The New Yorker has a long—and we mean really long—profile of Liu Yiqian, one of China’s richest men. He also happens to be a flamboyant art collector and museum builder whose antics have drawn both praise and consternation from observers and art experts.

Liu Yiqian drinks from his $36.3 million Meiyintang chicken cup.

Photo: courtesy Sotheby’s.

While adding nothing new to our knowledge of which works Liu owns, writer Jiayang Fan still manages to provide an exhaustive account of his his life—from his impoverished childhood and family hardships to his fortune building, collecting, and current everyday activities (he seems to be “less guarded” on WeChat than he is with the reporter). The article also deals with Liu’s quirks—such as chain smoking, dressing casually, and sometimes remaining anonymous at his own openings.

Fan also provides much-needed detail and context about the art scene in China, whether its the taste of its collectors or the history of its museums and the display of its art.

As is widely known in art world circles—and reported on by artnet News—Liu was behind many pricey, headline-grabbing sales including: a rare porcelain “chicken cup” from the Chengua period at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April 2015 for $36 million; the second most expensive artwork ever sold at auction, Amedeo Modigliani’s Nu couche (1918), which he bought at Christie’s New York for $170.4 million last November (the most expensive Chinese painting ever sold outside of China); a 600-year-old album of Buddhist art and calligraphy at Sotheby’s New York in March 2015 for $14 million (soaring past the estimate of $150,000); and an embroidered silk Tibetan thangka (15th century) for $45 million at Christie’s Hong Kong in November.

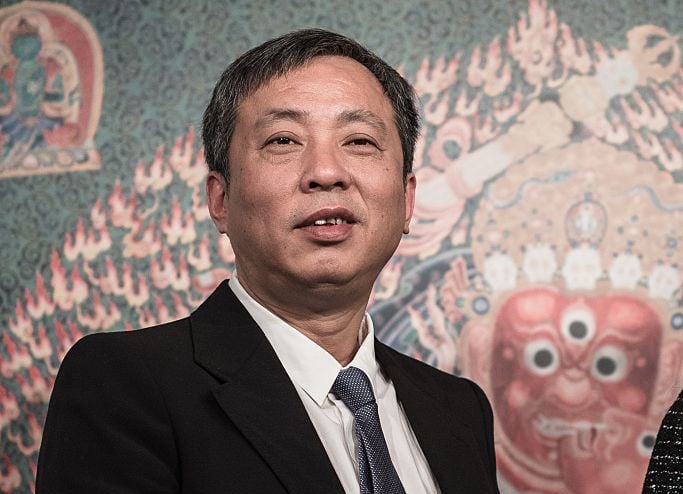

Liu Yiqian at Art Basel, where he bought a 36-foot painting by Gerhard Richter. Photo: Liu Yiqian via WeChat.

Liu and his wife, Wang Wei, run two private art institutions, the Long Museum (East and West). Among the more colorful highlights of the story are the following:

- Liu gets details of Modigliani’s life backward despite having dropped $170.4 million on his work. “It’s not just his art but his life. Every object has its story. Maybe if he hadn’t flung himself out of a window at thirty-six, his work wouldn’t be anywhere in the millions.” In fact, as is widely known, Modigliani died at age 35 of tuberculosis. His distraught widow Jeanne Hébuterne committed suicide the very next day by throwing herself out of a window in Paris.

- In 2015, in a hotel suite in New York, Liu celebrated his $5 million purchase of a 12th-century Tibetan bronze of a seated yogi by “stripping down to his underwear, mimicking the statue’s lotus pose, and circulating pictures of the yogi and himself on social media.”

- Liu began collecting as early as 1993, but he first drew notice in 2009, when he paid more than $11 million for a wooden Qing-dynasty throne carved with dragons.

- Liu tells the writer: “If a Westerner bought these Western masterpieces, people would think it was very normal. But…they were bought by an Asian, and not just a Japanese but a Chinese person. After all, isn’t that why you are here?” he asks as he looks at her with “eyes full of impish pride.”

- The writer also interviews Shanghai gallerist Leo Xu, who tells her about the gallery scene and its collectors: Francis Bacon, for instance, doesn’t sell. “The Chinese don’t see themselves in the work. Chinese collectors need to be able to relate to it and to feel that it has at least a little relevance to how they live or what they know,” Xu tells her. They prefer either traditional Chinese ink paintings or works by current art-world stars such as Antony Gormley, Damien Hirst, and Olafur Eliasson. Name recognition is paramount. “If buyers are putting down such a large sum, they want blue-chip artists, someone everyone knows,” Xu says.

- Liu’s unconventional approach to museum management and security is troubling to many people in the art world. A former auctioneer, Jia Wei, tells the writer that Liu and his wife don’t spring for security because they think it’s “unnecessary.” And Guggenheim Museum head of Asian art Alexandra Munroe has expressed shock by what she has observed on several visits to the Long Museum, telling Fan, “They are lacking in the absolute fundamentals of how to handle art.” She describes their improper display of scrolls as the “equivalent of walking into a museum here and seeing a van Gogh hung upside down. . .It’s about custodianship. Just because you own the art and the museum doesn’t mean that you get to disrespect it.”