Lia Rumma has lived the storied career most young gallerists dream about. Rumma, who made her name championing the likes of Joseph Kosuth and Enrico Castellani, got her start in the 1960s—not as a dealer, but as a collector. Alongside her husband Marcello Rumma, the couple was among a cohort of intrepid young Italian collectors interested in radical forms of postwar expression. Together, and through their lens as collectors, the Rummas began organizing events to support a new generation of artists.

In 1968, her husband Marcello helped organize the famed “Arte Povera + Azioni Povere” exhibition curated by Germano Celant, which heralded the arrival of the Arte Povera movement on the global scene. After Marcello’s death, Lia Rumma opened her first gallery in Naples in 1971; 20 years later, she added a space in Milan.

In 2021, Galleria Lia Rumma celebrated its 50th anniversary. This year the gallery will be presenting Gian Maria Tosatti at the Venice Biennale—the first time that the Italian Pavillon is represented by just one artist.

Ahead of the Biennale, we spoke with Rumma about her career, the artworks she didn’t want to part with, and the lessons she’s learned.

Can you tell me about how you first became interested in the arts and why you decided to found a gallery? I know you had founded a publishing imprint with your husband Marcello, and then the gallery in 1971.

My interest in contemporary art began in the 1960s and is undoubtedly linked to my husband Marcello Rumma: it was together that we began to be passionate about what was happening in art at the time. We traveled a lot in Italy and Europe, we met the great gallerists of the time—Ileana Sonnabend, Leo Castelli, Plinio De Martiis, Gian Enzo Sperone, Fabio Sargentini, etc.—and we built our own collection.

In those years with Marcello, we intersected with a new generation of artists and decided to promote them as protagonists in a series of art exhibitions at the ancient arsenals of Amalfi. Among these, we must certainly remember the 1968 exhibition that marked the birth of Arte Povera at an international level, “Arte Povera + Azioni Povere,” curated by Germano Celant, today considered one of the most important exhibitions of the century.

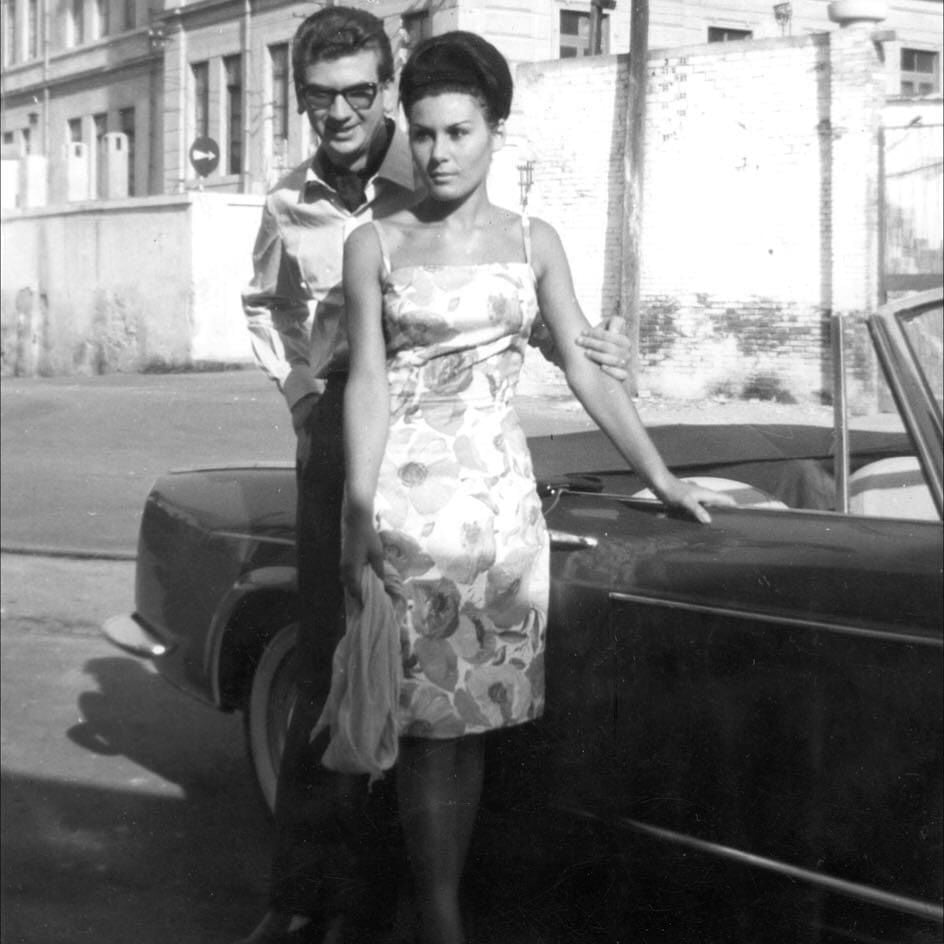

Lia Rumma in Amalfi. Courtesy Archivio Lia Incutti Rumma.

In 1969 Marcello founded the publishing house Rumma Editore, with which he published fundamental texts on aesthetics, philosophy, and art. I took charge of the collection. When Marcello died in 1970, I decided to start a new path: that of a gallerist. In 1971, in a small garage in Parco Margherita in Naples, I opened my first contemporary art gallery with the exhibition “The Eighth Investigation (A.A.I.A.I.)” by Joseph Kosuth.

What have been the biggest lessons you’ve learned in 50 years running a gallery? What piece of advice would you give to your younger self?

Being a young gallerist of contemporary art in Naples in the early 1970s was not easy! I can, however, say that I have always had the “obstinacy” to believe in my choices and in my ideas. This is the lesson I would give to my younger self.

Lia Rumma and Gian Maria Tosatti at the retrospective “Seven Seasons of the Spirit,” curated by Eugenio Viola at Madre Museum, Naples (2016—2017). Courtesy of Lia Rumma Gallery, Milan/Naples.

Were there any works that were particularly hard to part with over the decades?

I will make a confession: often, and to the despair of my staff, I have blown more than one sale in order not to part with a work! You see, as I told you, even before being a gallery owner, I was a collector. That immediate affection that one feels towards a work, that desire to consider it as part of one’s own collection has never abandoned me—even if now I am, so to speak, on the other side of the fence!

Do you have any favorite shows from these past five decades? Proudest moments or regrets?

In 50 years of activity…you win and you lose! You lose and you win! Moments of regret for unrealized exhibitions are a sore point, but there are also many moments of pride in exhibitions that leave an indelible mark on the history of art. From Anselm Kiefer’s permanent installation The Seven Heavenly Palaces (2004–15) at the Hangar Bicocca in Milan, to shows by Gino De Dominicis, Joseph Kosuth, and William Kentridge at the Capodimonte Museum, to the great exhibition dedicated to the story of my husband Marcello Rumma at the Madre Museum in Naples in 2020….just to name a few from the last two decades.

Installation view of Gian Maria Tosatti’s “Seven Seasons of the Spirit, 7. Land of the last heaven” at the former Trinità delle Monache, Naples, 2016. Courtesy Lia Rumma Gallery, Milan/Naples.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

Undoubtedly, the relationship with artists has been fundamental for me. It’s a perpetual journey of knowledge and experience.

If you were not an art dealer what would you be doing?

Unfortunately, I don’t know how to do other work. But as a child, I dreamed of being an actress.

Gian Maria Tosatti will be the only artist presenting in the Italian Pavillon at the upcoming Venice Biennale. Can you tell us more about his plans or what we might be able to expect?

I prefer Tosatti to speak directly about his projects. His works—large and articulated environmental installations—are not simply works, they are stories, investigations into the most intimate fabric of society.

For his installations, the artist usually chooses places on the outskirts of cities, places torn apart by social injustice and environmental disasters. Just think of the “Odessa Episode,” the fourth chapter of the project My Heart Is a Void, the Void Is a Mirror, started by the artist in 2018 in the city of Catania and then continued in Riga, Cape Town, Odessa, and Istanbul. The images as dramatic as they are enchanting or disarming! So, Gian Maria Tosatti at the Biennale? That’s quite a challenge!

Do you have any predictions for the future of the art market? Any trends or ideas you’re finding particularly compelling now?

Why not ask the Sibyl?