paris.

Ingres vs. Delacroix

The rivalry between the two titans of French painting unfolded amid a clash of styles in 19th-century France that saw the traditional neoclassical style favored by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres pitted against the avant-garde Romanticism championed by Eugene Delacroix.

The feud wasn’t just about artistic style; it was about the moral values ascribed to line and color, respectively. “Ingres was the self-appointed protector not only of linearism and classical tradition, but of morality and reason as well…,” writes Walter F. Friedlaender, the author of David to Delacroix. “[L]ine and linear abstraction embodied something moral, lawful, and universal, and every descent into the coloristic and irrational was a heresy and a moral aberration that must be strenuously combated.”

Thus, Delacroix, the most famous colorist, was viewed as not just artistically distinct, but a threat to the morality of French society. “I cannot look at Delacroix,” Ingres once said. “He smells of brimstone.”

Nor did the rivalry always stay in the realm of pure debate. Julian Barnes describes an encounter between the two rivals, who had been accidentally invited to the same party by a banker friend:

After much glowering, Ingres could no longer restrain himself. Cup of coffee in hand, he accosted his rival by a mantelpiece. ‘Sir!’ he declared, ‘Drawing means honesty! Drawing means honor!’ Becoming over-choleric in the face of the cool Delacroix, Ingres upset his coffee down his own shirt and waistcoat, then seized his hat and made for the door, where he turned and repeated, ‘Yes, sir! It is honor! It is honesty!’”

Clement Greenberg (1977). Photo by Kenn Bisio for the Denver Post via Getty Images. Harold Rosenberg. Photo by Maurice Berezov for A.E. Artworks, collection of the Jewish Museum, New York.

Greenberg vs. Rosenberg

These two giants of art criticism and the artists they advocated gave birth to the movement of American Abstract Expressionism and are associated with the US’s rise to artistic prominence. Greenberg gravitated toward the abstraction of Jackson Pollock; his rival, Rosenberg, favored the painting of Willem de Kooning.

Greenberg held strict formalist views, insisting that abstraction was a step in the progression of the tradition of painting, a claim rejected by Rosenberg, whose advocacy of what he termed “Action Painting” led him to proclaim that painting was no longer a picture, but the recording of an event. Anecdotes describe how the two men had to be kept separate at parties—but it was in print where their battle really played out.

Thus, in “How Art Writing Earns Its Bad Name,” Greenberg blasted critics like Rosenberg for “perversions and abortions of discourse: pseudo-description, pseudo-narrative, pseudo-exposition, pseudo-history, pseudo-philosophy, pseudo-psychology, and—worst of all—pseudo-poetry.”

Rosenberg clapped back with this sarcastic passage from “Action Painting: A Decade of Distortion”:

“[T]he will to remove contemporary painting and sculpture into the domain of art-as-art favors the ‘expert’ who purveys to the bewildered. ‘I fail to see anything essential in it [Action Painting],’ writes Clement Greenberg, a tipster on masterpieces, current and future, ‘that cannot be shown to have evolved [presumably through the germ cells in the paint] out of either Cubism or Impressionism, just as I fail to see anything essential in Cubism or Impressionism whose development could not be traced back to Giotto and Masaccio and Giorgione and Titian.’ In this burlesque of art history, artists vanish, and paintings spring from one another with the help of no other generating principle than whatever ‘law of development’ the critic happens to have on hand.

Brutal.

Matisse and Picasso’s rivalry resulted in some of the artists’ best work. Photo by Ralph Gatti, George Stroud/Getty Images.

Matisse vs. Picasso

Though the rivalry between Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso remained on the whole respectful and cordial, the two artists relentlessly spurred each other on creatively. In his book The Art of Rivalry, critic Sebastian Smee describes the competition between the two greats as “a drama unlike any in the story of modern art.”

In his 20s, the relentlessly ambitious Picasso squared off with Matisse, 12 years his senior, unleashing an extraordinary period of growth for both artists. According to Smee, Matisse’s iconic Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra (1907) “forced Picasso to radically rethink what he was doing,” and shaped the creative impetus on what would become Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), one of the Spaniard’s greatest works. When Matisse saw the latter, he lauded the younger Picasso as “an electrifying innovator,” and acknowledged he was a painter to “possibly learn from.”

It’s been argued, though, the status of this classic modernist rivalry, which has sustained scholarship and exhibition-making ever since, was a bit of a PR invention of the poet and avant-garde booster Apollinaire, who wrote a press release for a “Matisse/Picasso” show at Paul Guillaume’s gallery in 1918. To drum up enthusiasm, he depicted the show as a clash of the titans, and the rivalry of Matisse and Picasso as all that mattered for art-lovers, describing them as “the two most famous representatives of the two grand opposing tendencies in great contemporary art.”

Van Gogh vs. Gauguin

Vincent van Gogh, Self Portrait With Bandaged Ear (1889), detail. Collection of the Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust). Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake (1889). Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin’s rivalry began as a friendship. Van Gogh invited Gauguin to join him in the south of France where he was trying to establish an artist’s commune in the town of Arles. For a brief period, the Post-Impressionist masters fruitfully lived, worked, and collaborated alongside one another in the so-called Yellow House, resulting in a competitive but friendly artistic rivalry from which both benefited.

However, the arrangement soured. Both men were difficult characters. Van Gogh was plagued by mental instability, while Gauguin had a reputation for being a narcissistic and unpleasant person. When Gauguin depicted his friend in The Painter of Sunflowers, van Gogh is said to have recoiled, saying, “It’s me, but it’s me gone mad.” Not exactly helping his case, in a café afterwards, van Gogh hurled a glass of absinthe at Gauguin’s head.

Paul Gauguin, The Painter of Sunflowers (Portrait of Vincent van Gogh), 1888. Collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

According to legend, the Dutch painter cut off his ear after a row with Gauguin in 1888, giving the bloody ear to a stunned prostitute at a nearby brothel. Yet, so heated did their relationship become that recently some German art historians have put forward an alternate theory of the ear amputation, in the book In Van Gogh’s Ear: Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence. One of the historians, Hans Kaufmann, narrated the supposed actual scene to the Guardian:

Near the brothel, about 300 metres from the Yellow House, there was a final encounter between them: Vincent might have attacked him, Gauguin wanted to defend himself and to get rid of this ‘madman’. He drew his weapon, made some movement in the direction of Vincent and by that cut off his left ear.

Van Gogh experts generally stand by the story of self-mutilation. Kaufmann points to inconsistencies in the two artists’ stories, and at a passage in one of Van Gogh’s letters to Theo that seems to indicate a brutal potential within their rivalry: “Luckily Gauguin… is not yet armed with machine guns and other dangerous war weapons.”