Italian artist and writer Emilio Isgrò published his first collection of poetry, Fiere del Sud, in 1956, but his first engagement with texts as a basis for visual art was not until 1964, when he began erasing words from encyclopedias and other general information books. These early erased-word artworks, termed cancellature, were a synthesis of visual poetry and Conceptual art—which together formed a new genre of art of which Isgrò is considered a pioneer.

Over the course of his career, Isgrò has published numerous books, both poetry and fiction, and his practice of making cancellature has evolved to include redacting text from canonical pieces of literature like Shakespeare to more unconventional textual supports like regional and world maps. Isgrò has now been creating cancellature for over 50 years, and works dating from across the artist’s oeuvre are the subject of the current exhibition at Tornabuoni Art, Paris, “Emilio Isgrò: Erasing to Unveil,” which is on view through December 23, 2022.

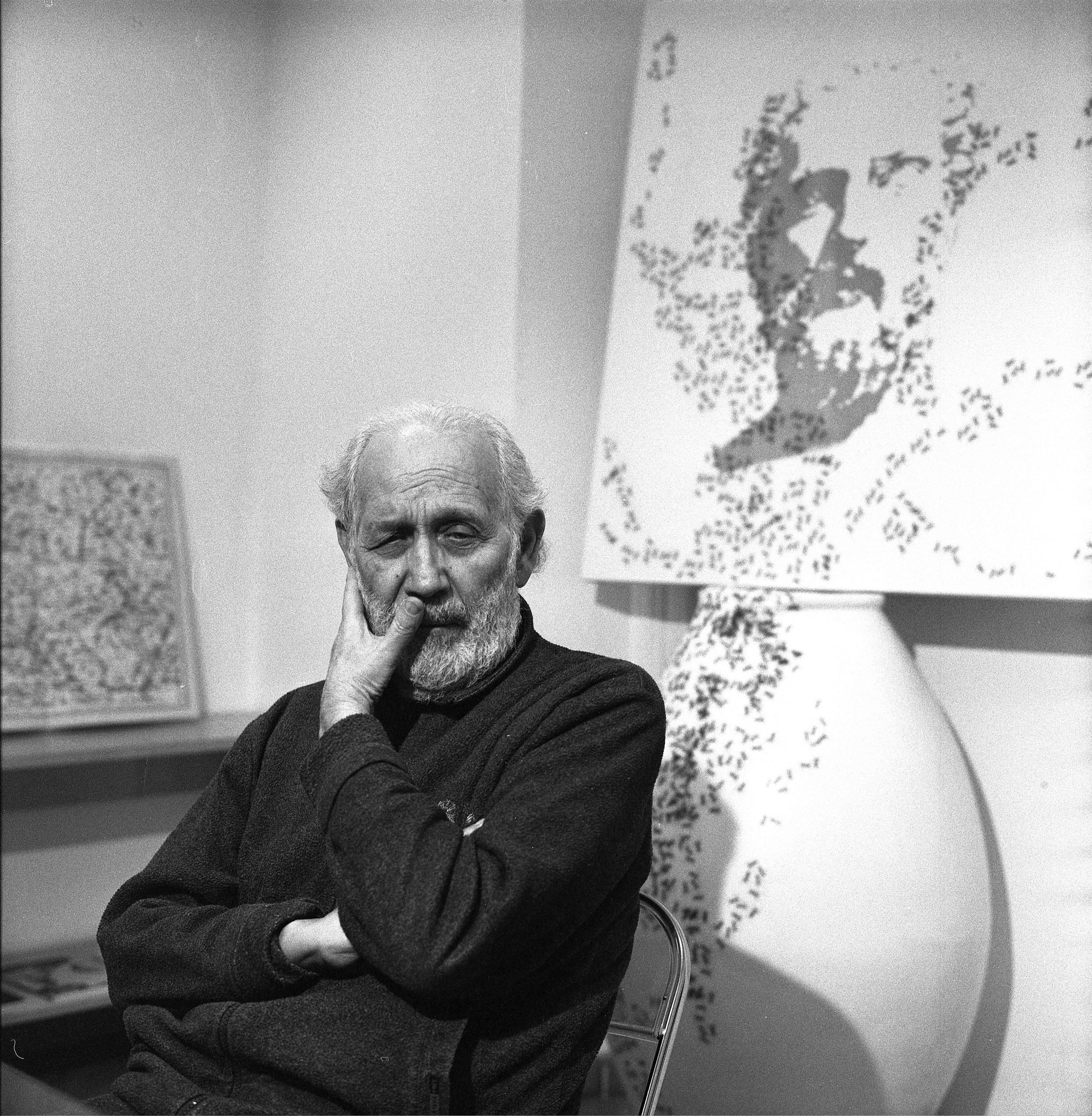

We reached out to Isgrò to learn more about the origins of the cancellature and how both the literary and art worlds have influenced his work.

Emilio Isgrò, Giotto (2014). Courtesy of Tornabuoni Art, Paris.

You made your first cancellature in 1964. What inspired and led up to the creation of it?

The cancellatura stem from a long reflection on the fate of the human language in a world where visual communication seems to prevail. Back then, in the early 1960s, it was Pop art that frightened me—not because it was not an interesting proposition, but precisely because it was too much so.

What would have happened if Pop and other similar proposals had extended the experiment to the whole planet? What would have become of the monotheistic religions of the Mediterranean, for which God coincides with the Word? And would the Aristotelian and Platonic philosophies that sprang precisely from dialogical thinking have endured?

So I began to erase words from books—not to destroy them, but to preserve them like the scrolls of the law in the Holy Ark or the Christian host in the tabernacles. Nor could I forget that the God who is hidden from Moses’s eyes behind the burning bush is a God who erases himself. This is the philosophical-emotional push of cancellatura. After the first push, however, the erasure could not remain the same. I had begun as a poet, and Pier Paolo Pasolini himself spent a flattering judgment on my first book of poems. On the other hand, if I wanted to fight a purely visual civilization, I had to learn to use the same tools as the civilization I wanted to fight.

The cancellatura are made using a wide variety of supports, from literary classics to maps and globes. Can you tell us a little bit about your artistic process—where do you start? What is the most important tool in your studio?

In the early days, all I needed was a felt-tip pen, or simply a bit of Indian ink with the classic double-zero brush, to make entire encyclopedias such as Britannica or the Treccani disappear. Then, with time, the tools were refined—also because a conceptual departure that remains static for decades is purely ideological and commercial, and therefore ineffective. In short, I had to become a painter like the others, but with a secret that the others did not possess: the “mental” approach that Leonardo da Vinci suggested to painters who were too bewitched by the easiest suggestions.

Installation view, “Emilio Isgrò: Erasing to Unveil” (2022), at Tornabuoni Art, Paris.

The exhibition at Tornabuoni Art presents a range of cancellatura works and series dating from over half a century. Are there any specific ideas or themes you want viewers to engage with?

I have nothing to ask of the public—because by now it is the public that asks me, quickly retracing the cognitive experience I have had over more than 50 years. The public has basically understood that my work is not a nihilistic or destructive experience (as is “cancel culture,” for example) but an attempt to reopen the doors of language by pretending to close them. Because in fact men no longer speak to each other, or speak in slogans and clichés, and it is precisely this that triggers wars and conflicts. Francis Fukuyama’s assertion that history ended with the defeat of communism was in truth somewhat premature, because it was with that defeat that history resumed its not-always-serene natural course. Today, we Europeans are reminded of this by the tragedy in Ukraine.

I read a quote in which you described the process of erasing or blotting out a word as “setting it free.” Can you explain this idea to us? Would the converse be that visible words are somehow trapped?

Yes, I want to say just that: words are prisoners of social prejudices. Too visible, too shouted by a planetary ruling class not always in keeping with the times. And on the other hand, it is not easy to assess the real weight of words when they are thrown around on the internet, where one does not really know where they start from, let alone where they arrive. Erasing them, after all, is an ecologically significant depolluting operation.

As well as being a visual artist, you are also an experienced writer. Does your approach to one inspire or influence the other, or do you view them as part of the same artistic whole?

For me it is always the same discourse deployed with different means and instruments each time. This is how it was from the Renaissance to Romanticism and the avant-garde. We must not forget that Michelangelo wrote sonnets (perhaps the most beautiful of the 16th century) and that the word ‘Cubism’ was coined by Apollinaire, while Boccioni would not have existed without Marinetti and Dada without Tristan Tzara—all the way to Surrealism, which, thanks to the writer André Breton, paved the way for René Magritte and Max Ernst. In short, the art of the last hundred years also comes from literature. And today, it is clear for all to see that the issue of words is so dramatic that, in addition to the usual poets and novelists, visual artists such as Anselm Kiefer, Barbara Kruger, and Jenny Holzer have thrown themselves at its rescue. Of course, the ground had been prepared in their time by concrete poetry and visual poetry, but eventually even the most classical painters realized that language could restore to art the profound depths lost with the invention of photography, replacing the old Renaissance perspective with an unprecedented “verbal perspective.”

I consider it fortunate to have been able to play on so many dissimilar tables: because it is the capitalist “specialization” of labor that has rendered painting useless, laden with effects but devoid of affections, only corroborated by itself and by nothing else. This is good for decorating the world, but certainly not for knowing and reconstructing it.

Emilio Isgrò, Othello (2019). Courtesy of Tornabuoni Art, Paris.

Are there any artists, either historical or contemporary, that have influenced your work?

The list of what did not influence me would be shorter. My earliest interests were mainly in literature, music, philosophy, and a little in science. I had little or no interest in painting in the canonical sense, apart from the exercises my painter uncle had me do as a boy in Sicily. I invented a canon myself, with the cancellatura, until I discovered that this canon coincided perfectly with the canon of painting itself. So much so that when my painter friends thanked me for teaching them to paint by erasing, I was a bit incredulous. And I eventually accepted being considered a painter like any other. But I was already 80 years old. Too late to ruin my hands, and especially my head.

What’s next? Are there any themes or supports you would like to engage with or explore that you haven’t yet? Or new projects you may have already started?

Nowadays, others make projects for me. If they interest me, I make them my own. Otherwise, I let them go. No artist can live in complete solitude. And I today have the privilege of being less alone than I was 50 or 30 years ago. It is no disgrace to work for those who love you.

“Emilio Isgrò: Erasing to Unveil” is on view at Tornabuoni Art, Paris, through December 23, 2022.